Guy Clegg and his family spent over two months cruising north through the outer Hebrides off the west coast of Scotland, discovering remote, enchanting islands

Sitting at anchor was a pattern we were becoming accustomed to – waiting out one or more low pressure systems before having an all too brief respite in which to set sail and explore a more remote, less visited but often more exposed location.

We had been voyaging along the Outer Hebridean chain of islands from south to north for almost two months now and summer had so far eluded us. While the rest of the nation baked in often unbearable heat, we had seldom experienced temperatures in excess of 14°C and it was already mid-August.

On more than one occasion during the preceding weeks, we had positioned ourselves in a suitable location from which to make the westward hop to the famous St Kilda group of islands (110 miles or 180km from the mainland), but repeatedly, at the last minute, the weather window had shrunk or closed altogether.

We were not in the habit of visiting a location for a day and then departing. We liked to explore, get a feel for an area, absorb its atmosphere. It is a yacht’s ability to visit wild and remote locations and then make them our temporary home that has led my family to choose to live an ocean voyaging existence, aboard Free Spirit, our beloved steel, long-keeled, cutter-rigged Koopmans 39.

On board Free Spirit with Guy, Jasmine and Joanna Clegg

While anchored off Berneray, in the Sound of Harris, a small window had opened for an attempt on St Kilda, but a unanimous crew had decided instead to utilise the only predicted two days of consecutive sunshine we had experienced all summer, to relax and explore the white sand beaches and flower meadows of Berneray. We did not regret the decision.

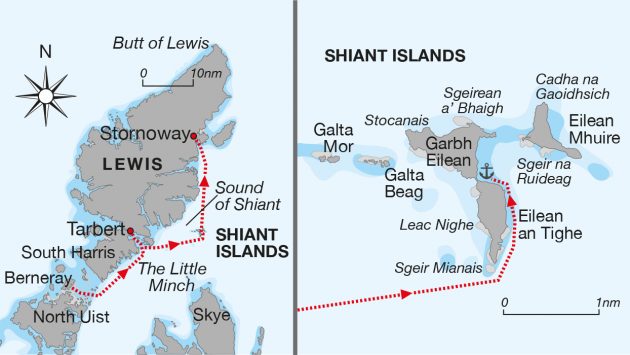

Now we were anchored approximately half a nautical mile south-east of Tarbert, the main community of Harris. The Shiant Isles were to be our next port of call and this time we were resolved to make for our destination – eventually the weather window was sure to open.

The Shiants, a group of two islands with numerous surrounding islets and rock skerries, are uninhabited, but their cliffs, boulder scree margins and turf tops provide the perfect nesting ground for hundreds of thousands of breeding seabirds during the summer months. An estimated two percent of the world’s puffin population is known to breed on the Shiants alongside thousands of shags, razorbills, guillemots, fulmars and kittiwakes.

Though situated in the Minch, only four miles from Lewis and 11 miles from the northern tip of Skye, the Shiant Isles are in an area of strong tidal streams and the few anchorages within the islands are deep and exposed. It is not uncommon for yachts to pass through the islands, but few stay for very long and lunchtime stops or sail-bys, to see the breeding colonies of birds, seem to be the norm.

Basalt columns are home to thousands of birds nests

Three-day window

It was already the second week of August, late in the seabird breeding season. We hoped we were not too late to witness puffins flying with their iconic, bright, sand-eel filled bills. Eventually a three-day weather window was forecast and preparations aboard Free Spirit began in earnest.

Like the film teams of ‘nature diaries’ often shown at the end of David Attenborough’s documentaries, the boat became a busy hive of activity, making sure all camera, drone and phone batteries were fully charged; that camera housing seals were clean and lubricated, that snorkelling gear was at the ready. We also put together a raft, for a lifesize decoy puffin we had purchased, to float on. The day before departure, we pulled in at the small marina in Tarbert to refill our water tanks and replenish food supplies. We were now ready for the next adventure.

We set off early, in winds of 20 knots, to cover the 16 miles to our destination. As forecast, the winds soon dropped to virtually nothing and patches of cold grey mist hung in clouds on the surface of the Minch. We passed storm petrels dancing upon the sea surface, small rafts of puffins, occasional fulmars and dolphins, as we motored on, towards the black silhouettes of the Shiants.

A decoy puffin is launched as the camera team prepares to film underwater

As we neared the southern end of the islands, we were awed by 100-metre high columnar jointing in the basalt cliffs. The sea between the islands was calm and the dramatic black islands rose vertically towards their mist-covered tops producing what felt like an imposing amphitheatre.

We dropped anchor at low tide, in 14m of water, to the east of the low pebble isthmus, between the northern and southern sections of the largest island. Our 25kg spade anchor set decisively and with our full 50m of chain and a further 30m of rope warp, we felt we could relax in this exposed anchorage for the coming days. (Don’t tie on to a lobster pot, as we witnessed one short-stay yacht doing!)

