James Stevens stands by as Becca Morley steps up to plan and sail her first big offshore passage as skipper

How to plan and sail an offshore passage

James Stevens, author of the Yachtmaster Handbook, spent 10 years as the RYA’s Training Manager and Yachtmaster Chief Examiner

Crossing the English Channel, North or Irish Seas for the first time as skipper is a daunting prospect. You’ll be sailing out of sight of land, crossing busy shipping lanes and tackling ripping tides before you arrive. These are challenges, but not insurmountable ones. A competent coastal skipper handles those situations most weekends. Crossing the Channel is about doing the same things on a bigger scale. If your preparation is good – passage plan, weather, tides and boat checks – there’s no reason you shouldn’t succeed. And, as a first-time skipper, the sense of achievement of arriving safely in another country is like nothing else.

Confidence is a hurdle, but as soon as you have one crossing under your keel, you’ll be ready to go again and again. The aim of this article is to help build that confidence by explaining what’s involved in making a successful crossing. To do this, we needed a first-time skipper, so Yachting Monthly asked Becca Morley, 24, an experienced crew studying for her RYA Yachtmaster qualification, to skipper a boat from Cowes to St Vaast on the Cherbourg peninsula. The boat under her command would be Tamora, a Hallberg-Rassy 34 with Tamora’s owner, James Stevens, Sophie, who had some crewing experience, and Pete, the photographer, as crew.

Why would I want to cross the Channel?

We’ll steer clear of the obvious – pretty harbours, lovely anchorages, a bilge full of keenly-priced wine and a fridge bursting with cheese – and look at the challenge itself. I think the best part of cruising is arriving – and it’s even better if the arrival is in a foreign port. You feel like you’ve actually gone somewhere and achieved something.

If things go wrong, it’s the skipper’s fault, so when they go right the skipper can justifiably bask in having planned and executed a passage that gets boat and crew to a foreign destination. It’s a thorough examination of your judgement and ability as a skipper, and to pass it will boost your confidence in your own abilities and leave you with an immense sense of self-sufficiency.

Skippering is not crewing

There is a huge difference between being the crew and being the skipper. Most crew have very little idea of how much is involved in taking charge of an offshore passage. They stow their bags and they’re ready to go, whereas the skipper started passage planning a month ago and has spent the last week scanning the internet for forecasts, fretting about the drip from the stern gland and wondering about the state of the jib clew.

The paperwork

It’s the skipper’s job to make sure the paperwork for the boat and the crew is in order. The chances are it will go unexamined but if an official does ask for it and you can’t deliver, you could be in a world of bureaucratic and potentially financial pain. Add it to your winter checklist, when there is plenty of time for updating any certificates.

- SSR Registration

- Bill of Sale, as the SSR does not technically prove ownership

- Invoice showing that VAT was paid in the EU

- Insurance certificate

- Passports

- Ship’s VHF Radio Licence

- Short Range Certificate – authority to operate VHF radio

- Certificate of Competence (not actually required in coastal France but well worth having)

- European Health Insurance Card (EHIC – the successor to the old E111)

- Courtesy ensign

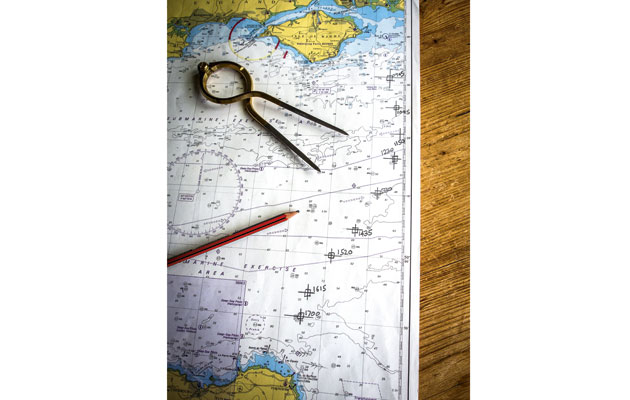

Navigation essentials

You’ll need the right charts and reference books for the passage. For our passage, we made sure we had:

- Electronic chartplotter with C-map charts and a back-up GPS unit

- The Solent Admiralty Small Craft Folio for Solent pilotage

- The Channel Islands Admiralty small craft folio passage chart

- The Mid Channel Admiralty passage chart as back-up

- Imray C32 pilotage chart for St Vaast

- Reeds Nautical Almanac

- Shell Channel Pilot

- Admiralty Channel tidal stream atlas

- Logbook

- An RYA plastic chart plotter

- Dividers, 18 inch ruler, lots of pencils and an eraser

Our first time skipper – Becca Morley

‘This isn’t my first crossing,’ said Becca, 24. ‘I have crossed the Channel dozens of times: it comes with my job. What made this trip so special, and slightly terrifying, is that this time I was in charge!’

