James Stevens stands by as Yachtmaster Coastal Laura McLachlan attempts to plan, sail and skipper her first passage round a headland

How to plan and sail a passage round a headland

James Stevens, author of the Yachtmaster Handbook, spent 10 of his 23 years at the RYA as Training Manager and Yachtmaster Chief Examiner

There’s a lot to consider when rounding a headland. Waves bend around the point. The wind bends too, and can increase in strength as it’s squeezed by the headland. There’s also a good chance shoals off the point will create overfalls. Planning is all-important so YM asked Laura McLachlan, a newly qualified Yachtmaster Coastal, to skipper a Hallberg-Rassy 34, Tamora, for the first time around a well-known headland: Portland Bill.

Portland Bill in full cry

Portland Bill is the gateway to the pleasures of sailing in the West Country for the Solent sailor, but rounding it can be intimidating for the inexperienced skipper. As instructors at the old National Sailing Centre in Cowes, we used to call Portland Bill the ‘Day Skipper’s Cape Horn.’

According to Tom Cunliffe in the Shell Channel Pilot, the Race off Portland Bill can become ‘the most dangerous extended area of broken water in the English Channel’

Click here to watch Stuart Morris’ video, shot during a storm in 2009, and see just how violent conditions can get off Portland Bill in strong wind against tide conditions

It has a fearsome reputation. Tom Cunliffe, author of the Shell Channel Pilot, describes this place as ‘the most dangerous extended area of broken water in the English Channel. Quite substantial vessels drawn into it have been known to disappear without trace.’

There is a ferocious tidal stream off the Bill, reaching seven knots at springs. This creates a race with heavy overfalls, particularly in wind-against-tide conditions, which moves menacingly around the Bill as the state of tide changes. Overfalls can extend up to seven miles offshore.

As if this were not enough, there is the difficulty for westbound yacht skippers that once round the Bill there is about 45 miles across Lyme Bay to go before reaching the sheltered harbours of Dartmouth or Tor Bay. Plus, the strong tidal stream off the Bill means that, once you’re round, changing your mind isn’t really an option.

That said, hundreds of yachtsmen and women, some in surprisingly small boats, safely make the passage year after year, but I am sure they were all anxious the first time – or for that matter on subsequent roundings as well.

Calmer inshore

Usually when a tidal stream flows along a coast and towards a headland, the current is slightly weaker closer to the shore and the stream also shoots clear of the headland, leaving a small area of still water or weak current off the tip. Waves that are moving against the current will be concentrated in the main stream. The narrow strip of sea immediately inshore of the stream then becomes a (relatively) placid inshore passage between the race and the rocks, possibly suitable for small-boat skippers who know what they’re doing.

The photograph faces to seaward and the tidal stream is flowing left to right, against the waves. The race occurs where the water crosses a rocky ledge, with depths of little more than 10m in some places. The zone of strongest current is a seething mass of foam, while near to the land there are fewer breaking crests, although some of the larger waves are breaking because of the shallow depths, and it is unlikely that any sailor would attempt to use the inshore passage under such extreme conditions.

Laura McLachlan

I started sailing five years ago, volunteering for the sail training charity Ocean Youth Trust North, so I’m used to sailing its 70ft steel ketch James Cook on the North Sea, not 34-footers on the south coast. OYT North has been training me up from scratch and I passed my Yachtmaster Coastal a few weeks ago, with the help of a bursary from Trinity House.

Preparation and planning

Laura had about a month to prepare, but was acutely conscious that the trip might have to be abandoned if the weather was poor.

There are two options when rounding the Bill: the inshore passage, which requires passing 300m from the shore in 5-10m, avoiding rocks and fishing pots, or the long way round, three to seven miles offshore. Your choice depends on the sea state. The inshore passage requires precise visual pilotage, so it’s important to choose a date whose tides permit you to round the Bill in daylight. We rounded westwards on Thursday 23 April and, with the breeze in the southeast, the inshore passage was the preferred option. In light winds this can be attempted with the tidal stream running powerfully in the right direction, but I recommend arriving at slack water before a favourable stream, in our case west-going.

