For home-waters sailors who are considering a holiday cruise to France, Ken Endean looks at the options for making a dash across the English Channel

For yachts based on Britain’s South Coast, a sail to France is an obvious holiday destination and a crossing of the English Channel leads to some very attractive cruising grounds.

There’s the prospect of French cuisine, canal routes to the Mediterranean, and the craggy inlets of Brittany, with the opportunity to coast-hop into the warm weather of North Biscay.

Ile Houat in South Brittany could be a sunny treat on a longer cruise. Credit: Ken Endean

A lot of the crews that undertake to sail to France are families who are learning the ropes, rather than hardened offshore experts, and their plans may be limited by the duration of their annual summer break.

It is not possible to thoroughly explore the French coast and Channel Islands in two or three weeks, so it pays to make a realistic appraisal of what can be achieved, allowing some slack for bad weather and hold-ups.

Sail to France: Destinations to visit

The first step is to decide where you want to go, and what style of holiday you are looking for.

Northern France is a cruising ground of two halves.

East of Cherbourg’s Cotentin Peninsula, the coastline is relatively smooth on plan.

There are few offshore hazards but also few sheltering headlands; almost all the inlets dry out and most of the minor harbours are inaccessible at low tide.

Brittany’s craggy inlets include many good anchorages, like this one at Port Blanc. Credit: Ken Endean

Cruising here means sailing from port to port and the rewards include French culture and history.

West of Cotentin, everything changes and lots of islands and rocks are scattered around, so the navigation becomes more intricate but there is also a greater choice of sheltering havens.

First-time visitors may be alarmed by rearing lumps of granite but experienced voyagers relish the dramatic coastal scenery.

It is also possible to head deep into the Breton estuaries, to old inland ports such as Pontrieux, Treguier and Morlaix.

Within this western area, the Channel Islands offer an intermediate experience: jagged rocks with French names but English language and lifestyle, with a few local tweaks.

The best routes to sail to France

The chartlet shows a selection of possible tracks for the initial Channel crossing, with approximate distances.

Working from east to west, the shortest route is across the Straits of Dover but if we want to cruise south there’s little point in heading for Calais, when Boulogne is only a few miles further.

There are several long, narrow banks, aligned roughly parallel with the coasts, and they are shallow in places, but in fair weather it is possible to cross them safely with sufficient rise of tide.

Sail to France: Fécamp has all-tide access to its outer basin, but the entrance is exposed to northerly winds. Credit: Ken Endean

Between Boulogne and Cherbourg, the only all-tide harbours are Dieppe, Fécamp, Le Havre and Ouistreham, so passages to other places should be planned for arrival around High Water.

In most harbours, moored yachts lie afloat, either in dredged areas or gated basins, where fin keeled craft will be quite happy.

For boats bound for the Med through the canal system, the usual entry points are via Calais or up the River Seine from Le Havre.

West of Cherbourg there is a mixture of all-tide ports, gated harbours and sheltered anchorages, while the complicated geography permits various permutations of passage tracks and destinations.

Many French yacht owners like to take the ground on drying moorings and sandy beaches, so twin keels, lifting keels or beaching legs are desirable for visitors who wish to blend in with the local sailing scene.

Yachts with a draught of less than 1.2m may access the Breton Canals via St Malo and the Rance estuary, for an overland voyage across Brittany.

Wind and sea state

There’s not room in this article for a detailed analysis of English Channel meteorology but I’ll mention a couple of phenomena that are particularly notable on the French side.

After a strong blow from the SW quadrant, winds in the Channel often veer to NW, which is fine for flatter water on England’s South Coast, and excellent for fast southward crossings, but much of the coast of France becomes a lee shore.

At the eastern ports, such as Fécamp, arriving at a narrow harbour entrance with a strong onshore wind can be nerve-racking, while at the western destinations there is more chance of gaining some protection from islands or promontories during the approach to shelter.

In fine, high pressure weather, the background wind is often from the NE quadrant and thermal influences – the sea breeze effect – can modify the direction and strength.

Estuary mist in the morning may well disperse over open water. Credit: Ken Endean

Thermal breezes are caused by heat reducing atmospheric pressure over the land, and they like to blow towards the shore, then veer so that the land is on their left.

East of Cotentin, this will encourage stiffer NE winds and more rough water at those harbour entrances, although that scenario is ideal for sailing westward.

