Reefing: how, when and why do we do it? The answers may not be as straightforward as you think, says James Jermain

Essential reefing tips for cruisers

James jermain, boat test guru and former editor of YM, has sailed hundreds of yachts all over the world

Why do we reef? Simple. We reef when conditions are such that to do otherwise would risk blowing out the sails, bringing down the mast – or driving the boat under.

But stop there and you’ll have only half-answered the question. You will have missed out the most important factor – the crew. You may well also be guilty of not understanding your boat and the way she behaves. Most boats, particularly modern boats, share with their crews a liking for sailing upright, under good control and comfortably.

With too much sail up, the mainsheet trimmer will be worn out working the traveller – and one lurch away from a fall across the cockpit

In short, thrashing to windward at 30 degrees, tiller under chin, main flogging and spray sweeping the cockpit, may be exhilarating and macho for a short time, but your crew will quickly lose the will to sail with you ever again. You will also be shortening the life of your gear and, you may be surprised to see, the nicely snugged-down boat that was somewhere over your leeward quarter is now stretching away on your weather bow.

Newcomers to sailing often take a while to shake off the notion that the stronger the wind and the bigger the sails, the faster you can get the boat to go. But that’s definitley not the case.

Take a moment to consider the shape of your boat underwater when she’s sailing on a more or less even keel – she has nicely flowing curves, well balanced on both sides. The rig is standing over the boat with the centre of effort driving forward more or less along the centreline and over the bow.

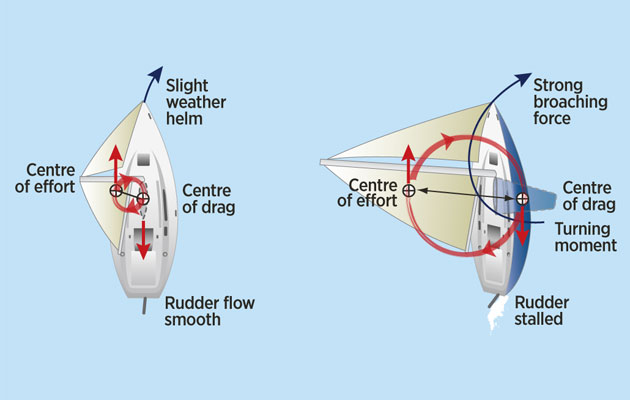

Upright, water flows evenly around the hull. When heeled the water flows very differently, encouraging her to round up

Now picture the boat heeled to 30°. On one side the waterline is a sharp curve, the other almost straight. The hull is trying to hook up to windward and to compensate you have to pull the rudder hard over across the water flow, where it acts more as a brake than a steering foil. The keel is no longer as deep, has less grip on the water and its centre of resistance (drag) is to windward of the centreline.

Heeling increases weather helm due to different waterline profiles (see above) and the turning moment that results from the separation of the Centre of Effort and Centre of Drag. Reefing reduces heel, bringing them closer, so reducing weather helm and improving waterline profile

Meanwhile the rig is well over to the lee side. The centre of effort is somewhere over the sea to leeward and is also dragging the boat round into the wind. You are having to stall the main and lose drive just to keep the boat under control. You are going slowly, sailing further in a series of curves, and leeway is carrying you off your course.

And we haven’t even started to consider the lot of the poor crew hanging on by their fingertips, wet, tired and considerably below mental and physical par.

So the answer to ‘Why do we reef?’ on a cruising boat is to:

- Preserve and protect the crew

- Preserve and protect the boat and equipment

- Sail faster and more efficiently

When to reef?

An old adage states that: ‘The time to reef is when you first think of it.’ And it’s true. In a cruising context, you will seldom regret reefing early and you will almost always regret reefing late. In practice choosing the right moment to reduce sail is a matter of knowing and understanding your boat, your crew and the conditions – in other words it’s ‘experience’. However, here are some reasonably reliable guidelines for a typical modern, medium-sized cruising yacht:

- Wind speed

Most boats are designed to require the first reef in around 18 knots apparent wind when sailing to windward. Some lighter, more coastal-orientated boats may struggle in 15 knots while heavier offshore designs will still be happy at 20 knots or more.

