Remote and challenging, Easter Island and Pitcairn do not feature on many cruisers’ itineraries. Yet for Ivar Smits and Floris van Hees, they were obvious stopovers crossing the South Pacific

Easter Island (or Rapa Nui) is the most remote inhabited island in the world. Sailing there confirmed it for us. True, we took a detour, sailing north for a few days from Robinson Crusoe Island because a high-pressure system was blocking the direct course. By circumventing this windless area, we hoped to reach the zone where easterly trade winds would blow us westward. Yet for the first few days, light southerly winds barely filled our gennaker. With a daily average of 80 miles our progress was slow, but the calm seas provided comfort on board.

Just when we reached the latitude of the trade winds, the wind abandoned us. Frustrated, we lowered the light-wind sail to avoid damaging it. Drifting, we waited for wind. Our patience was tested for several days, before the reward finally arrived in the form of steady winds propelling us westward. Surrounded by nothing else but different shades of blue, each sign of life attracted our attention. A curious albatross flew around our boat, Lucipara 2. Small, agile birds skimmed the surface to feed. At night, the sky was dark yet so clear we could see the Milky Way all the way to the horizon.

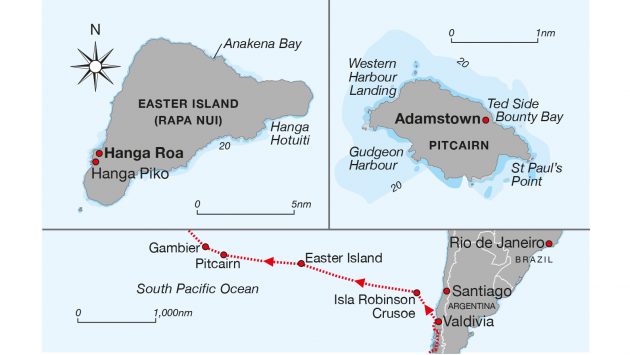

After 18 days and more than 2,100 miles, our anchor finally dropped in front of Easter Island’s main town, Hanga Roa. We were relieved. It marked the end of our circumnavigation’s longest passage so far.

Finding the island was easy thanks to GPS and nautical charts. It’s hard to fathom how the original inhabitants discovered this tiny dot in the vast Pacific Ocean. Research suggests that Polynesians landed here around 1100AD after sailing thousands of miles on a catamaran, a replica of which we admired on land. Contact with the outside world only occurred six centuries later, which underscores how remarkable the first settlement was. Our challenge was avoiding breaking waves as we went ashore from the anchorage.

Finding traces of the original inhabitants was easy. Large stone statues, moai, are everywhere, some 10m high and weighing many tonnes. The islanders built the moai to cherish the mana – the power and wisdom – of influential ancestors. Over time, the moai were made ever larger. It took an increasing amount of manpower to construct them and a lot of wood for their transport. The islanders also used wood for shipbuilding and fire, which made the material even scarcer. Stowaway rats did the rest. With tree seeds and bird’s eggs as their favourite diet, they contributed to the complete deforestation of the island and the extinction of almost all land birds.

Floris looks happy to sight Easter Island after several weeks at sea. Photo: Ivar Smits and Floris van Hees

The ensuing ecological crisis made it increasingly difficult to build seaworthy vessels for fishing and to transport the moai. Social unrest arose and the production of moai abruptly stopped.

Rat meat diet

Yet the misery caused by ecosystem destruction is only part of the story. The islanders were able to adjust their diet and farming methods. Archaeological research shows that they ate fewer birds and fish but more shellfish and rat meat. As deforestation increased, the fertile soil eroded and the wind got a grip on crops. In response, the islanders built stone-encircled gardens. That explains why the islanders were well-fed and cheerful, according to the report of the first meeting with outsiders on Easter Sunday 1722.

During this ‘acquaintance’, at least 10 islanders were reportedly shot dead. Later contacts with outsiders turned out to be even more disastrous. Slavery and introduced diseases reduced the original population from several thousand to just 110 in 1877.

Moai – memorials to important ancestors – are everywhere across Easter Island. Photo: Ivar Smits and Floris van Hees

Today, Easter Island is a holiday destination, meaning that its inhabitants depend on cheap fossil fuels to transport tourists and goods by air and ship to their island. Yet we also met locals striving for a more sustainable island society. All of them were inspired by their ancestors’ mana and values and launched initiatives for more self-reliance and better protection of the environment.

These ranged from growing their own food, setting up a packaging-free supermarket, lobbying for the designation of marine protected areas, organising beach cleans, stimulating bicycling on the island, and teaching children traditional music, culture, and organic gardening in an eco-school. The government did its part by growing trees to reforest parts of the island.

Throughout our three weeks there, we checked the weather forecast daily, as we knew that a shift in wind or swell meant that we would have to move. As it remained calm, we also witnessed the annual Tapati festival. This most important event of the year celebrates folklore, music, dance, and sports and was a delight to attend. Only when our Chilean visa ran out were we forced to abandon this unique island and set sail to its closest neighbour, Pitcairn.

Lucipara 2 (Luci) arriving at Pitcairn Island. Photo: Ivar Smits and Floris van Hees

Bounty Island Pitcairn

Once again, light winds plagued us on our passage. They were just strong enough to keep the gennaker full, although sometimes we needed to hand-steer to make any progress. Our efforts paid off: just before the 14th sunset and on the last breath of wind we reached the illustrious Pitcairn. In very calm conditions we dropped our anchor in Bounty Bay. With no wind and just a little swell, the circumstances were ideal for landing on this island, notorious for lacking sheltered anchorages.

