Once you’ve experienced the beauty and peace of sailing in the Arctic, you’ll want to return again and again. Andrew Wilkes explains how to make the dream a reality

Sailing in the Arctic can easily become an addiction, writes Andrew Wilkes.

It can start with a night spent at anchor in a remote and beautiful Scottish loch – basking in a clear starlit night in sheltered waters.

You may have spent all day negotiating tidal gates, reefing and shaking out reefs, dodging rocks and using transits. You may even have spotted a sea eagle.

Things might not have gone entirely to plan but you and your sailing partner have solved the problems along the way.

You’re tired, in a very contented way, and you might have a glass of something in your hand.

Andrew Wilkes’ Annabel J sailing in Scoresby Sund, East Greenland. Credit: Andrew Wilkes

The conversation flows and the old subject returns: where shall we go next year?

There are several sensible answers to that question: the Spanish Rías or a cruise in the Mediterranean are good, safe, options.

But… if the romance of your tranquil anchorage has taken a firm grip, you could find yourself at the boat show buying a pilot book for the Faroe Islands.

Winter evenings might be spent at the kitchen table making a passage plan ‘just for fun’.

Then, since you’ve made the plan, you might as well make an attempt at the passage.

One thing leads to another and, in a few years’ time, you find yourself sailing through the icebergs in Disko Bay.

That’s when you know you’re hooked.

The Faroe Islands

Kalsoy Island, Faroe. The northern islands have huge ridges and long fjords. Credit: Ivan Kmit/Alamy Stock Photo

Also known as Føroyar (the islands of sheep), the Faroe Islands are a group of 18 islands with many holms and stacks.

They are about 200 miles north of the Butt of Lewis and boast some of the most spectacular scenery in northern Europe.

Most of the land lies at between 300m and 800m which rises as sheer cliffs from the sea.

The more dramatic cliffs are on the west and north coasts and there are tremendous ridges and fjords in the Norðoyar (northern islands).

The eastern coasts of the central and southern islands are gentler and are deeply indented by fjords.

Strong tides rip through the islands creating eddies and overfalls.

Iceland

Iceland, a land of volcanoes and small fishing towns, it not for the faint hearted but offers rich rewards. Credit: Zoonar GmbH/Alamy Stock Photo

Iceland lies 250 miles northwest of the Faroe Islands. It is a land of volcanoes, icecaps and spectacular geysers.

The lunar landscape created by volcanic action is hard and unforgiving.

Visiting yachts berth alongside tyre-clad quays in small fishing towns.

There are not many people but there is a great sense of Viking history about the place.

Western Fjords, Iceland. One of the remotest regions of the country, jutting out in the Denmark Strait. Credit: Sunpix Travel/Alamy Stock Photo

Thor, Odin and the Sagas rub shoulders with Eirikur Rauði (Erik the Red). Greenland (Kalaallit Nunaat or Grønland) is the world’s largest island but with a population of just 56,000, it is also one of the most sparsely populated places on Earth.

Everyone lives on the coast, mainly the west and southwest coasts. 80% of the land is permanently covered in ice.

Glaciers calve icebergs into the sea which are swept down the east coast, around Kap Farvel in the south, up the west coast and around Baffin Bay.

Kap Farvel is the ‘Cape Horn’ of the northern hemisphere – its storms and vicious weather deserve the greatest respect.

Much of the coast is protected by offshore islands, which creates a magnificent cruising ground.

In the summer, it remains light continuously.

Baffin Island

Baffin Island, Canada. Samford Fjord, in the northeast of the island, enjoys 24 hours of daylight in the summer. Credit: Albert Knapp/Alamy Stock Photo

Baffin Island is the second biggest island in the northern hemisphere. It is rarely visited by yachts.

Much of our pilotage information is based on the old whalers’ observations from the 1800s and early 1900s.

Distances between anchorages are great, tides strong and ice plentiful.

Nature is all powerful and polar bears abound.

The first time we sailed there, I naively thought that, because a place had the word ‘harbour’ in its name then it would offer some shelter, but this is not necessarily the case!

The Northwest Passage

Crew need to be confident to handle heavy weather when sailing in the Arctic. Credit: Maire Wilkes

For better or worse, this is on many sailors’ ‘tick list’.

It is defined as the sea route, north of North America, which connects the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

It is blocked by ice for most of the year but global warming is taking its toll.

It was first transited by Roald Amundsen in 1906. By December 2020, 314 transits had been completed. Over half of these were completed in the last decade.

However, despite what you may read in the papers, ice can still be abundant and a successful transit is by no means guaranteed.

The remoter areas have no facilities of any sort.