- Heel

Heavier displacement boats like this Hallberg-Rassy can wear their canvas longer than lighter boats, but she still seems heavily pressed

Few boats are efficient at more than 25 degrees of heel, and that applies to the crew as well. Excessive heeling makes the helm heavy, increases leeway and gives the boat a tendency to round up into the wind.

- Sea state

The sea state can have an important bearing. Short, steep seas can stop a boat in its tracks and one that is over-pressed will drive its bows into the face of a wave. Reducing sail, particularly the headsail will allow the boat to ride over the waves comfortably and keep up speed. However, there is another side to this – by reducing sail too much you may not leave enough power to make way against big seas. Knowing your boat will allow you to balance these factors.

- Crew ability

As the wind builds so do the loads on the control lines – sheets, halyards and reefing pennants. A thoughtful skipper will know the strength of his crew and won’t hang on to sail beyond their ability. This is especially true if it’s necessary to go up to the mast or foredeck as part of the reefing process. An over-pressed boat is a much less safe working platform. The thoughtful skipper will also bear in mind the possibility that things might go wrong and need time to resolve – do you have this time and can your crew work in the current conditions?

How to make reefing easier

One reason people delay reefing is that it can be hard and potentially dangerous work. Make it quicker and easier and it will be done sooner.

Mark where everything needs to be for each reef – main halyard, kicker, reefing lines, sheet cars, genoa foot, backstay

Doing all you can to make reefing easier and quicker, which includes servicing winches and furlers, will be popular with the crew

Service, maintain and lubricate (as appropriate) all reefing equipment – roller furling gear, winches, jammers, sheet cars, batten cars, main traveler

Consider equipment upgrades: blocks instead of cringles, stack pack and lazyjacks, full length battens (that reduce flogging and noise and set flatter), better luff cars/slides, more powerful roller furling

The best way to trim reefed sails

Just because there is plenty of wind and the boat is making good speed doesn’t mean sail trim can be ignored. On the contrary, the boat will be operating close to its limits so every scrap of sail efficiency will help. Poorly set sails will add to leeway, which is probably already quite significant. They will also reduce the drive available to cope with big waves while increasing the yacht’s heeling and crew’s discomfort.

Mainsail

When the headsail is half-furled, the slot between the sails is much bigger, so you can ease off the traveller or mainsheet

The big thing to remember is that, with less genoa overlap (assuming it has been partly rolled), and a more open slot, the mainsail can be eased out significantly. Drop the traveller down as far as you can without stalling the luff and even be prepared to accept a bit of lifting here. This will keep the boat more upright, reduce leeway and increase forward drive.

Keep the sail flat. Make sure the leech cringle is hard down to the boom to stretch out the foot, harden up the halyard and increase backstay tension.

Headsail

With the car forward, the sheeting angle of a well-set headsail bisects the clew, balancing the load along the leech and foot of the sail

The important thing here is the sheet lead. As the sail is rolled the lead needs to be moved forward to maintain the angle through the sheet, roughly bisecting the clew. The aim is to balance the load along the foot and leech, so that there is not too much twist in the sail or too much fullness. Make sure you have tell-tales that are still visible when the sail is well rolled so you can position the sheet car accurately. There is not much you can do with the halyard once the sail has been rolled, but before you start, do check that the luff is well tensioned to flatten the sail and remove luff wrinkles. This will make the sail roll more easily and set flatter. Backstay tension will also improve set, by reducing forestay sag.

How to reef when sailing off the wind

So far we have looked at reefing with the boat hard on the wind, round to a beam reach. From this point on you need to consider some extra factors.

For one thing, once you are running off downwind, apparent wind drops away, the boat comes upright and all seems to be well. Always be aware of the true wind speed. It is all too easy to ignore a rising wind in the thrill of a high-speed downwind sleigh-ride. Never lose sight of what conditions might be like if you suddenly had to turn into the wind.

I’m not suggesting you should run with a sail plan reduced to cope with an upwind beat (although on a catamaran it’s not bad practice), but remember it’s not always easy to reef downwind and you may have to round up at least to a beam reach before you can manage it.

