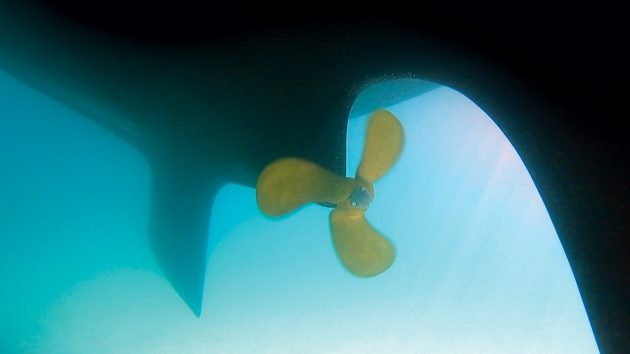

A change of boat propeller can dramatically improve a yacht’s performance while saving money on fuel. Sam Fortescue reports on the latest options

A well-known truism of boat ownership is that sailing with a fixed propeller is akin to towing a bucket astern. We all know that a feathering or folding propeller has huge advantages under sail, but what are the costs of motoring with a sub-optimal propeller? Even purists will use the engine to manoeuvre in and out of busy harbours, and most of us are willing to fill in with horsepower when the wind drops.

You won’t be surprised to hear that propeller manufacturers believe that sailors often have the wrong screw fitted. And if that delicate balance between the propeller size, engine power and the boat’s speed potential don’t align, you’ll be losing money to inefficient performance under power.

‘It’s pretty common that props aren’t the right size,’ explains David Sheppard, managing director of Bruntons, maker of the Autoprop. ‘The usual first sign is that the engine is being overloaded or underloaded. If it doesn’t reach its full rpm, then it’s overloaded. And if it’s underpropped, you’ll get revs above the rated rpm. It’s more difficult to tell with modern diesels, but in the old days, you’d get black smoke coming out of the back because there’d be too much diesel going in and the engine wouldn’t be able to turn fast enough to burn it.’

There are some reasons why you might want to be overpropped, but engine manufacturers will often void the warranty if the propeller is incorrectly sized. Worse still, you’ll be putting additional wear and tear on the engine which will result in a shorter service life and greater maintenance. With labour rates of £50-80/hr, even minor repairs can cost hundreds of pounds, with any new parts taking it into the thousands.

Check that you have a viable engine-to-prop gear ratio. Note that additional blades can be used where there isn’t sufficient space for a larger diameter prop, as on this four-bladed Maxprop. Photo: Jack Patton

Prop mismatch

A mismatch between engine and prop often creeps in when a boat is repowered. ‘We usually get customers ringing up after their boat’s been re-engined,’ explains Chris Hares of Darglow Engineering, which manufactures the FeatherStream propeller. ‘If you just take out an old 30hp engine and replace it, you can end up with a different gear ratio that requires a different propeller.’

For many cruising boats with faster turning engines, a 2.6:1 gear ratio gives the best balance between prop diameter and speed. A low 2:1 ratio means a higher propeller speed and therefore a smaller diameter. The opposite is also true. There is a lively trade in 10-year-old Bukh DV20/24 lifeboat engines, which have to be replaced by law but have seen little use. They use a high 3:1 reduction ratio which requires a bigger-than-average propeller, and most sailing boats simply don’t have the space for it.

‘People can spend £9,000 repowering the boat and then find it performs worse than it did beforehand because it’s got a higher shaft speed and isn’t efficient,’ says Hares.

And don’t think that new boats are immune to this problem, either. When Yanmar replaced its popular 3YM30 with the 3YM30AE, it took time for some boatbuilders to notice the max revs had been cut from 3,600 to 3,200.

‘Designers usually know what they’re doing, but what goes wrong is when the supply of engines or gearboxes changes and nobody connects the dots,’ Hares says. ‘We saw it a lot during Covid because of the supply problems.’ Ideally, you want the engine to hit its rated rpm with the throttle fully open, and it is simple enough to test. ‘You need to take the boat out on a fine day before it gets covered in barnacles and going full throttle,’ says Hares.