West of Cotentin, sea breezes usually blow into the Gulf of St Malo.

Weak NE winds can intensify to Force 5 or 6 through the northern Channel Islands, where some of the most popular anchorages for sunny days, such as the beach by Herm Harbour and Sark’s Havre Gosselin, are protected from the NE.

Further west, warm sunshine often generates a northerly breeze blowing around the end of Brittany.

Strong east winds are generally associated with low pressure areas over the Continent, and in summer these lows cause trouble if they track north across the Channel, typically producing thunderstorms with sudden squalls, heavy rain and then a wind shift to west.

There are anchorages that offer shelter from east winds but we won’t stop there if a thundery low is likely to pass over during the night, because we could wake in a stiff westerly and stern-to a lee shore.

Sail to France: The drying anchorage at Herm Harbour is perfectly sheltered from north east winds. Credit: Ken Endean

During strong winds from east or west, the sea state in the English Channel becomes somewhat rougher when the tidal stream is flowing to windward but the wildest water occurs in the tidal races, notably off Portland and around Alderney.

They also kick up a fuss when the streams flow against incoming swell, even when the wind is light.

Muscular Atlantic swell is most likely to be encountered west of Cotentin, where it occasionally pounds the harbour entrances at places like Carteret, and particularly around NW Brittany.

Shorter swell waves also come south through the Straits of Dover when strong northerlies blow down the North Sea.

Tidal streams and navigation

During a Channel crossing, tidal streams of up to 4 knots induce considerable lateral drift.

Most sailors know that there is no point in trying to continually compensate for the current by steering so that the boat tracks down the rhumb line.

It is much better to estimate the net tidal vector, with east and west flows partly cancelling out, and then set a course to offset it.

However, for a really efficient crossing the calculations should be re-worked at intervals.

St Peter Port’s outer harbour has pontoons with all-tide access. Credit: Ken Endean

For each hour I normally plot the GPS position and also the course and logged distance from the previous fix.

The difference shows our actual drift plus leeway, which may disagree with tidal atlas figures and enables us to fine-tune our tactics.

Last time we crossed from Salcombe to Guernsey, we had planned to go around the south of the island.

But after several hours of a belting broad reach we realised that we had a good chance of holding our flood tide to the northern end, and finally saved a couple of hours by going around that way and down the Little Russel to St Peter Port with the ebb.

Sail to France: Shipping and fog

In the Dover Straits, shipping is very busy but generally well-disciplined and predictable.

Once we passed several groups of Channel swimmers, with escort boats, that were (literally) crawling across the traffic separation scheme.

The Coastguard had broadcast warnings and huge container ships were meekly lining up to pass between the groups.

Further west, most of the commercial traffic follows a straight track between the Dover and mid-Channel separation schemes, although some ships diverge towards Le Havre or the Solent, or to anchor in Lyme Bay when awaiting orders.

In recent years, I fancy that commercial vessels have begun to pay more attention to yachts.

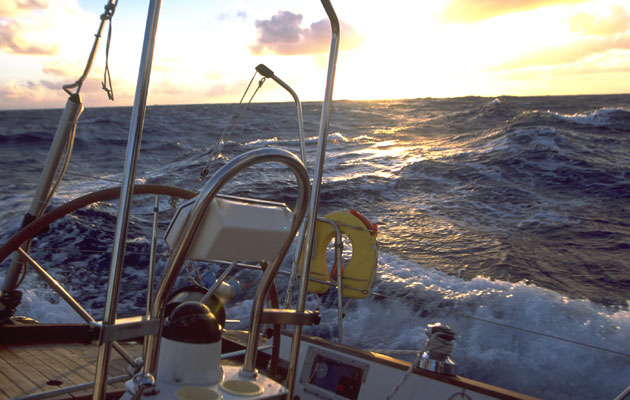

Broad reaching for Guernsey, with a fair tide. Credit: Ken Endean

This could possibly be because a couple of accidents have led to well-publicised prosecutions of merchant skippers, or because some yachts use AIS to call up ships and clarify their intentions.

So long as GPS is working, navigation in fog is no longer the problem it once was, but for many sailors a combination of fog and shipping is the ultimate horror.

The obvious advice is to not sail when fog is forecast, but if the worst happens and you happen to encounter a patch of thick murk, I’d make two suggestions.

Firstly, no matter what electronic aids are available, keep a good lookout on deck and avoid unnecessary noise.