Visiting sailors need to be totally self sufficient in every respect with regards to fuel, food, water, spares and maintenance.

The reward you get from this independence is a massive sense of achievement, the privilege of being in some of the most beautiful places on Earth, an almost spiritual connection with nature and, occasionally, meeting the most genuine people.

Sailing in the Arctic: The boat and her equipment

The first challenge of a cruise in higher latitudes is to get there. The boat needs to be seaworthy and comfortable for the delivery voyage.

Good, and free, guidance for choosing and equipping offshore sailing boats can be found in World Sailing’s Offshore Special Regulations (OSR).

Metal hulls are best when sailing in the Arctic as they are generally stronger and cope better with ice. Credit: Danita Delimont/Alamy Stock Photo

They are designed for yachts competing in offshore races but the advice holds good for cruising yachts.

The OSR are split into different categories ranging from short warm weather races (Cat 4) to trans-oceanic races in the world’s most hostile conditions (Cat 0).

Voyages to higher latitudes will fall within the Cat 1 or Cat 0 categories.

Weather can change rapidly and become violent when sailing in the Arctic. Credit: Bob Shepton

When you have arrived at your cruising ground there will be new challenges.

Depending on the area, these might include: poor charting, cold and windy conditions, ice, poor shelter and little or no shore facilities.

A new, and also free, resource is available in the form of the Polar Yacht Guide (PYG) which can be downloaded from the RCCPF or World Sailing websites.

You need to be familiar with your engine, and have the ability to repair it by yourself. Credit: Aleksandrs Tihonovs/Alamy Stock Photo

As the name implies, the guide specialises in best practice for high latitude cruising.

It focuses on safety and the environment. It is very difficult to translate all this into a definitive specification for a high latitude cruising yacht.

There have been some amazing voyages in small, comparatively modest, boats by people like W.H. Tillman, Willy Kerr and Bob Shepton, but I would urge high latitude sailors to consider the following…

- The right hull design and material: Greenland and the Canadian Arctic have extensive coastlines and archipelagos which are not frequented by shipping. There is little commercial incentive to survey and chart the waters with a high degree of accuracy. In these areas, running aground, possibly at speed, is a probability. A modern lightweight hull sitting on top of a high-aspect fin keel is unlikely to take this well. A metal boat will withstand a sudden impact better than most GRP hulls.

- Heavy-weather rigging: A strong and well tested rig with which the crew are familiar. Good, simple reefing systems and storm sails.

- Anchor and chain: Unpredictable katabatic winds are likely. Excellent ground tackle comprising a choice of heavy anchors and lots of chain are recommended. Anchors have been lost in bad weather or ice conditions so spares are vital.

- Protection and comfort: Crew who are over-exposed to cold and harsh conditions are not safe. Think about doghouses, cuddies and heating.

- A reliable engine: Ensure your crew are familiar with the boat’s engine and have a well thought out supply of tools and spares needed to fix

the engine if it runs into problems. - Simple systems: Plumbing, heating and electrical systems which the crew can repair with spares they have on board. You need to be fully self-reliant, and a broken down system that you are unable to repair yourselves could make the voyage uncomfortable or a serious danger to you and others.

- Safety Equipment: Even with the latest communications equipment, boats in high latitudes can be several days away from potential help. Crews need to be capable of surviving in hostile conditions for a long time. Read the Polar Yacht Guide.

The crew: are you ready?

Having a well-prepared crew with adequate experience is essential for sailing in the Arctic. Credit: Bob Shepton

Sailing in the Arctic attracts all sorts. Many go because they want to explore beautiful cruising grounds and build on their experience.

Unfortunately, it also attracts ‘Adventurers’ whose egos exceed their abilities. These people are a danger to themselves and others.

They also give the rest of us a bad name. More about this later.

Courses and qualifications help us to acquire a basic understanding of skills but they are not a substitute for experience.

You need to know your boat, your crew and yourself. Happily there is a great way of doing this – go sailing!

Train for using safety equipment, including survival suits. Credit: Andrew Wilkes

Gain experience in your home waters, get some offshore passages under your belt and fix things yourself.

Start going further afield: spend a season or two on the west coast of Scotland or Ireland.

Then expand your horizons a bit: cruise to the Shetland Islands, the Faroe Islands, the Norwegian fjords and then circumnavigate Iceland.

These are all fantastic cruising grounds which are both beautiful and challenging.

I helped to write the Polar Yacht Guide and, as part of that process, we asked experienced high latitude sailors for contributions.

Members of the Irish Cruising Club have a lot of experience sailing in the Arctic.