The problem with reefing downwind is that you can’t depower the mainsail. Luff slides can jam and the main will drape over the spreaders

The problem with reefing downwind is that you cannot depower the main. As soon as you ease the halyard, the sail will tend to fall across the shrouds and spreaders, particularly if they are swept well aft. The pressure in the sail will also be forcing it forward onto the mast and the slides/cars will tend to jam in the track. Dragging a sail down over the spreaders and shrouds, even if it is possible, will almost certainly cause damage.

The genoa is much easier to reef downwind. The loads are light and the reefing line will be easy to pull in. The genoa also tends to pull the boat along, rather than push it, so it generates less broaching movement.

Everything, therefore points towards reefing the main early and deeply and then fine-tuning the total sail area with the genoa.

But, you may say, on a deep run, the genoa won’t stand well. The answer is to pole it out or sail high enough to keep it filled and stable. Tacking downwind not only keeps the genoa filled and stable, but it can also be faster, or as least as quick as, a dead run. This is particularly true of lightweights and catamarans, but less so for heavy displacement long-keelers.

Reefing theory in practice

As all sailors know, the theory is only half the story. Things can be a lot less predictable out on the water. We went sailing in the Solent in perfect wind conditions for reefing research. The breeze built from nine to 24 knots apparent to windward (three to 18 knots true or Force 2 to 5), giving realistic conditions for taking in one and then two reefs. More to the point, it showed exactly why early reefing really works.

Our boat was a Jeanneau Sun Fast 37 on loan from the Hamble School of Yachting: a fast cruiser-racer with a roller furling headsail and a slab reefing mainsail.

As the apparent wind rose above 18 knots, we suffered the first of a series of broaches. While maximum boat speed remained reasonably high (just over six knots), the average course to windward fell from around 33 degrees to closer to 40 degrees as leeway increased, and continually rounding up lowered our average speed.

The mainsheet trimmer was having to work hard dropping the traveller and easing the main to keep the boat on her feet and all control lines were fully loaded.

Much better! Less power, but less hard work, more boatspeed, a lot less leeway and a happier, more comfortable crew

As soon as we eased off the main in preparation for reefing, the boat came upright and the cockpit was a nicer place to work. The first reef dropped in quickly, and six rolls of the genoa brought it down to working jib size. We sheeted in, trimmed the sails and immediately the boat gained half a knot top speed. More importantly, she was able to maintain that speed and hold a wind angle of 33 degrees without rounding up. She still had the power to drive through a short chop, the mainsheet hand could relax and life in the cockpit and below was much more civilised. As the wind approached 24 knots, the same procedure was repeated, with similar results – easier motion, increased speed, more comfort, less leeway, less work.

Reefing on cats, cutters, ketches and yawls

Catamarans

The problem with cats is the stronger the wind, the faster they go, until…

The signs that a cat is over-pressed can be subtle and take some experience to sense. So reefing a cat is largely a numbers game – first reef at x knots in flat seas, x-y knots in heavy seas, x-z in breaking seas. Sea state is almost more important than wind strength. The big danger is burying the lee bow and pitchpoling. Reduce the often large and big-roached main area ahead of the smaller jib and you will keep the downward pressure to a minimu

Cutters and ‘slutters’

Twin headsails allow great flexibility in reefing. Traditional cutters with a high-cut yankee jib and small (self-tacking) staysail, can be reefed by dropping one or other sail, the remaining one being left in conditions up to gale force. Modern ‘slutters’ with a big, genoa-sized headsail and a smaller staysail are usually sailed single-headed, with the genoa often full cut and used only in light airs or off the wind. In wind of 15 knots or more, the headsail is furled and the small, tough staysail can again cope with winds up to gale force.

Ketches and Yawls

Although out of favour for good reason, twin-masted boats are often perfect for heavy weather sailing, being able to set or dowse a number of sails in many combinations without having to reef or roll any of them. The boat can always be well balanced and the sails set most efficiently.

Enjoyed reading this?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.