There is a shoal on the east side of the Bill, Portland Ledge, but it is worth keeping in shallow water to stay out of the currents that run south down both sides of the Bill. If you arrive at any time other than slack water, there is a danger of being set south into the race where the southerly current meets the east or west-going tide.

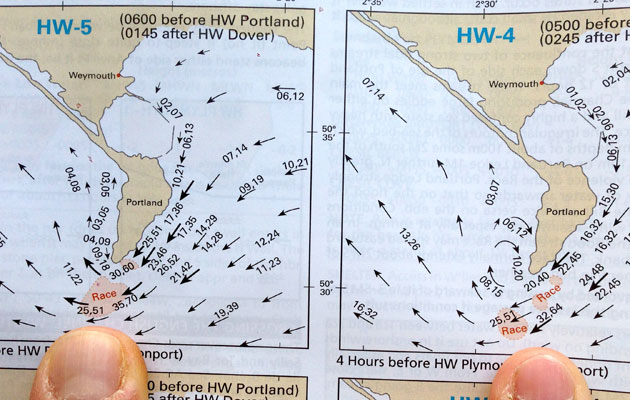

A tidal stream atlas is essential, either from the almanac, pilot book or preferably the Admiralty NP257 Approaches to Portland. Don’t forget that the tidal streams for Portland Bill in Reeds Nautical Almanac and the Admiralty TSA are based on Plymouth tide times, not Portsmouth.

The weather is crucial too – and not just for the passage to and from the Bill. The inshore passage is fine in fair weather, but it’s simply not an option in strong wind against tide conditions. Often the roughest water is not actually off the lighthouse but off to one side or the other. If you’re unsure about the sea state, use your mobile phone to call up the Coastwatch (01305 860178), which maintains a lookout on the Bill.

How Laura planned her passage

As with many UK headlands, arrive at the wrong time and you’ll find yourself shut out by a tidal gate

The race moves depending on the state of tide: another reason why it’s critical to get your timing right

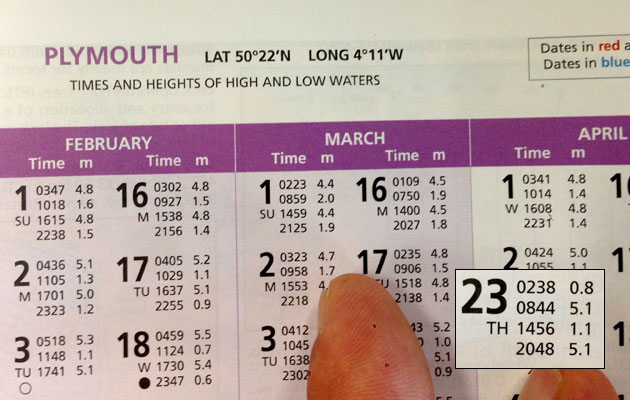

Once you’ve found slack water, between HW+4 and +5, refer to the relevant tide table, in this case Plymouth (Devonport)

With slack water at HW+4h 30 (between HW+4 and +5), and HW Plymouth at 0844 (0944 BST), we need to arrive at 1414 BST

I checked vector and paper charts looking for rocks inshore, as we would need to stay in shallow water

First time skipper’s thoughts

Everything rested on the timings round Portland Bill so I carefully studied Reeds Almanac and the Tidal Atlas. Both used Devonport as the reference port, and it took a good five minutes of looking in both books, and finally resorting to Google, until I realised Devonport was another name for Plymouth. I worked out I wanted to arrive at the Bill between HW+4 and HW+5, so HW+4h 30 BST Plymouth, which today was 1414. So that meant I needed to leave Portland by 1314 at the very latest. We’d have the tide pushing us south, and then the tide with us across Lyme Bay too. I kept checking the tidal atlas and repeating the calculation since it was absolutely vital that we got it right!