An Autoprop consumes a third less diesel than a fixed propeller

Money savings

If you’ve established that your engine and propeller combination isn’t giving you the performance it should, or if you’ve decided it’s time to invest in a feathering or folding prop to increase your sailing speeds and reduce passage times, what next? Well, working out a budget is a good first step.

Feathering props are on average 20 per cent more expensive than folders, if you overlook the good-value Kiwiprop. This alone might be enough to steer you one way or another.

Set against this is the efficiency of the propeller itself under power. Trials by French sailing magazine Voiles offer a good insight. In tests with a 34ft Jeanneau using a 29hp Volvo engine with a top rpm of 3,600, the Autoprop, Gori and Flexfold all outperformed a fixed prop.

The Autoprop consumes a full one-third of a litre less diesel per hour to maintain six knots of boat speed – a saving of around 50p/hour at current pump prices. The difference between the Autoprop and the worst performing feathering propeller was starker still – nearly one litre per hour.

But perhaps more striking than the potential fuel savings is the gain in range. At six knots, the Autoprop could manage 42.5 miles on 10 litres of diesel. The fixed prop gave 34.6 miles and the Maxprop managed just 27.2 miles.

The test was done in flat water conditions, but it illustrates the big differences in safety cushion offered by the different prop designs.

The most efficient pitch-to-diameter ratio is 2:3

What size boat propeller do you need?

Sailing boats should have large propellers, turning slowly with minimal slippage. However, there is limited space under the hull, so the smallest blade and least amount of drag, is best.

‘The most efficient pitch-to-diameter ratio is 2:3,’ explains Hare. ‘But it’s not always possible to do that because there isn’t always enough room to accommodate that diameter.’

Pitch is the distance the prop would travel forwards in a rotation through a soft solid. Thus, a 15in pitch means that the propeller blades are angled so they would advance 15in in a single rotation if there were no slip.

‘There’s an optimum diameter and pitch,’ adds Sheppard of Bruntons. ‘If you can’t fit that, you get a restricted-diameter prop, with greater pitch. The more you compensate, the less efficient the prop becomes. You don’t always notice it on a heavy sailboat, but it’s important because you get more prop walk due to the greater paddlewheel effect.’

Space below the hull limited prop diameter on this boat hence the five-bladed Maxprop, at the cost of additional drag

How many blades?

For engines below 100hp, you don’t need more than three blades. On saildrive yachts with plenty of hull clearance, it’s common to have a larger two-blader, which is efficient but subject to vibration. It’s essentially a case of having sufficient blade area to handle the horsepower. More blades means more drag, but when there isn’t space to fit the right size prop you might need an extra blade.

The Featherstream hybrid propeller with stainless steel blades and a bronze body

What’s the best material for a boat propeller?

We tend to think propellers should be made from honey-coloured bronze, but they are, in fact, usually made of a complex alloy involving copper and tin plus differing amounts of aluminium, nickel, manganese, zinc and iron, which results in a material with good corrosion resistance that’s easily machined.

Italian firm Ewol, however, builds beautiful, but expensive, feathering props from polished stainless-steel because it is less susceptible to galvanic corrosion from stray current while offering greater strength for a finer profile.

Seahawk, meanwhile, has less expensive stainless props with its Autostream and Slipstream cast in 316 and 2507 steel, while Darglow has developed a bronze body with stainless steel blades in a hybrid called the Featherstream.

Polished stainless-steel prop from Ewol. Note the bronze bushings to prevent steel-on-steel wear

‘All-bronze props will wear out quicker and need reconditioning sooner on the blade bearing surface, where it rubs against the hub,’ explains Hares. ‘But, it’s very difficult to have an all-stainless prop. You can’t run stainless steel on another piece of stainless as a bearing surface, where they catch each other and get stuck. So, you need a bronze bushing between blade and body, which tends to wear down quite fast.’