If a fast yacht or powerboat comes out of the fog bank it may not have shown up on AIS or radar but an alert watchkeeper may well hear it, or see it in time to take avoiding action.

In pre-GPS days we once sailed into Alderney’s Braye Harbour in thick fog with the engine turned off so that we could hear the breakers on the rocks to port of the fairway.

Secondly, maintain a good speed, even if that does mean some engine noise.

A few years ago, a yacht’s crew picked up a ship on radar and stopped to let it pass ahead but they had mis-read their radar and were run down while stationary.

If a 10-metre yacht crossing ahead of a Panamax container ship is cracking along at 6 knots, she will be in the direct path of the ship for only 15 seconds, and also has a chance of taking evasive action.

Cross-Channel strategies

There is plenty of published guidance on seaworthiness, emergency equipment and rough weather, so I don’t propose to repeat it here.

Rather, I’d like to consider a little psychology.

The saying: ‘To travel hopefully is better than to arrive’, is actually pretty daft when applied to cross-Channel cruises.

The routes to sail to France. Credit: Maxine Heath

Travelling hopefully is all very well but failing to arrive in France would seriously spoil the effect.

In practice, the problem is the other way around: although the hazards are real enough, the vast majority of small boats that set off across the Channel do arrive safely but some crossings prove decidedly stressful for all concerned.

In some family crews a few members even prefer to cross by ferry before re-joining their yacht on the other side.

That may be an attempt to avoid seasickness but in many instances it also seems to be a reaction to frightening stories about commercial shipping, possibly compounded by previous bad experience when a change in the weather turned a straightforward crossing into a violent thrash.

Sail to France: The old gated basin at Morlaix has pontoon moorings for visiting yachts. Credit: Ken Endean

My first three cross-Channel cruises as a skipper were around 40 years ago, in a Hurley 22 with a family crew of four, including two toddlers.

By today’s standards the boat was small and her equipment primitive.

We had no GPS or even Decca, and initially no VHF, but we always arrived safely, although there were some unpleasant conditions and we gradually developed an appreciation of how to de-stress a passage so that it was enjoyable, even when circumstances conspired against us.

Nowadays our main policy is to build some slack into each passage plan, and into our overall cruise programme, so that when we encounter a difficulty, we can avoid it rather than having to struggle against it.

If the holiday programme for France includes a few ‘spare days’ then spells of strong wind can be spent relaxing in shelter.

Similarly, spare hours in a crossing plan will allow for unexpected developments.

It is possible to shorten a crossing time to France by several hours if we start from a forward departure point.

Anse de Berthaume, outside the Rade de Brest, is sheltered from north winds. Credit: Ken Endean

This is why the chartlet (above) shows short mid-channel crossings from anchorages at Swanage, Hurst Point and St Helens, rather than from (say) Poole, Hamble and Chichester.

This tactic should also allow more time for arrival in daylight, or perhaps before the harbour gate closes at St Vaast.

Further west, we could shorten a passage from Falmouth if we start from a Lizard anchorage such as Porthallow.

Continues below…

Cruising after Brexit and sailing in Europe

As Europe begins to open up again for cruising, Lu Heikell looks at the implications of Brexit on UK sailors…

How, when and why to cross Biscay

Crossing Biscay is an offshore rite of passage like no other. Atlantic circuiteer John Simpson talks to Chris Beeson about…

Mediterranean sailing: where to cruise

Home to a hugely diverse cruising area, whether on your own boat or on a charter, there are literally dozens…

Cruising northern Europe: The best places to sail to

Miranda Delmar-Morgan recommends a few of her favourite places to sail when cruising northern Europe between Atlantic France and the…

At the French end of the passage a similar principle applies; traditional pilotage advice recommends heading for estuary destinations such as Lezardrieux or L’Aber Wrac’h, because their approaches are well marked, but we now prefer to stop at outlying anchorages such as Isle de Bréhat or Corréjou.

This knocks miles off the crossing, probably allows us an undisturbed evening, and also leaves us well positioned to move on in the morning.

Another aspect of passage timing concerns tidal gates.

If we will be negotiating a place of strong tides I would rather plan to get there when the stream is about to turn in our favour, rather than when it is about to turn foul.

In uncertain weather, if we do decide to sail, it’s useful to identify a contingency destination that is further downwind, so that we can respond to a strengthening or heading wind by simply bearing away rather than bashing on.

