Nic Compton and assorted crew members lock into the French canals as they make their way from the Channel to the Mediterranean

One thing everyone knows about taking a sailing yacht into the French canals is that you have to take the mast – or masts – down first. Yet, while we had got everything else ready – extra fenders, long mooring lines, folding bikes, mast crutches, and even the required navigation qualification – the one thing we had never done was actually take the masts down. This might seem a straightforward procedure, but when you have a 40-year-old boat with free-standing, carbon-fibre masts which have probably never been lowered since she was built, nothing is straightforward.

These were the thoughts going through my brain as the crane in Le Havre tugged on the mizzen mast – 500kg, 600kg, 700kg, 800kg. STOP! By now the coachroof was bulging and the whole boat seemed to be lifting out of the water. Clearly something wasn’t right. The crane eased off. Luckily, the crane operator was a Mini-Transat sailor himself and had lowered and raised countless carbon-fibre masts. Between us, we worked out that the stainless steel plate had to be removed to release the nylon wedge which was holding the mast in place.

Once again the crane lifted – 500kg, 600kg, 700kg, 800kg. STOP! And still nothing happened. Then I jumped on the coachroof, and with a shudder the mast came sliding out and the boat settled back in the water. We could all breathe again. Now we knew what we were doing, the main mast came out much more easily, and two hours (and 200 euros) later, both masts were sitting snugly on their wooden crutches. We were back in business.

Cruising along the Canal du Loing. You borrow a remote control to pass the series of automated locks. Photo: Nic Compton

It was a hugely symbolic moment in our 1,800-mile odyssey from the UK to Greece. After a breezy 163-mile ride up the English Channel, we had arrived at the ‘embouchure’ –

the point at which our Freedom 33 Zelda would be turned from an ocean-going yacht into an inland creature.

I was glad to have ‘the boys’ (my friends Matt and Laurence) on board for this part of the voyage, not just for the boisterous Channel crossing but for the stressful mast-lowering. My wife Anna and the kids would take their places once we reached Paris for what we hoped would be the more relaxing bit: meandering through the French canals.

Up the seine

Two days after taking the masts down, we found ourselves heading up the Seine. More by luck than planning, we had timed the tides just right for the 65-mile trip from Le Havre to Rouen, which has to be completed in one hop, in daylight hours and on an incoming tide.

It was a good 11-hour passage to the beautiful city of Rouen, bustling with students, where we enjoyed a couple of rounds of absinthe at a trendy bar just a few metres from where Joan of Arc was burned at the stake. History is never far away in France.

The River Seine up to Paris is an impressive waterway: wide and majestic. When we went up it in May, there was considerable commercial traffic and no other pleasure boats whatsoever. The locks were equally impressive and clearly geared towards commercial shipping. The bollards were spaced too far apart for us to tie off between two, so the only option was to put a pair of springs on a single bollard and use the engine to bring the bow in or out. It takes a bit of getting used to, especially as you have to keep moving the lines to the next bollard up as the boat lifts with the incoming water, but it was nowhere near as bad as the horror stories I’d read online.

Our rendezvous in Paris was on 24 May, but a burst exhaust manifold nearly scuppered that idea. Luckily, it happened just as we were passing the small marina at Port Ilon, just past Vernon, which had a mobile mechanic on site. Some 36 hours later we were up and running again, thanks to a ‘temporary’ repair by Kamel, which lasted all the way to Greece.

Spectacular arrival

Meanwhile, Anna and the kids were on their way to meet us – had they looked carefully, they might have seen us motoring up the Seine beneath them. And what a spectacular arrival it was, with the golden evening sun lighting up not just the Eiffel Tower but all the decorative bridges – there are 37 in all – as we wound through the heart of the city.

Just as we came to the most beautiful part, the Ile de la Cité, with the towers of Notre Dame resplendent before us, there they were, Anna and the kids, waving to us from the bridge – having arrived with less than a minute to spare.

Matt pictured with the Eiffel Tower as we approached Paris. Photo: Nic Compton

We moored at the Port de l’Arsenal, right in the heart of the city, for the princely sum of €37.50 per night – half the price of a cheap room in a hotel. And Paris was the vibrant, friendly place we remembered. The kids loved whizzing along the Seine on rented electric scooters to visit the Eiffel Tower, and Anna had a nostalgic moment visiting her old haunts at the Jardin des Plantes, just opposite the marina.

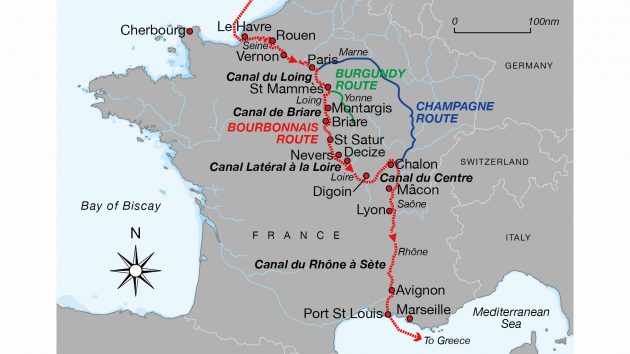

From Paris, there were several options for going down the canals. We could turn left and go down the Champagne Route, or we could turn right towards St Mammès and, once there, either head due south down the Canal du Loing, known as the Bourbonnais route (longer but fewer locks), or southeast along the River Yonne, the Burgundy Route (shorter and prettier but more locks). We opted for the Bourbonnais, which we’d heard was a bit deeper and less likely to silt up.