With the engine off and anchoring complete, we spent a long while on deck just drinking in the sights, sounds and atmosphere of this awe-inspiring location. It all felt otherworldly – remote, wild, powerful: a place of raw nature. A sea eagle appeared in front of us, lazily flapping its wide-fingered wings as it searched the cliff line for its next meal. Though the guillemots and razorbills had finished breeding and left, the rocks and cliffs were still alive with birdlife and the scree slopes before us thronged with thousands of juvenile shags, all jostling along the water’s edge in dense groups of shining black.

A natural arch to our north looked out towards the Sound of Shiant and to the east of this, across a 500m-wide, strong tidal gap, began the outline of the second, smaller island, with less imposing cliffs but a smooth covering of vibrant green grass, somehow at odds with the starkness of the basalt beneath.

There is no better way to get close to the unique seabird colonies of the Shiants than in sea kayaks

Early settlements

This setting was to be our home for the next three days and nights, but prior to 1901 these islands had been the home to subsistence farmers and fishermen. There are numerous signs of habitation throughout the islands, a few walled settlements, stone boundaries and ‘lazy beds’ (raised bed field systems) wherever the soil was deep enough.

There is evidence that at one point during the mid-18th century, five families, and up to 40 people, inhabited the island. There is even believed to be the possible remains of a small church and associated graveyard. Now the only usable building is a small cottage-bothy (by permission only), situated just south of the pebble isthmus of the largest island that belongs to the owner of the islands – the celebrated author, Adam Nicolson.

Besides ornithological surveyors, writers and the owner’s friends and family, few people stay on the islands. Crofters from Harris and Lewis run a herd of sheep across the Shiants (there are new herding facilities around the cottage) but they do not stay. By and large, sailors making landfall will have the place to themselves, along with some sheep, a seal colony and, in summer, hundreds of thousands of birds.

Two percent of the world’s puffin population is known to breed on the Shiants alongside shags, razorbills, guillemots, fulmars and kittiwakes

After a bite of lunch we deployed our landing-touring craft – three rigid-frame inflatable kayaks, and set off to explore. It was slack tide, low water and the wind was now non-existent. We took advantage of these perfect conditions and crossed over to the eastern island. Large seals followed in our wake as we entered a cathedral-like cave and then continued around skerries and over kelp-covered reefs along the island’s southern shore. The turf bank above the steep rock was full of puffin burrows and, though many were now empty, there was a constant, mesmerising dance of birds leaving and returning.

View from the summit

We pulled up our kayaks on the most easterly point of the island and found a way up to the flat, grassy, table top, summit. Rarely have I encountered such lush grass and it was a joy to traverse the full 1.5km of the island, across the ancient field systems, sometimes barefoot, gasping at the views across to the neighbouring island, the mainland, Skye and to Lewis. Flocks of geese grazed the grass before us, puffins to and froed, and in the clear waters below, we watched seals hunting. Perfection – if not for the low summer temperatures and the biting Scottish midges – that were out now in force.

Our meandering return paddle that day included a pass through the majestic sea arch we had spotted earlier, from the north to the south. As we passed through, back into the bay of Shiant, we were met with thousands of black juvenile shags, positioned like sentinels before a Tolkien-like, mythical landscape.

It all felt oversized and powerful, an assault on the senses. A rare, white, leucistic shag greeted us at the entrance to this ‘other world’ and added to the sense of mystery, as we paddled back through rafts of birds to our home, Free Spirit.

Enjoying the view west from Eilean Mhuire

We continued our exploration of these strange islands for another two days. At one point my daughter, Jasmine, and her partner, donned their wetsuits and towed the decoy puffin raft from the boat, up the westward shore of the inner bay. Though the puffins were not fooled, rafts of shags surrounded them and they returned joyful and with camera memory cards filled with images of curious birds, both above and below water.

One memorable evening, I rested in the lee of large basalt blocks, while the mist was funnelled to either side, clearing a gap, free of cloud, all the way to that elusive Scottish summer sun. We had just explored the settlement remains on the western side of the southernmost island and, as I basked in the warmth of that sunshine, my mind turned to the people who had lived here long ago. Before becoming a sea nomad together with my family, I had been a tenant organic farmer on a Cornish coastal farm of about the same land size as the Shiants. The grass here was more lush, the basalt soils appeared richer and more productive.

Paddling under the rock arch of Eilean Mhuire

Island life

They would have had potatoes, corn, cabbages, kale, milk, eggs, meat, seafowl, seafood, seal-oil and fresh water from a number of wellsprings. In addition, for part of the island’s history at least, there would have been a number of families to share the workload. Hard, yes, but also empowering, wholesome and true. Providing friends did not become enemies, as in the Banshees of Inisherin, the Shiants may once have been an island paradise.

With the present world appearing more removed from nature, from sanity and from truth by the day, I can’t help but see past community life, upon these awe-inspiring islands, through rose tinted spectacles. But I’m not complaining; I wouldn’t trade my sea gypsy life for anything.

To see more from Guy you can follow Sailing Free Spirit on Facebook, YouTube and Instagram.

Enjoyed reading this?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

-

-

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

-

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.