One day before

The passage was planned to start in Portland Marina, about six miles from the Bill. This allows an accurate ETA for slack water and a last-minute weather check in the marina office.

Approaching from the west, across Lyme Bay, you do not have the luxury of timing your arrival so accurately. It’s likely to be during the easterly flood tide with a strong set to the south on the western side of the Bill, with patches of rough water to the south and southeast, making it even more important to stay in close. If it is getting windy – particularly if you’re beating – go offshore, outside the race.

A sailing instructor colleague was knocked down in a 32ft yacht off Portland Bill so it is worth wearing a lifejacket and harness and making sure the yacht is secure below. I’ve never had any serious trouble but it can be rough.

The wind can be fickle, often blowing harder on one side than the other so if in doubt reef because it could be difficult working on deck in rough water the other side. You can see the overfalls so even if you are unable to avoid them you know what’s coming. Clip on and get the washboards in.

First time skipper’s thoughts

I got up in the morning with the wind light and in the east. The forecasts said that, by the afternoon, we should have southeasterly force 3-4, which would be fine. We crossed our fingers that the forecasts were right.

Reading the pilot book also had useful information. It warns against lobster pots so we needed to keep a good lookout. They get pulled underwater by the stream.

It also advised staying within 1.5 cables of land, so it was important I made sure I was happy with using Tamora’s chartplotter and radar so I could keep an eye on this. However, I also didn’t want to get too close because the chart showed rocks.

I did a tidal curve so I could use the five-metre contour as my boundary. The pilot book also highlighted the strong southerly tides have a real chance of setting you into the race, so keeping an eye on this and my course over ground would be an important one to watch.

With passage and pilotage plans done, I walked through the boat and gave everyone on board a safety brief, cleared the deck ready to leave, and did the daily engine checks.

Changing breeze

Around Portland Bill, winds will form eddies and squeeze between the Bill and the mainland. Changes in direction as the wind fans out over Weymouth Bay are well known – and used to win races by dinghy sailors with local knowledge. What happens on specific days will depend on the direction and strength of the wind approaching the Bill. As always, local knowledge and careful observation will pay handsome dividends.

Rounding the Bill

Since there was the potential for things to get quite rough, even in moderate winds, it was important to prepare the boat and crew appropriately. I made sure everything was stowed down below so that it wouldn’t end up flying around the saloon or cabins if we were rolling around at sea. I made sure all on board were fitted with lifejackets and harness lines, and that the jackstays were ready to use. I briefed the crew and double checked that everyone’s lifejacket fitted properly and that everyone was happy using lifejackets, tethers and jackstays since everyone was to wear their lifejacket when on deck at sea, and depending on the conditions we might need to clip on.

It could get rough down at the Bill so we all adjusted our lifejackets to fit and checked the jackstays were secure

At 1300, after an early lunch, I decided it was time to leave. The wind had built a touch as forecast so all was well. We were being blown onto our berth, so we had to spring Tamora off. As we motored out, I was feeling nervous but excited to get going.

I marked our position on the chart and monitored course over ground, mindful of ending up in the race

We motored out of Portland using the fairway, avoiding a few boats that were racing along the way. I was piloting and helming while James put the sails up since it was just the two of us. My pilotage plan came in very useful as I could pilot us out safely while being on deck the whole time. Also, getting the chance to helm for a few moments did wonders for settling the nerves. It always makes me feel at ease.

After turning south-east out of Portland Harbour, we put the main up but it was too close to the wind for us to sail. Since timing was so critical to this passage, I made the decision to motor sail rather than tack our way south down the eastern side of the Bill. James helmed so I was free to keep a good eye on the navigation.

Turning south, we did manage to turn off the engine and sail a little bit but, as we got closer to the Bill the wind kept going right and it was again too close, so we began motor sailing again. I spotted my first lobster pot – and the pilot book was right, they really do get towed underwater by the tidal stream! They were just tiny little balls with no marker flags and mostly underwater, so we would have to be vigilant.