The island was made famous by the mutiny on the HMS Bounty, a transport ship of the Royal Navy. In 1789, mutineers under the command of Fletcher Christian took control of the ship and ejected Captain Bligh and crew loyal to him onto a sloop.

Luci anchored in Bounty Bay, Pitcairn. Photo: Ivar Smits and Floris van Hees

The mutineers, afraid of the long arm of the British authorities, looked for a remote and uninhabited island to which they could flee, along with women they picked up in Tahiti. Pitcairn was the ideal hideaway. It was not along shipping routes and had a rugged coastline. To make sure no one would find them, they burned the Bounty in the very bay where we anchored. Even these days Pitcairn is very remote. There is no airport, so it is only accessible by private yacht or transport ship. Somewhat ironically, the island is now a British Overseas Territory. Nevertheless, after we safely landed our kayak on shore, the welcome sign proudly pointed out that it is the home of the descendants of the Bounty mutineers.

On the quay, officials enthusiastically welcomed us with necklaces made of shells and information brochures. After filling out a form, our passports were stamped, twice. Once for our arrival and once for our departure. ‘You can fill in the date yourself,’ immigration officer Brenda Lupton-Christian (a descendant of Fletcher) explained. ‘If the weather deteriorates you might need to leave and won’t be able to come ashore.’ Now that’s a sailor-friendly approach, we thought! ‘Come by my house if you feel like it,’ she mentioned as we set out to explore the island on foot.

The impressive Polynesian catamaran replica on Easter Island. Photo: Ivar Smits and Floris van Hees

As we hiked uphill, the steep and rugged coastline of volcanic rocks gave way to trees, flowers and birds. Nature really seemed to rule outside the island’s only settlement, Adamstown, because its 50 residents take up little space. Never mind that we didn’t bring food with us: we picked fruits that grow in the wild, such as bananas, guavas, passion fruit, and avocados. Coconuts were also up for grabs under palm trees. What a feast after two weeks at sea!

On the south-eastern edge of the island we found a natural saltwater pool between basalt rocks: St Paul’s Pool. Waves regularly broke over the pool’s edges to bring in fresh water and sometimes made it impossible to swim. Yet on one of our visits it was serenely calm. We snorkelled in crystal-clear water, surrounded by colourful fish that ignored our presence. ‘I feel like I’m in an aquarium!’ Floris mumbled through his snorkel.

On our way to Brenda and her husband Mike, we passed vegetable gardens filled with pumpkins, tomatoes, lettuce, cucumbers, and melons. ‘The supply ship only comes four times a year, so we grow a lot of fruit and vegetables ourselves,’ Mike explained.

For the residents of Pitcairn, it comes naturally to help each other. ‘We are a close-knit community,’ Brenda explained. ‘Everyone has multiple roles and we all have to make do with what we have. After all, we can’t just buy something new.’ As a result, the islanders share things and fix whatever breaks. Consumerism and competition about who has the latest gadget are hard to find here.

A Polynesian outrigger paddle competition during the Tapati festival on Easter Island. Photo: Ivar Smits and Floris van Hees

The highlight of our stay was when we were invited to Brenda’s birthday party. We met most of the Pitcairners there and learned that many choose to live here because of the sense of community. Their biggest challenge is convincing others to make the island their home, as the islanders are getting older and young people are seeking their fortunes elsewhere.

Another challenge was waste. Although the islanders try to keep waste to a minimum, some still arises from packaging of imported food and goods. Mike explained that the garbage was separated in different-coloured bins. Organic waste is used as compost for vegetable gardens, while souvenirs are made from glass bottles. Plastic is ground into small pieces and mixed with concrete to pave roads. Cans are put on the supply ship to be taken back to New Zealand for recycling. That’s why the island is spotless.

Luci rocking at the anchorage in Bounty Bay. Photo: Ivar Smits and Floris van Hees

Self reliance

After a week of calm weather, the easterly wind picked up again. While a cruise ship arrived and the Pitcairners got ready for the influx of tourists, we hoisted the gennaker and set sail for the Gambier Islands. Behind us the waving residents got smaller.

We realised that the Pitcairners’ self-reliant way of life offers important sustainability benefits in terms of nutrition and the re-use of materials, and drew parallels with Easter Island. There, the islanders’ ancestors experienced that their survival depended on cooperation and healthy ecosystems. At the same time, they were resourceful and able to adapt.

The anchor from HMS Bounty. Photo: Ivar Smits and Floris van Hees

Easter Island nowadays shows that the road to a more sustainable society is not easy, with the growing tourism sector and consumer society putting a heavy burden on the islanders’ self-reliance and natural resources. Nevertheless, meeting sustainability frontrunners that are inspired by the spirit of their ancestors strengthened our conviction that the community is making encouraging progress towards a more sustainable future. It reaffirmed that our future is not written in stone but depends upon our own behaviour.

It is up to all of us to apply positive, workable solutions and to make choices in which both nature and humans thrive. These are perhaps the most important lessons that we came away with from our time at Easter Island and Pitcairn.

Just as these islands form oases in the vast Pacific Ocean, our living planet – our home – is isolated in the endless universe. We need to safeguard it for our own survival.

Enjoyed reading this?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

-

-

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

-

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.