The chartlet shows St Vaast and Roscoff (or Ile de Batz) as fallback alternatives to Cherbourg and L’Aber Wrac’h, respectively, if a westerly wind might back towards south west or south.

From St Malo, the Breton canals offer an overland route to Biscay. Credit: Ken Endean

Keeping the wind abaft the beam, where possible, will also keep the crew dryer and warmer.

Having a few hours in hand also allows scope for taking advantage of favourable wind shifts.

At the western end of the Channel the crossing routes to France are too long for most yachts to complete in daylight hours.

We like to plan for a day-night-day crossing, to approach Brittany fairly early on the second day.

The Chenal du Four and its approaches are partly sheltered by the western Breton Islands and if the wind heads us we could stop at L’Aber Ildut or Ile Molène, but on our last crossing, from the Isles of Scilly, we finished with a boost.

We had been driven by a fresh NW wind, which faded north of Ouessant, but we had time to spare and drifted for a while, until the local sea breeze kicked in and slid us through the Chenal du Four in fine style, to anchor in the Anse de Berthaume, outside Brest.

If we had needed provisions, Camaret would have been a convenient alternative.

Exploring France and the Channel Islands

Everyone will have their own ideas of what to do in France and the Channel Islands, but sailing from place to place becomes most enjoyable when we feel familiar with the coastal geography.

To that end, I’ll make a couple more suggestions.

The first is that tides are critical, and not just the strength of their tidal streams.

In the eastern Channel, for most harbours, the times of High Water dictate when you can arrive or leave.

In the western Channel, and especially in the Gulf of St Malo and the southern Channel Islands, the tidal range is huge, but this is an opportunity rather than a problem because Low Water levels, particularly at neaps, can be several metres above Chart Datum.

Camaret has visitor moorings, pontoon berths and a supermarket close to the harbour. Credit: Ken Endean

That means that the locals are quite relaxed about sailing over foreshores and some of the best anchorages, even for lying afloat, are in places where the charts show drying sand.

To take full advantage of these picturesque diversions, we need to be confident in calculating tidal heights.

For the area west of Cotentin, my other suggestion is use of the largest scale charts – preferably in raster format if using a plotter.

SHOM charts, plus tidal calculations, are an invitation to some beautiful anchorages, like this quiet spot in Isles Chausey when you sail to France. Credit: Ken Endean

A lot of close-in exploration around Brittany consists of sailing between prominent rocks and over areas of sand.

The French SHOM charts are based on surveys that carefully recorded the outlines of rocky patches, and many of their sheets are at a larger scale than the UKHO’s equivalent charts (which are based on the SHOM data).

Digital vector charts for France tend to simplify the foreshore details and when I compared one well-known vector brand with the equivalent SHOM charts it was easy to overlook some of the detailed information, especially when zooming between different scales.

Homeward bound

Sailing back across the Channel, towards a familiar coast, may be an easier prospect than the outward crossing, but there are a few issues to watch out for.

If the passage starts with a SW wind on the quarter, that is all very well but it usually means a depression approaching from the west.

In a strengthening onshore wind, there are plenty of harbours in Devon and Cornwall that will be safe to enter.

East of the Solent most ports have shallow or drying approaches, or entrances where wave reflection causes chaos.

Newhaven’s long western breakwater shields the river entrance from strong westerlies. Credit: Ken Endean

Newhaven might be the safest option, with a dredged channel for ferries and a long western breakwater.

For sailors returning to the western Solent in rough conditions, the North Channel is likely to be safer than the Needles Channel, with choppy water but usually no big waves.

If we have to return by a fixed deadline, it’s advisable to monitor forecasts in the preceding week while in France and sail earlier if bad weather looks likely to interfere.

Good passage planning includes timing our departure to suit the weather.

Get it right and the homeward leg should be another enjoyable sail.

Then it only remains to plan the next holiday to France – perhaps a longer cruise to South Brittany?

Pick up a copy of Sail the British Isles book from Yachting Monthly

From the makers of Yachting Monthly comes this essential guide to sailing around the UK and Ireland. Every iconic location in the British Isles is covered here, from peaceful ports like Dartmouth to sailing hotspots such as the Isle Of Wight. Perfect for planning a long weekend getaway or an ambitious break on the waves, Sail The British Isles is perfect for any boating enthusiast who is itching to discover their next adventure.

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.