The principles of big boat handling apply to smaller boats, but everything’s bigger – including the consequences of mistakes, says big boat skipper Rachael Sprot

Expert tips for big boat handling

You probably don’t have the desire to own and run a 60ft expedition yacht like mine, but you may well find yourself at the helm of a 50ft charter boat, or helming a larger yacht than you’re used to for a friend. If you do, you’ll soon find out that the challenges are very, very different.

When I first started skippering larger yachts, it was the boat handling I found daunting. I would go to sleep worrying about how I’d get a huge steel sloop weighing over 40 tonnes out of her berth, and I’d wake up in the morning worrying about the same thing. Eventually I realised that it wasn’t worth ruining a good day’s sailing by worrying about the first and last 10 minutes. I made myself some rules to follow and parking became much less stressful.

These rules apply equally well to small boats as they do larger yachts. The difference is that on a big boat, you have to get it right. Hoping that a crew member will jump ashore and save the day is not a sure-fire route to success – the topsides are much higher, making it more difficult to get ashore, and once ashore the boat will be too heavy to manhandle anyway. Big boat sailing is about brains, not brawn.

Rachael Sprot, RYA Yachtmaster Ocean Instructor and MCA Master 200, grew up sailing and has spent her professional life at sea, on everything from wind farm support craft and superyachts to large expedition yachts

- Planning

For parking a big yacht, the most important rule is: choose your berth wisely. Don’t get pressured into taking a berth you’re not happy with. Hint at the potential for collateral damage and most marinas will quickly offer you an alternative, or help you get in. You’ll only kick yourself if you go against your better judgement and have a prang. Once you have found the berth, think through the manoeuvre in detail: where to make your turns, what sort of speed you want and when to change gear. Then brief the crew and prepare lines and fenders.

- Slow is pro

Once you have got a big, heavy boat moving, she will carry her way for a long time. Go as slowly as possible whilst still maintaining steerage. Remember that for every half a knot of speed that you apply before you park, you will have to use an equal amount of power to stop. If you hit something at one knot, it will do a lot less damage than hitting it at three knots. It is also easier to back out when things go wrong if you’ve been travelling slowly.

- Wind on the bow

Most yachts have very little beneath the waterline forward of the mast and the large volume of space for cabins, sail lockers and anchor chain compartments creates a lot of windage. The aft part of the boat has a rudder, propeller and keel, all of which grip the water. Therefore, as soon as you stop in the water and lose steerage, your bow will be blown off by the wind.

- Gear, then steer

1. With the engine engaged ahead, propwash hits the rudder giving you almost instant steerage and control

2. Engage astern and you lose steerage as you slow to a stop. Propwash takes over and the stern kicks port or starboard

3. You won’t regain steerage until you have about half a knot of sternway, which could be some time in a big, heavy boat

Greater momentum means that changing from forward to astern in a tight spot can be perilous. The faster she’s moving, the longer you will need to motor astern to stop the boat – that’s why slow is pro. When she does stop, there will be no water flowing across the rudder so you’ll have no steerage, and that won’t change until she’s moving astern, which can feel like a very long time a confined space. From astern to ahead, you will regain steerage fairly quickly because of the propwash over the rudder.

- Prop walk

I always plan tight turns to starboard, so that Hummingbird’s kick to port in astern works in my favour

Many modern yachts, particularly those with saildrives, experience little in the way of prop walk. However, you still need to assess prop walk and other manoeuvring characteristics of any boat before you enter confined spaces. If the prop walk is considerable then you need to take it into account, even use it to your advantage. Hummingbird has an offset prop, a long keel and a huge rudder. She kicks to port in a big way, and doesn’t like going astern so I always plan tight turns to starboard and park port side to where possible, to utilise the prop walk.