After graduating from the University of Sheffield, Becca volunteered as bosun on Provident, a 70 ft sailing trawler that operates sail training for young people. This not only fulfils Becca’s enthusiasm for sailing but also provides challenge and adventure for young people, some of whom are from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Becca has completed the RYA courses up to Yachtmaster Coastal with financial assistance from the Association of Sail Training Organisations and a grant from Trinity House.

Although she lives afloat she has very little opportunity to skipper and practice taking command on small boats.

Preparation and planning

St Vaast, with its locked basin surrounded by oyster beds, is one of the most interesting landfalls on the French Channel coast

This breaks down into three stages: passage planning, which can be tackled a month or more beforehand; checking forecasts from three days out; and boat preparation, which takes place the day before. As this was her first time skippering, Becca and I went through each stage together.

One month before

The proposed trip is from Tamora’s home port of Cowes to St Vaast, on the east side of the Cherbourg peninsula. The best day for the crew is 28 April, if the weather suits.

First, look at the passage chart to get an idea of the whole trip. I prefer a paper chart for this. The shortest route is via the eastern Solent: 69 miles from the Nab Tower to St Vaast. Our destination is a locked basin and there are strong tidal streams near the headland of Barfleur, up to 5.6 knots at springs (28 April is two days before), so it’s important to arrive with a favourable, easterly stream to St Vaast. Fortunately that’s also a flood tide, so we should not have to wait too long for the lock gates to open.

The tidal stream atlas gives favourable east-going tide at Barfleur from six hours before HW Dover (2243 UT, or 2343 BST) on 28 April, so from 1730 BST. It is also favourable the next morning from 0600 but we want a daylight trip.

On average Tamora cruises at 5-6 knots, so from the entrance of the Eastern Solent to 10 miles off Barfleur, 50 miles, will take 8-10 hours. We need to leave the Solent around 0600. The stream east down the Solent is with us four hours after HW Portsmouth (2207 UT, or 2307 BST, the previous day) so from 0300 BST. Wake early and we have favourable tide for the 11 miles to Bembridge Ledge buoy.

The almanac tells us St Vaast lock is open HW-2hr 15 to +3hr 30, or 1915-0100 BST. Note that the tide table for the French standard port Cherbourg is UT-1, which is BST. British tide tables are in UT (GMT). I prefer to stay in BST until we find we have arrived at a restaurant one hour late for dinner, French local time being one hour ahead. If we arrive off Barfleur at about 1730, we should cover the last 15 miles or so at 7 knots with a fair tide and arrive in time for the lock to open. If we miss the tide off Barfleur, or St Vaast looks exposed, we can divert to Cherbourg. The pilot book gives useful hints about the dangers off Barfleur and advice on approaching and berthing in the harbour.

How Becca planned her passage

First time skipper’s thoughts

While planning, an unexpected problem was which time zone to use. I have been taught to do all my calculations in UT, amending for British Summer Time at the end. This works well in home waters. I wasn’t expecting the confusion that arose when working out tides and heights in French Summer Time to ensure I’d get the lock timings right at St Vaast, but I also wanted to convert all my results into BST so that I would be working in one time zone on the day. Cue pages of scribbles and a tide-related headache.

Three days before

Look for a stable forecast. If it keeps changing, the outlook is unsettled. A reliable forecast doesn’t change. For this trip, you need to know the weather for at least 12 hours and preferably beyond. There are plenty of forecasts on the internet but, if in doubt, use the Met Office. It’s the one that is used by the enquiries and disciplinary panels, as I remind my crew.

First time skipper’s thoughts

The forecast is north-east Force 4, becoming variable, not ideal but no reason to delay – we can always motor if the wind dies. Visibility is moderate becoming good – again, it could be better but not a cancelling issue. Had the wind been south-westerly, I might have planned to leave via the Western Solent for a more comfortable wind angle, but it looks like we’ve got lucky!