The fascinating approach to Paris on the River Seine. Photo: Nic Compton

Locked on

That route took us up the Seine up past the Forest of Fontainebleau – where we swam in limpid water – to St Mammès, a small backwater town which, like most of the places we visited in what was evidently the off-season, was practically deserted.

There, we were equipped with an electronic device which we used to open the automated locks as we approached. Once inside, we operated the locks ourselves by pulling a blue cord set into one side of the lock. A red emergency cord stopped the process.

We enjoyed the autonomy of managing the 18 locks ourselves, as we wound through bucolic countryside and pretty rustic villages, which we had mostly to ourselves. Most of the canals had cycle paths, so Anna and the kids took turns on the two folding bikes we’d brought along. The Canal du Loing was followed by the Canal de Briare, which had another 32 locks, so that by the time we got to Briare itself we had negotiated 50 locks in five days. Only another 130 to go!

The spectacular aqueduct over the Loire at Briare. Photo: Nic Compton

From Briare, we crossed the magnificent canal bridge designed by Gustave Eiffel which crossed over the Loire to the Canal Lateral à la Loire (196km for 38 locks). This was supposed to be the fast part of the journey, but with weed clogging up the waterway, forcing us to stop to clear the engine’s water filters and cut weed from around the propeller, we got bogged down. We were told that the lack of traffic during the pandemic meant the weeds had grown up, and indeed our depth sounder regularly showed 1ft and under, even dropping to 0ft at times – an alarming prospect for any salt water sailor!

This was prime wine country, and at St Satur we walked up through the vineyards to the fortified town of Sancerre, where we bought bottles of the local Sancerre and Pouilly-Fumé wines. That night and the following night at Nevers, there was a lightning storm that lit up the sky and cracked with a terrifying loudness right over our heads. It was a remarkable display and we thought nothing more of it until we got to Decize two days later and heard that 100 trees had fallen into the canals ahead. The French canal authorities, Voies Navigables de France, estimated it would take three days to clear the debris.

Near Ciry le Noble after being chased out of town by fishermen. Photo: Nic Compton

Thanks to those fallen trees, it took us over a week to get through the Loire canal, followed by another four days through the Canal du Centre (114km for 61 locks). By the end, we were clipping along doing more than a dozen locks a day – our best run was 26 locks in one day.

Downhill finish

Two and a half weeks after leaving Paris, we reached the ‘summit’, with the Océan lock behind us leading back to the English Channel and the Méditerranée lock ahead of us heading to the Med.

We were 620ft above sea level and it was all downhill from now on, which made the locks much easier to handle. And then, one fine day, we slipped out of the giant 35ft deep Lock 34b onto the wide expanse of the River Saône. I breathed a sigh of relief as Zelda was swept down the river and we no longer had to worry about hitting things – we had already bashed the port side coming into one lock and gouged the starboard side going out of another. It was also getting increasingly hot and it made all the difference to be able to swim in the river – something that was forbidden in the canals.

Nic’s daughter on deck as we approach Chalon on the River Saône. Photo: Nic Compton

After the quiet of the past two weeks, we loved being on the more open waters of the Saône. The towns were bigger and busier. We loved prosperous Chalon and the more down-at-heel Mâcon where there was plenty to keep the kids amused.

It took three days motoring down the Saône before we reached Lyon, where we had arranged our next crew change. Once again, we had located a fantastic small marina close to the city centre – the Confluence Marina, with just a dozen yacht berths – where we were able to leave Zelda at a cost of just €16 per night, while we all flew back to England.

Back in town

Two weeks later, I returned with ‘the boys’ (three of them this time: Laurence, Matt and James) for the final leg of the voyage: the 310km from Lyon to Port St Louis, at the mouth of the Rhône. By then it was early summer and the river was no longer in full spate. A gentle current helped us on our way, and we made fast progress through the huge locks.

After three days’ motoring, we reached the sea. It was thrilling to go through the final lock and sit in salt water again, and even more thrilling to get the masts back up the following day, ready for the next stage of our voyage: the 900 miles from Port St Louis to Greece.

It had taken us a month (excluding the ‘down time’ in Lyon) to cross France, from Le Havre to Port St Louis. It certainly wasn’t a normal relaxing holiday – for that, I’d recommend hiring a boat, visiting a small section of canal and allowing plenty of time to savour the culinary and visual delights – but it was certainly an experience each one of us will always remember.

Enjoyed reading this?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

-

-

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

-

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.