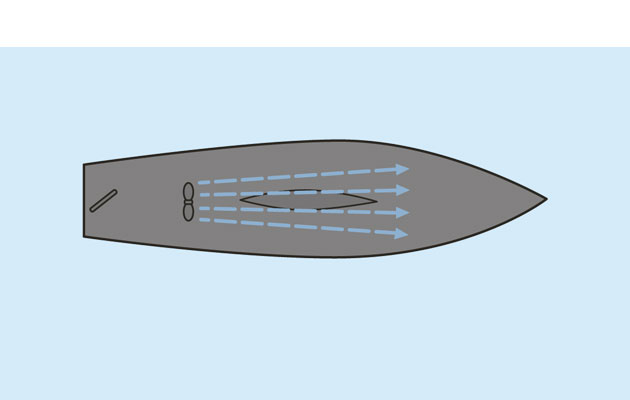

- Pivot points

Make sure you know where your pivot point is, so that you can plan your turns. Going ahead, Hummingbird’s pivot point is somewhere around the liferafts. When moving astern, the hydrodynamic forces on the hull, keel and rudder change and the pivot point moves aft to the cockpit. When you move up to bigger yachts, it is easy to forget how much more boat there is in front or behind you when you turn.

- Master the midships line

Choosing the right rope for the right job really is the key to coming alongside smoothly. We nearly always use a midships spring as the first line onto a pontoon, then motor gently ahead against it with the wheel away whilst we secure the other lines. If you can get the middle of the boat secure, then you have got control over most of the boat. This is also a great technique for short-handed sailing.

- Use your warps

If there isn’t enough space to turn the boat under engine, fender the bow and use lines off each quarter to turn the boat in her own length

You’ll need fendering at the bow, a bow line and two stern lines rigged, one off each quarter. Keep the engine running throughout

Almost without exception, the push-and-shove method of leaving the dock simply won’t work on larger yachts. You need to use springs. Occasionally, even springing off isn’t enough and you need to control the boat through a 90° or 180° turn, or ‘wind ship.’ On Hummingbird we regularly use long warps to control our turn in a tight spot. In the tiny Norwegian fishing station of Grip, the harbour was only just wider than a boat length. We ended up having to use two 50m lines to turn the boat around before driving out.

- Plan for failure

Before any manoeuvre, mooring, berthing or slipping, think about what could go wrong and how best to handle each situation

When planning manoeuvres, consider what could go wrong, the worst-case scenarios, and formulate exit strategies. Will you be able to reverse out of trouble? Is there an easy escape route, or might you have to lie alongside another boat if you can’t get into your berth? Is it worth rigging a midships line and couple of fenders on the other side of the boat? Have you briefed the crew? Planning for the worst makes it far less likely to happen, but if you do lose control, avoid using ‘panic revs’. Drifting onto another boat and securing to her temporarily is much less risky than trying to throttle your way out of trouble.

10. Be creative

Pinned by the wind onto this very berth in the Faroes, a local with a Land Roveron the opposite quay helped Rachael get off the dock

We were in the Faroes last summer waiting for a weather window to make the 600-mile passage to northern Norway. When a window of opportunity arose we were being pinned on to the dock by a 20-knot wind on the beam and couldn’t spring off. After half an hour of trying different manoeuvres, a local fisherman offered to help and gave us a long line to tie to the bow. He took the line round a bollard on the other side of the harbour, tied it to the back of his Land Rover and slowly drove ahead. We came away from the dock beautifully, untied the line from the bow, which he retrieved, and set off for Norway.

Remember: nobody’s perfect

Just after writing this article I damaged Hummingbird’s vinyl wrap while bringing her out of the hoist on re-launch. I went against my better judgement, broke my own rules and rubbed along the pontoon unfendered. I was furious with myself. I pointed out the irony to someone much older and wiser – my mother, Miranda Delmar Morgan, a retired ship’s master.

‘Well,’ she said, somewhat triumphantly I thought, ‘What’s the most useful lesson of all then, Rachael?’

‘I don’t know,’ I replied rather glumly.

‘That everybody gets it wrong sometimes.’

Sail, train explore

Rubicon 3 was set up by Rachael Sprot and Bruce Jacobs to help everyone, even novices, head out to sea for adventure. Based on the ethos of Sail, Train, Explore, their expeditions, which head everywhere from Greenland to Morocco, include full training and time to head ashore and explore.

Tel: 020 3086 7245

Web: www.rubicon3.co.uk