One day before

Becca victualled for four crew for two days. None of the meals requires much prep, and we could eat from bowls if it’s rough. We have snacks and hot drinks too, and topped up the gas because Tamora’s 4.5kg butane cylinders are difficult to buy in France.

We filled water and fuel tanks, and carried emergency jerry cans of fuel and bottles of water and spares for the engine. Tamora has a decent toolkit and sail repair kit. We checked engine oil, gearbox oil, fresh water in the header tank, drive belt tension, saltwater filter and, once started, that there was cooling water in the exhaust.

The rig was checked a couple of days earlier, the winches had recently been serviced but we missed the broken drive belt in the self-steering system. With four aboard it shouldn’t be a problem but it does need adding to the maintenance list.

We haven’t formally post a passage plan but Tamora’s nominated contact, whose name and number was given to Falmouth Coastguard when her EPIRB was registered, knew when and where we were going and we’d call them when we arrived. Tamora is registered under the Coastguard CG66 scheme.

It looks like an early start so Becca needs to get the crew onboard the night before, talk them through her passage plan and give a safety briefing. As it’s a daylight crossing the watch system is fairly informal: one hour each on the helm in rotation, with another crew on hand. Becca needs to listen to the forecast, estimate passage time and therefore finalise when we need to leave the Solent.

The crew needs to know where the safety kit is and how it works. Walk through the boat and show them

First time skipper’s thoughts

I’m sure I’ve thought of everything, but as I chat through my plan with James I’m worried he’ll think I’ve never sailed before. I talk the crew through the safety briefing, explain our passage plan and that we are to leave at 0530 the following morning, then I’ll settle down to share a relaxed dinner with my crew before an early night.

The crossing – first time skipper’s thoughts

After what feels like 10 minutes in bed, it’s 0500 and the kettle’s on. It’s misty on deck but we can see far enough so, after checking today’s weather, we get ready to go. At 0530, racked with nerves, I spring Tamora out of her berth.

I’m so focussed that small details like setting sails almost escape me. I have courses to steer from buoy to buoy and I’ve made sure there’s enough water outside the channel in case Something Big comes along. Right on cue a pilot boat passes, indicating Something Big. We move out of the main channel and a car carrier steams west up the Solent.

We’re exactly where I planned at 0730. At 5 knots we should be in St Vaast for a late dinner but I’m unfamiliar with Tamora’s performance. If we’re faster, we’ll anchor off until the lock opens; if slower, we have a long tide window but will arrive in the dark.

Once past the Bembridge Ledge buoy, I didn’t spend long plotting a course to steer and just aimed slightly uptide of Pointe de Barfleur. I’ll monitor progress and adjust as necessary. My course takes us into a roadstead of tankers and one starts moving erratically ahead of us. Five hoots of Tamora’s squeaky little horn probably won’t cut it.

In the roadstead east of Wight, Becca hails a ship manoeuvring unpredictably and arranges a safe passage past

The tanker is fine on our starboard bow, making way slowly on the same heading as us. If he turns to port, avoiding action will be tricky under spinnaker. We call him on channel 16, then switch to 72. I identify Tamora and ask if he’s happy for us to overtake to port. A guttural accent says yes, so I thank him and we continue.

Though I’m sick with nerves playing tanker avoidance, the crew needs breakfast. Bacon butties arrive as we pass the last tanker and the ‘fun sailing’ can begin.

Once south of the island, Tamora’s course to steer is west of south, to counter the east-running tide

The wind is perfect. Tamora makes 6 knots under spinnaker and my crew seems happy in the sun. Each takes an hour on the helm and keeps a lookout. All seems well, so I rest below decks before we reach the traffic separation scheme. Though tired, I don’t sleep. I listen for talk of shipping on deck, worry about Barfleur, or the wind veering. I go back on deck to find that we’ve slowed to under 4 knots. It’s time to take the spinnaker down and put the engine on.

We have lunch and numerous cups of tea. I’m pleased with how it’s going and starting to enjoy it. However, it’s cooler now, the novelty is fading as the engine rattles on and we’re all fidgety.

As she usually crews a 70ft steel sailing trawler, Becca underestimated Tamora’s manoeuvrability for giving way as the shipping lanes loomed

We reach the shipping lanes. Without AIS, the crew checks collision bearings with the handheld compass. It doesn’t take long to get the hang of it, deviate less from our course, and we’re soon across the lanes unscathed.