I realised we were too far offshore so closed the land – heading straight for Portland Bill lighthouse

As we passed Grove Point, the Bill’s eastern extremity, I decided I was too far away from the land, in water too deep, as we were still being pushed south strongly by the tide – exactly what the pilot book had warned me about. I didn’t want this to happen so I plotted our position and made a course change that had us heading at the Bill. I checked the course over ground – this was perfect for putting us back on track, but I realised I’d still need to keep a careful watch on this.

We got back within 1.5 cables of land after lots of checking of the chartplotter and course over ground, making little adjustments to fine-tune our track. It was totally against my every instinct to be so close to land, particularly as it was a lee shore as well. It made me very nervous, but it was important so we didn’t drop south into the race so we had to stay in the shallows, out of the strongest south-running stream. However, as we followed the coast, it was an impressive sight being so close!

We tried to stay 1.5 cables away at all times, not getting much closer due to the lee shore. We kept checking the depth too, and that was as expected and never set any alarm bells ringing. We kept checking both depth and distance off all the way round. There were a few small signs of the race, but nothing too dramatic. The planning had paid off and our timing was spot on!

‘We’re west of the Bill!’ Laura allows herself a smile before putting on the kettle and heading towards Torquay

Now we were past Portland Bill I could breathe a sigh of relief and relax a bit. I put the kettle on, raided the ship’s supply of biscuits and aimed our bows across Lyme Bay towards Torquay, with the wind on our port quarter.

The debrief

James Stevens, author of the Yachtmaster Handbook, spent 10 of his 23 years at the RYA as Training Manager and Yachtmaster Chief Examiner

As a maths undergraduate, Laura effortlessly calculated the tides for this passage, helpfully writing down her results for those of us with less mental agility, so we had no problems with the navigation plan. Her theory was excellent.

The day started with a light easterly – a good direction for our rounding. Luckily the wind built a touch and went right, so it was ideal by the afternoon. Had we awoken to the sound of wind howling through the rigging, we would have to face the possibility of abandoning the trip. For a downwind passage and wind with tide, anything over a force 6 makes the inshore route marginal.

Laura holds a Yachtmaster Coastal certificate and her boat handling was cautious but proficient. Her plan and departure time had assumed northeasterly or easterly winds but during the morning it veered to southeast so when we came out of Portland Harbour we were unable to sail our course without tacking. As timing was critical we motor sailed the first part until we could bear away to the Bill.

Her only minor error was to stand too far out to sea on the way to the point. It’s understandable that a new skipper in a borrowed boat would want to keep away from the lee shore, but for Portland you need to take a deep breath and go in close to avoid the race. After changing course to steer towards the lighthouse, we arrived in the right place exactly at slack water, so the Bill, with its fearsome reputation, provided no dramas. We slid past enjoying the spectacular coastline in the sunshine.

We were well briefed before the trip and, in spite of the sunshine, were dressed to get wet in case we drifted into overfalls and pushed the bow into rough water. In fact we managed to avoid any rough water, mainly through timing the arrival perfectly.

The tidal curve in Laura’s tidal passage plan helped us stick to the 5m contour as we closed the Bill

Although Tamora has radar that provides an easy way of maintaining a distance from the land, Laura kept the advised 300m off the shore by referring to the chart plotter, which put us in exactly the right place. She wisely stayed on deck as much as possible to ensure the sails were trimmed correctly and that we avoided lobster pot buoys.

She was clearly anxious about skippering a passage around a notorious headland, which she had never been to before, but she made good decisions and had a relaxed style which gave us confidence. She had clearly worked hard at the preparation, read the pilot book and gleaned as much information as she could. Had the wind stayed fresh or increased she would have been faced with a really difficult decision – whether to attempt the inshore passage or go round the long way, or even abandon the trip altogether.

In spite of the dreadful warnings in the pilot book, rounding Portland need not be fearsome. With careful planning and a healthy dose of caution, even the first time skipper can get round in comfort, and with confidence.