A length of rope and a fender can turn tricky manoeuvres into a piece of cake. Tom Cunliffe explains springing on and off a dock

Springing on and off

In my youth I served as mate on a coastal merchant ship. She carried bulk cargo and was powered by a single screw. Working her in and out of one tricky berth after another was as much an everyday event as tucking in to the cook’s world-class breakfasts, yet neither the skipper nor our pilots ever called for a tug. They moved her around using the boat’s ropes. Subsequently, I’ve sailed on a number of large, well-run yachts, power and sail, and I’ve noticed that the same rules hold good. You can shove a 25-footer off a wall on a windy day most of the time, but sooner or later it blows so hard that you can’t. For a 40-footer, the crunch comes more often, and so on up the scale.

Working on the Expert on Board series, I meet a wide variety of yacht owners and charter operators. Lymington Yacht Charters specialises in substantial craft and I was talking recently with Arnie, the boss, about how his clients manage to handle them.

‘Generally not much problem at sea,’ he replied. ‘In harbour, it can be a different story.’

This rang true with my own experience, so I asked him if he’d mind lending us a big Jeanneau to talk through how to use spring lines. He was all for it and, as luck would have it, we turned up on a windy day. Thirty-five knots was on the clock at times and the boat weighed in at over ten tons. All we had for crew was yours truly and Miles, my diligent deckhand. We spat on our hands, rigged warps and b0at fenders, and squared away for a handy pontoon.

Terminology

Terminology is always a vexed area when it comes to spring lines. Throughout my own experience – yachting and merchant – the ‘stern spring’ is run forward from the stern and the ‘bow spring’ or ‘head spring’ is led aft from the bow. However, some authorities equally correctly refer to a ‘fore spring’ and a ‘back spring’. I have no quarrel with this, but for the purposes of this article we must adopt one convention or the other, so we’re going for ‘stern’ and ‘bow’.

What does a spring do?

A spring line is rigged from the bow or stern of the boat and led ashore towards amidships – aft from the bow or forward from the stern.

It has two effects. If led at a sufficiently narrow angle, it helps stop the boat from surging ahead and astern, but perhaps more importantly, it also works as a lever. If the boat tries to move astern against the stern spring it will force her stern in and her bow out. Vice-versa with a bow spring. This gives you a number of important options for manoeuvring as well as securing alongside. If you’re wondering about rigging spring lines from those cleats or fairleads you find amidships on many larger yachts today.

Springing on

Think ‘spring-line manoeuvres,’ and ten-to-one you’ll be conjuring up an image of a yacht springing herself off a tricky dock. Bigger vessels, however, often have as much difficulty getting close-in alongside as they do extricating themselves from a weather berth. Even in a smaller yacht, it can be a struggle trying to pull her in against a strong wind when you’ve managed to get a couple of lines ashore, but she’s drifted five yards back out again in the process. The soft option is to ask someone ashore to heave you in, but this is a bit of a liberty. Pulling her in from on board is often awkward because of the guardrails. You could grind her in if one line leads to a powerful winch, but the neatest answer is to spring her on.

The first time we brought the big Jeanneau alongside, we found ourselves in exactly that situation. The yacht ended up blowing off the dock with two lines of more or less equal length at right angles between us and the wall. To bring her in, we could either engage ahead or astern, whichever was most convenient (we tried both), and apply a few revs. As we built up power, the yacht started walking in against her lines. Going ahead, the bow line now became a bow spring. Vice-versa astern. She strolled in as easily as if she were one leg of a parallel ruler and the dock were the other. The connectors are, of course, the two lines. Once she was alongside, I kept the revs on just as my old skipper on the ship used to, while Miles ran out the other two lines that would keep her there. Then we shut down the power and that was the job. No grunting, no rushing around, no busted insides.

We’ve got bow and stern lines secured but the wind is blowing the yacht off and with her high topsides it would have been hard work to haul her in

Parbuckling

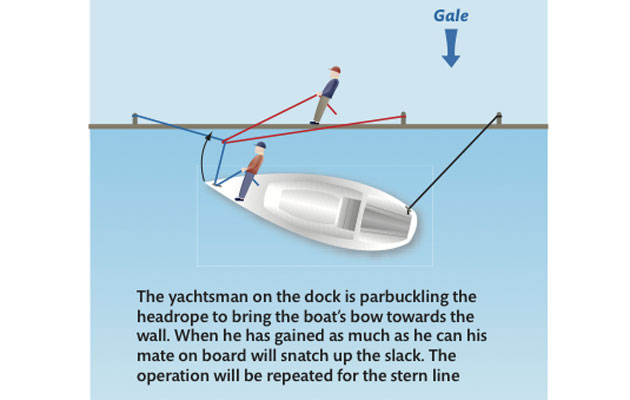

If it’s blowing a gale and there’s not enough room fore or aft to drive the boat in against her lines then try parbuckling. Attach a line to the dock so that when you lead it to the middle of the shore line it makes something like a right angle. Take it round the line, bring it back to where you started and heave. As you do, the dock line will take on an increasingly indented vee shape and the boat will walk smartly in alongside by the ancient principle of ‘parbuckling’. Once the fenders are touching, either run out a new dock line or let go the parbuckle and have your mate snap up the slack in the dock line like lightning.

The yachtsman on the dock is parbuckling the headrope to bring the boat’s bow towards the wall. When he has gained as much as he can his mate on board will snatch up the slack. The operation will be repeated for the stern line

Springing off

Having brought the boat alongside our very windy berth, the next job was to demonstrate the two classic springing operations. The truth is that because the wind was blowing us off, we could have just let go our lines and let her drift, but we were on a mission. Fortunately, the Jeanneau had so much displacement that she helped us by staying put. Had it been blowing a gale onto the dock, the theory and practice would have been just the same.