Closing land – first time skipper’s thoughts

We sight Barfleur light on the horizon at 1615. The tricky bit is about to begin. Against instinct, we’re still aiming uptide of the lighthouse to keep it on our port side. Turn too early and we’ll be swept east, resulting in a tedious motor uptide or a different port.

To my delight we are closing the coast exactly when I’d hoped we would, giving us the most advantageous tide. It’s how I planned it! Barfleur whizzes past, looking just as the pilot book promised it would.

I’m following the 20m contour line to avoid rocks and we’re sluicing along at 10 knots. I grasp the binoculars and search for Le Gavendest cardinal, where we turn west, but there are too many other things scattered around. Despite my preparation I can’t make out anything useful. A glance at the chart suggests we should be off St Vaast in 20 minutes. I still can’t see it! At last I spot my cardinal, hidden in a tangle of lobster pots. Suddenly I’m very pleased we chose a daylight crossing.

It’s 1900 BST. I reckon the lock opens at 1915 – hopefully BST, not local. The theory of time zones seems simple; in practice it’s less so. We motor up to the entrance to find a couple of yachts anchored off the breakwater.

Tamora’s young skipper helms her past the breakwater and into St Vaast just as the lock gates open – perfect timing!

I’m about to suggest a brew at anchor when the lock opens. I’ve done it! My crew congratulate

me on getting us here safely, with almost precision timing.

I point out that I still need to park us alongside in the marina. After what has been an exhausting 15-hour journey I’m not particularly looking forward to switching back into exam mode and putting Tamora on a finger berth.

The debrief

The critical decision was the arrival time off Barfleur and Becca got that spot on. On the day, navigation, decision-making, meals and living aboard were fine mid-Channel. The hardest part of the trip was the last unfamiliar 15 miles. For would-be offshore skippers, the lessons are: practice inshore pilotage skills, practice boat handling, and stay rested because the hardest part of the trip is likely to be the end.

Becca sensibly planned backwards from arrival off the French coast. Though she was optimistic in hoping to arrive as the lock gate opened, to her credit, she did. Leaving the eastern Solent Becca successfully avoided ships by keeping out of the main channel and negotiated her way through a roadstead. Victualling, and keeping us happy and fed was not a problem for her as she looks after 12 trainees on board Provident, and she completed the log and kept a record of our position every hour on the paper chart throughout the trip.

Tom Cunliffe’s Shell Channel Pilot (Imray, £35) describes Pointe de Barfleur as a ‘chamber of horrors’, so Becca was wary, but on the day it was benign. She understood the difficulties of the change in time zones but took a while to realise that the reference port for the pilotage chart was Cherbourg and not Dover, as on the passage chart.

Becca kept us safely offshore to avoid offlying rocks, but not so far off that the yacht was swept past St Vaast. Spotting the buoys against the land is difficult. It’s easier to use the plotter to indicate range and bearing so you know where to look, and binoculars with a built-in compass help.

Tamora arrived at Barfleur just as the tide turned easterly –exactly as Becca had planned a month earlier

She worked out the lock opening times and we arrived soon after it opened. Berthing required two attempts but boat handling is always a challenge for the novice skipper.

There were some minor points. Before leaving, she did the final navigation based on the current weather conditions, but could have saved time by getting the crew to prepare the yacht while she did. She helmed for the first hour when she could have delegated that and checked pilotage.

Once clear of land we settled into a watch system, but fine weather meant we were all on deck for most of the trip. Becca rested twice but doing so with ships on the horizon, and again when making landfall, wasn’t the best timing. She found it difficult to judge ships’ range and altered course very early.

Once successfully secured and squared away, Becca heaved a big sigh of relief and downed a well-earned beer. She is well on the way to becoming a Yachtmaster Offshore.

For all the latest from the sailing world, follow our social media channels Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Have you thought about taking out a subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine?

Subscriptions are available in both print and digital editions through our official online shop Magazines Direct and all postage and delivery costs are included.

- Yachting Monthly is packed with all the information you need to help you get the most from your time on the water.

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our expert skippers and sailors

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment will ensure you buy the best whatever your budget

- If you are looking to cruise away with friends Yachting Monthly will give you plenty of ideas of where to sail and anchor