The lessons of a catastrophic grounding apply to every sailor who uses electronic charts, says Bill Anderson, who redesigned the Yachtmaster courses

Electronic charts and grounding – a cautionary tale

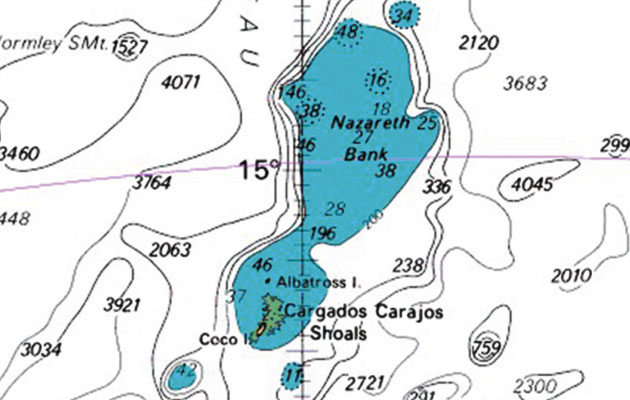

On 9 November 2014 the 65ft Team Vestas Wind, a competitor in the round-the-world Volvo Ocean Race, was 10 days out from Cape Town heading north towards Abu Dhabi. She was on a three-sail reach in a true wind of 14-16 knots, 10° aft of the port beam. Boatspeed was averaging 16 knots with bursts of 21 knots. Shortly after 1900 she emerged from a rain squall. It was dark, the half moon high in the sky astern was intermittently masked by cloud. Suddenly there was a sharp crack, a daggerboard had broken. Rocks were sighted to starboard and immediately an attempt was made to furl the code zero and N0. 3 genoa to depower the boat. The bulb keel, which was canted to port, caught on a rock pinnacle and she swung sharply to port, eventually onto a southeasterly heading, hard aground. All nine people on board escaped serious injury but she was very badly damaged, high and not quite dry on the Cargados Carajos Shoals, a hazard of which the skipper, navigator and the rest of the crew had been totally unaware.

The race organisers commissioned an inquiry and its report, published on 9 March, was written by a small committee chaired by a retired Rear Admiral in the Royal Australian Navy with a lifetime of sailing and offshore racing experience. The other two members have had long, highly successful careers in ocean racing, satellite navigation systems, digital street mapping and sailing administration.

How did a well-equipped, professionally-crewed modern racing yacht end up wrecked on a well charted reef?

Causes and contributory factors

The report looked at the primary cause of the accident and all possible contributory factors. Reading it, one is left with a very clear impression that it was written by world authorities on ocean navigation who are also acutely aware of the pressures that combine to cause navigators to depart from established best practice.

Vestas was manned by an experienced, competent professional skipper, navigator and crew. She carried a comprehensive and complex navigation system, with these components relevant to the grounding:

- Two B&G 6.4in multi-function display (MFD) touchscreens, one in the nav station and one in the ‘tunnel’ between cockpit and accommodation, both with C-Map charts.

- Two Panasonic Toughbooks in the nav station, each with different navigation and routing software: One primarily for weather and routing, with just a basic world map, the other for performance assessment and navigation, with a full set of C-Map charts.

- Paper charts, to enable her to complete the current leg of the race in the event of a total loss of electronic aids to navigation.

So how come that nobody on board was aware of the Cargados Carajos Shoals, a group of low lying islands and drying reefs with a north-south extent of some 36 miles and an east-west spread of about 15 miles?

The skipper and navigator had discussed the shoals but this was probably based on the zoomed-out chart, from which they deduced that the shallowest water was a seamount over which there might be some change in sea state – they had warned the crew of this possibility – but which was in no sense a navigational hazard. The C-Map chart shows only that a larger scale chart is available within the rectangle around the shoal.

Had they consulted the Admiralty small-scale paper chart they carried, or zoomed the C-Map chart in to the same scale, there would have been little chance of missing the significance of the hazard.

Available but not used: if they’d looked at paper charts, or ARCS raster charts, they’d have seen the reef

The investigation specifically does not seek to apportion blame but it does go into some detail on what it refers to as ‘factors which influenced the environment in which the accident occurred’. These included the high workload on the skipper and navigator both during racing and while the boats were in port prior to the next leg, with a busy programme of inshore races, briefings and media events.

Pre-departure navigational planning was also complicated by a last minute change to the race area. An exclusion zone had been imposed to keep competitors well clear of the east coast of Africa, an area of high activity by pirates. Within 24 hours before the start it became evident that a tropical cyclone was likely to cross the course and the obvious way to avoid it would be to enter the exclusion zone. The organisers consulted the agency that advised them on pirate activity and were told that there would be minimal risk in reducing the size of the exclusion zone, as long as the change was not public knowledge. Skippers were told that they could sail in an area that included the Cargados Carajos Shoals only very shortly before the start of the leg.

The report’s conclusions

The simple cause of the stranding was that the crew was completely unaware of any navigational danger in the vicinity of the boat. Consequently no avoiding actions or precautions were taken. Cargados Carajos Shoals were incorrectly thought to be safe to pass over and incorrectly thought to have a minimum charted depth of 40m.

Contributing factors were deficient use of electronic charts and other navigational data and a failure to identify the potential danger, and deficient cartography in presenting the navigational dangers on small and medium scale (zoomed-out) views on the electronic chart system in use.

Download the official report from www.yachtingmonthly.com/VORVestasReport

Is this just a cautionary tale for high-powered professionals racing in distant and unfamiliar waters, of little value to us ordinary cruising sailors? I don’t think so. A report published last year by the MAIB is one of several reasons why.

On the afternoon of 17 August 2013, the 24m motor yacht Isamar was on passage from Bonifacio, Corsica towards Roccapina Bay. The professional skipper, who was on watch, set a north-westerly course at 10.5 knots to pass between the shoals of Grand Ecueil d’Olmeto and Petit Ecueil d’Olmeto. At 1730 Isamar suddenly ran aground. The mate looked over the stern and through the clear water saw an underwater reef. He mustered the guests and had them put on their lifejackets, then went to the bridge where he noticed that the electronic chart display was on quite a small scale. He zoomed in to the largest available scale and saw an area of shoal water, which had not been apparent on the smaller scale.There was no loss of life, but Isamar sank.

The full report into the stranding of Vestas Wind contains a lot more detail than this article. It is worth reading.