This is what they said:

‘High-latitude experience and dedication are both really important.’

‘The skipper must have good people-handling skills along with a high dose of empathy.’

‘Crew compatibility is very important along with plenty of old-style, marina-free, cruising experience in demanding weather and anchoring conditions.’

A Refleks diesel heater keeps life comfortable on board. Credit: Andrew Wilkes

‘It’s essential to have ocean and coastal experience – even if they have no experience in Arctic regions. People with sea miles under their belt understand

how to eat, sleep, work and behave in challenging conditions and can engender confidence.’

‘A physically strong crew is required to pole aside bergy bits in leads’.

‘Have someone on board with good medical skills together with a first-class medical and dental kit.’

Careful planning can help. Much like parenting, the wisest course of action is often to ‘pick your battles’.

Here are a couple of scenarios:

- A voyage from the UK to Iceland could be broken in the Faroe Islands. Each leg would be about 250 miles, or about two days’ sailing. Weather forecasts for two or three days are generally pretty accurate and, provided time is available to wait for a good forecast, a passage in favourable conditions should be achievable.

- Sailing directly to western Greenland from Ireland is a voyage of about 1,200 miles, a week or two’s sailing for an average cruising boat. If ice conditions are unfavourable, a longer passage further north up the west coast of Greenland will be necessary. The weather off Kap Farvel, on the southern tip of Greenland, is often extreme and it can change quickly. By the time a sailing yacht is in this area, the forecasts downloaded before departure will be out of date.

Sailing in the Arctic: Navigating in ice

Ice and icebergs are plentiful in Disko Bay, West Greenland. Credit: Sergey Oyadnikov/Alamy Stock Photo

People sometimes have the perception that global warming is melting all the ice so a small boat passage through, say, the Northwest Passage is easy.

This is too simplistic: global warming is melting the ice and there is a lot less ice than there was 20 years ago but there are still ‘good’ ice years and ‘bad’ ice years.

There are long-range ice forecasts but we don’t really know what kind of year it is going to be until the navigation season has started. 2018 was a ‘bad’ year and only three vessels managed to transit the Northwest Passage.

Ice arches are quite common – do not be tempted to go through them in a dinghy – they do collapse. Credit: Maire Wilkes

2017 was a ‘good’ year and there were 32 successful transits, 22 of which were made by yachts.

Navigating in these waters requires both good planning and luck.

There are a couple of important things you probably already know about navigating in ice: only a the tip of the iceberg is above the surface and a cubic metre of ice weighs a tonne. So a yacht of, say, 10 or even 50 tonnes is not going to smash through much ice.

We have to navigate around it and this determines where we can go. We study ice charts and try to avoid areas showing more than 3/10 ice.

Don’t try to navigate in areas with more than 3/10 ice coverage. A long pole can be helpful to push aside smaller floes. Credit: Jonathan Sumpton/Alamy

However, ice charts, like weather forecasts, are not always entirely accurate and they do go out of date.

Navigation in ice is covered in more detail in my book Arctic and Northern Waters and also in High Latitude Sailing by Bob Shepton and Jon Amtrup.

Much useful information can also be gleaned from reading the Polar Yacht Guide and the Canadian websites which are written for ships navigating in polar waters.

(https://www.ccg-gcc.gc.ca/publications/index-eng.html).

Things to consider when sailing in the Arctic:

- Know how to use ice charts to find out which waters are navigable.

- Wind and current will move ice. Use weather forecasts in conjunction with ice charts to forecast ice movements.

- Anchor watches are necessary to avoid being hit by ice

- Fog and ice often go hand in hand.

- Fuel consumption will be increased whilst navigating in icy waters.

- Learn traditional techniques such as spotting open water leads, ice blink and water skies.

- Ice shelves often protrude from an iceberg or ice floe beneath the surface – do not go too close.

- Icebergs and glaciers often ‘calve’ without warning. Decide on safe distances from icebergs.

- One or two ice-poles are useful for pushing away small floes.

- Radar may detect icebergs but will probably not smaller bergs or flat floes.

- Ice accretion on a vessel will affect her stability as well as the operation of mechanical equipment, electrics and antennas.

Impact on the environment

An Arctic fox in its darker summer coat – one of numerous species to be spotted while sailing in the Arctic. Credit: Rodger Grayson and Ali Dedman

The days of ‘attempting a transit through the Northwest Passage to highlight global warming’ are gone.

We all know global warming is happening and, if we are honest with ourselves, we should know that our presence sailing in the Arctic is not helping.

If we choose to sail there, we should make it incumbent upon ourselves to minimise our impact on the environment.