Composite propellers are a cheaper solution to the corrosion problem, with the best-known being the Kiwiprop, whose black Zytel blades are mounted on a stainless steel pin and never wear. They’re not the most efficient blades, due to their broad, flat profile, but they are the cheapest feathering option.

Flexofold also produces a folding two- and three-blade prop with a composite boss, which provides the same galvanic isolation.

Gori’s folding propeller can swivel to offer the leading edge in reverse

Folding vs feathering boat propellers

Compared with a fixed propeller, either option will offer massive improvements in hydrodynamic efficiency under sail. You can expect 10-20 per cent more boat speed in given wind conditions – at least half a knot and possibly more than one knot for bigger boats, enough to save an hour sailing a 40ft yacht from Dartmouth to Plymouth.

It’s harder to draw a distinction between the drag from a feathering propeller, such as the Autoprop or the Kiwiprop, and a folding prop.

‘Feathers have flat blades which reduces their efficiency a little, to perhaps 95% of a folding prop,’ says Hares at Darglow. ‘But most sailing boats have more than enough power in the engine, so you’re going to hit hull speed with any of these, but you’ll burn less fuel with a folding prop.’

The Flexofold feathering prop is having success with electric motors

Of more concern are the other variables around prop design, such as maintenance, performance astern, regeneration potential and noise/vibration. Folding props tend to be easier to maintain with fewer wearing parts and no annual greasing. They may also be more efficient motoring ahead. A feathering prop, meanwhile, will go much better astern.

With the exception of the Gori, folding props can’t swivel to offer the leading edge in reverse, which makes them just as inefficient as a fixed prop. Their design also means that the thrust they generate astern is trying to close the propeller, so, you need to give the engine higher revs, and that means more prop walk.

‘If you’re struggling with a fixed prop, that’s going to get worse with a folding prop. Feathering props are much better at stopping the boat and give less prop walk than folders as you can manoeuvre with a modest amount of throttle.”

SPW’s new Variprop GP has been specifically designed to offer efficient regeneration

Boat propellers for electric

There is no real difference between the dimensions of a prop for electric vs diesel operation if all other variables remain the same. However, the high torque often means electric systems have lower shaft speeds, which will require a bigger prop or an extra blade to increase power transmission.

‘If you’re putting in an electric motor, we specify a very slow shaft speed and a slow-turning prop because the torque is flat, which is good for a propeller,’ says Sheppard. ‘Otherwise, considerations are broadly the same.’ But because regeneration is so important in an electrical system, feathering props dominate. The hybrid folding-feathering Gori can regenerate, and Flexofold reports some success too, while the Kiwiprop and Seahawk’s Autostream are not suited.

Of the feathers, Bruntons has re-engineered its Autoprop specifically to increase regeneration potential. Called the Eco Star, it can produce 200W at five knots of sailing speed or 550W at seven knots. Ewol has also developed an expensive regen version of its three-bladed Orion called the EnergyMatic, and SPW’s new Variprop GP has been fine tuned for regeneration.

Oceanvolt’s award-winning HighPower ServoProp 25

Variable pitch boat propellers

Variable pitch propellers are commonly found on large ships, but Oceanvolt has developed a small-scale product for the cruising market as part of its electric propulsion package. Its ServoProp

is a unique feathering three-blader for saildrives, which can rotate more than 180 degrees to present the leading edge both forward and astern. But its clever electronics are all directed at a single purpose: generating power. Paired with an Oceanvolt electric motor, the ServoProp can be used to make electricity when the boat is under sail.

It adopts an optimal pitch for being dragged through the water to produce around three times as much power as a fixed-pitch propeller. The latest HighPower ServoProp 25, launched this year, has continuous pitch control for even better regeneration and more efficient motor sailing. Ideal if you’re looking to fill a big battery bank and give yourself near endless range.

Enjoyed reading this?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price, so you can save money compared to buying single issues.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

-

-

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

-

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.