Springing off the stern

My first thought when I’m pinned onto a dock by the wind is to try and get the bow off so I can simply ‘drive out’ of the berth. In a modern yacht, however, this is often not the best answer because, left to her own devices with no way on in open water, she will probably end up lying with her stern closer to the wind than the bow. Her natural tendency is to weathercock with her transom to windward. This means it often proves easier to motor out of a weather berth stern first. The favoured option is therefore generally to spring the stern off the dock.

Clambering aboard over the high bow was going to be a no-chance situation, even for Miles, who’s an athletic sort of chap, so we rigged the bow spring as a slip rope. While we were at it, we also set a slip on the stern line because we were only two-handed and there wouldn’t be time for Miles to let the stern off then gallop up to the bow. If the boat really were being blown on hard, he could simply have let go the stern line from the dock, stepped on board and walked forward while I was springing her off. Finally, we set up fendering immediately abaft the stem.

I slipped the stern line and put the engine into slow ahead. I also steered ‘into’ the dock so that the prop-wash would help throw the stern out. Away she came. When the stern was far enough out to be certain there would be a result, I went into neutral, Miles slipped the spring, and away we went.

Climbing onto the bow of a departing yacht is high risk so we rigged slip lines and hung fenders from the pushpit

Tom slips the stern line, steers into the dock and motors forward against the bow spring. The fenders take the strain

When the stern is well clear, Tom engages neutral and gives the order for the bow spring to be slipped

Springing off the bow

This works exactly the same as springing the stern off, except that because the engine will be running astern, there will be no prop-wash effect on the rudder, so the spring line can’t be ‘power-assisted’. Bear in mind that forcing the bow upwind is typically not what the boat wants to do, so if it’s blowing like the clappers you’ll need to screw the head well out before letting go and leaving the berth. Make sure the stern is well fendered, let go the bow, and motor astern against the stern spring line.

To work properly, a stern spring needs to be led from the extreme corner of the boat. Because the stern deck is lower and more accessible than the bow and the boat is being blown hard onto the dock, you can generally dispense with a slip rope for this manoeuvre. On my boat, the crew just stands by ashore holding the spring on the cleat with a round turn, then when the springing is done and the bow is far enough out, I go into neutral, they whip the turn off and step on board as I’m engaging ahead to drive out. Less complication equals less to go wrong. On a boat with very high topsides, this won’t work so, unless some dockside matey offers his services, you’ve no choice but to rig a slip and make sure it doesn’t foul.

The stern spring runs from the stern to a cleat on the dock amidships. The spring and the bow line are both rigged as slip lines

Tom puts the engine in astern as the bow line is slipped. If the wind is blowing off the dock it may be sufficient just let the bow go and wait

Sugar scoops and bathing platforms can cause problems when springing the bow. It may be worth investing in an extra large fender

Tom takes her out of reverse, slips the stern spring and motors ahead. Always check that there are no lines near the propeller

Slip ropes

By their nature, spring-line manoeuvres are often chosen when things are somewhat fraught. That’s the time to run the line around the cleat on shore and back on board again, so that both ends are fast on the boat. When the time comes, let off the shorter end, pull it all through and you’re clear away without the danger of leaving some poor soul behind. Slip ropes can easily foul, however, and to be motoring away when a slipped bow spring nips its turn and comes tight is a sure formula for embarrass-ment. The bottom line is that slip ropes should only be used if they’re really necessary. When that time comes, take every step you can think of to ensure they run clean.

The midships cleat or fairlead

Neither serves any purpose in the sort of manoeuvres we’ve described so far in this article. It comes into its own in marinas where the finger pontoons are not long enough to set up bow and stern springs. Lines led to it from fore or aft certainly prevent the boat from surging, but they are far less effective than true springs for holding her parallel to the dock. Because the lead is so near the centre of the boat, the magic leverage of the spring line is simply not there.

Shorthanded docking with the midships cleat

If you get only get one line ashore, consider using the midships cleat and motoring against it. It may not be pretty but it will give you time

A modern yacht tends to be lozenge-shaped when viewed from above. It stands to reason that if she’s secured alongside by a single short line from amidships she will roll forward or aft around her fenders until the line comes tight. At that point, she’ll either stay where she is or rebound the other way. Sometimes, the equilibrium can be further stabilised by motoring slow ahead. Coming alongside short-handed therefore, all you need do in theory is secure this line. The boat will then remain more or less stable while you run out the permanent dock lines.

For the theory to work out in practice, the cleat or fairlead must either be dead on the boat’s static pivot point or slightly abaft it. If it’s forward of it, any attempt to motor ahead will throw her stern out and her bows in. Motoring astern won’t help much either. If the rope is tight enough enough, she may lie doggo with no power on at all, but making it up that short on a bigger boat is generally impracticable. I tried it on a long-keeled yacht a few months back and the pivot point was so far aft that we had to lead it direct from a cockpit winch! Nonetheless, I’ve seen couples working this system to great effect, so everyone should at least give it a go. Don’t be disappointed if it won’t work for you, however. Miles and I gave it our best shot on the Jeanneau. We tried it with longer ropes and ‘super-shorties’ that could never have been rigged in anger. We motored ahead and astern, then we shut down the power, but whatever we did she wouldn’t have any of it. On this particular, boat, it was a bust.