A polar bear swims around the boat at Beechy Island. Credit: Maire Wilkes

We sail there because we love nature, so it should not be difficult to convince ourselves that we should do our best to protect it.

Environmental considerations

- The Arctic has one of the world’s most fragile ecosystems.

- The short Arctic growing season means that plants grow at a very slow rate.

- It is home to some of the world’s most endangered species.

- Cold temperatures slow down or stop the decomposition of organic matter.

Vessels visiting the Antarctic have to obtain a Permit. This requires a high degree of planning including a boat specific Environmental Impact Assessment.

While there are many regulations designed to protect the Antarctic environment, at present little legislation applies to the Arctic and it is left to skippers to act responsibly.

Responsible Arctic cruising

A hunter in Qinngertivaq Fjord, eastern Greenland. Credit: Jonathan Sumpton/Alamy Stock Photo

Detailed guidance is given in Arctic and Northern Waters and in the Polar Yacht Guide. This includes:

- Responsible engine, generator and outboard maintenance

- Fuel transfers

- Dealing with oil and fuel spills

- Boat maintenance

- Trips ashore

- Management of rubbish and waste disposal

- Black and grey water disposal

- Biosecurity and minimising the risks of introducing invasive species

- Responsible behaviour at historical sites

- Respecting local people and their culture

- How to minimise our disturbance to wildlife – ashore, at sea and in the air

The Polar Yacht Guide includes an example of a boat specific ‘Environmental Protection Plan’.

Every boat will have different limitations and resources, so skippers must develop their own boat code of best practice.

Make a plan for sailing in the Arctic

If you have not sailed in high latitudes before, and I haven’t dissuaded you from doing so, you need to make a plan.

Remember Roald Amundsen’s advice to foresee and prepare for every difficulty, read all you can and get as much experience as you can.

Be a Seaman not an ill-prepared ‘Adventurer.’

The author’t boat sailing in Scoresby Sund, East Greenland. Credit: Maire Wilkes

You will need a boat and you will need to equip her. Like most sailing projects, this can either be done expensively or very expensively.

It is unlikely to be done cheaply but, if you are committed, it is probably achievable.

You can read accounts of, mainly, successful high-latitude cruises on the web pages of sailing clubs like the RCC, OCC and Trans-Ocean.

I gave a talk recently about sailing in the Arctic which was followed by a number of mainly very sensible questions.

Continues below…

A guide to high latitude yachts

Yacht cruising within the Arctic Circle has become increasingly popular, but what is the best type of yacht for the…

Roger Taylor: Impossible voyage conquered

Roger Taylor navigates his engineless 24ft Mingming II on a 4,000 mile nonstop voyage around the usually icebound waters of…

Heavy weather sailing: preparing for extreme conditions

Alastair Buchan and other expert ocean cruisers explain how best to prepare when you’ve been ‘caught out’ and end up…

Adventure: guide to sailing in storms

Award-winning sailor and expedition leader Bob Shepton regularly sails some of the most storm-swept latitudes in the world. Not bad…

The question which floored me came from a relatively inexperienced listener who asked: ‘How much would it cost me to equip a boat and sail through the Northwest Passage?’ He had totally missed the point.

Sailing in these waters is not about money, the size or sophistication of your boat.

It is not even about the training you have done or the safety equipment you might have on board.

Greenland’s capital Nuuk is a good option for resupply and crew changes when sailing in the Arctic. Credit: Niels Melander/Alamy Stock Photo

What is important is the experience you have gained before moving on to the next stage of your sailing career.

Enthusiasts will read everything they can about the subject at hand, learn from anyone they can and practise their skills until they become second nature.

If you do this, and are honest with yourself, you will know if the boat, the crew and you are ready.

Successes and failures

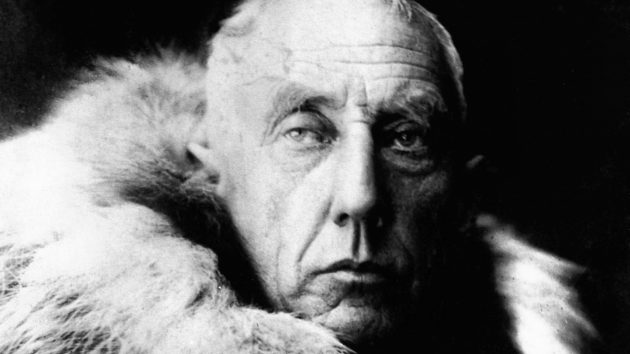

Roald Amundsen, the Norwegian who led the first successful transit through the Northwest Passage famously wrote, ‘I may say that this is the greatest factor – the way in which the expedition is equipped – the way in which every difficulty is foreseen, and precautions taken for meeting or avoiding it. Victory awaits him who has everything in order – luck, people call it. Defeat is certain for him who has neglected to take the necessary precautions in time; this is called bad luck.’

He completed the transit in 1906 but his advice is as relevant today as it ever was. Some have followed it and others have not.

I am not sure if the Franklin expedition should be counted as a success or a failure.

Roald Amundsen who led the first successful voyage through the Northwest Passage. Credit: GL Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

Much has been written about Sir John Franklin’s 1845 expedition to find the Northwest Passage.

His two ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror and 134 officers and men were lost in the ice off King William Island.

The British, however, have a unique talent for remodelling apparent failures into resounding successes.

The expedition prompted a huge interest in Arctic exploration and much was learned from the expeditions which followed this one.

Roald Amundsen was a smart Norwegian cookie.

Not for him the grandeur of the Royal Navy. Despite not having a 1,000-book library, extravagant dinner services, dress uniforms, and highly polished brass buttons, he transited the Northwest Passage for the first time in 1906.

Amundsen transited the Northwest Passage in an old herring boat with a crew of six men. Credit: Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

He did it, over a period of three years, in a converted herring fishing boat with six men dressed in Inuit seal-skins.

My wife, Máire, and I were moored alongside in Nuuk, the capital of Greenland in 2008.

A 32ft yacht, with a broken boom, tied up alongside us. We invited the two crew onboard and they told us their story.

The owner/skipper was very ‘gung-ho’ and rather full of his and his boat’s prowess. The other man was very quiet.

I think he was still in a state of shock following their recent ‘adventure’.

They had been knocked-down that day whilst sailing in bad weather, the boom and sails were in pieces.

The crew had been washed over the side but had managed to clamber back onboard. The boat and her contents were soaking.

We gave them a hot meal and dry sleeping bags.

The crewman flew home the next day and I often wonder what became of the skipper.

Adventurers vs Seamen

In 2013 a group of American adventurers, who featured in a US reality TV show called Dangerous Waters, attempted to use jet-skis to transit the Northwest Passage.

Andrew Wilkes has cruised all his adult life. He and his wife cruise Annabel J, a 56ft gaff cutter, in remote areas such as the Baltic, Alaska and Chile

Their tent was torn up by a polar bear and the jet-skis did not work when the sea started to freeze.

They and their support/fuel boat were rescued by the Canadian Coastguard.

The rescue expedition is reported to have cost a six-figure sum.

The yacht Anahita, an Ovni 345, was crushed by ice and sank in the approaches to the Bellot Strait in 2018.

The Canadian Coastguard had warned yachts away from the area four days before the incident. Fortunately the crew were rescued.

On a positive note, the number of people sailing in high latitudes is increasing year on year.

Nearly all of their passages are successfully completed by competent sailors in well-equipped boats.

Additional information for sailing in the Arctic

Polar Yacht Guide Alan Green, Andrew Wilkes, Victor Wejer & Skip Novak (World Sailing/Royal Cruising Club Pilotage Foundation, free) https://rccpf.org.uk/pilots/187/Polar-Yacht-Guide OR www.sailing.org/sailors/safety/polar_yacht_guide.php

Arctic and Northern Waters by Andrew Wilkes (Imray/Royal Cruising Club Pilotage Foundation, £65)

Buy Arctic and Northern Waters at Amazon (UK)

Buy Arctic and Northern Waters at Amazon (US)

High Latitude Sailing by Jon Amtrup & Bob Shepton (Adlard Coles, £25)

Buy High Latitude Sailing at Amazon (UK)

Buy High Latitude Sailing at Amazon (US)

Buy High Latitude Sailing at Waterstones

Note: We may earn a commission when you buy through links on our site, at no extra cost to you. This doesn’t affect our editorial independence.

Arctic and Northern Waters and NW Passage Periplus: https://rccpf.org.uk/pilots/191/Periplus-to-Northwest-Passage

World Sailing Offshore Special Regulations https://www.sailing.org/specialregs

Canadian Coastguard publications (including the Manual of Ice, Notices to Mariners, Canadian Aids to Navigation): https://www.ccg-gcc.gc.ca/publications/index-eng.html

Few, if any, high latitude recreational cruises took place in 2020-21 due to the COVID pandemic.

At the time of writing (Oct 2021), most Arctic communities do not welcome foreign visitors due to limited resources to cope with potential outbreaks.

It is hoped this will change next year, but contact the appropriate authorities before departing.

Sailing in the Arctic: how to cruise to the far north

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

-

-

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

-

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.