A collision and a fouled prop put Amanda and Victor Tettmar in a tricky situation mid-Channel, surrounded by shipping with night falling

Following an already eventful summer cruise to Brittany, our return Channel crossing suddenly became a lot more challenging.

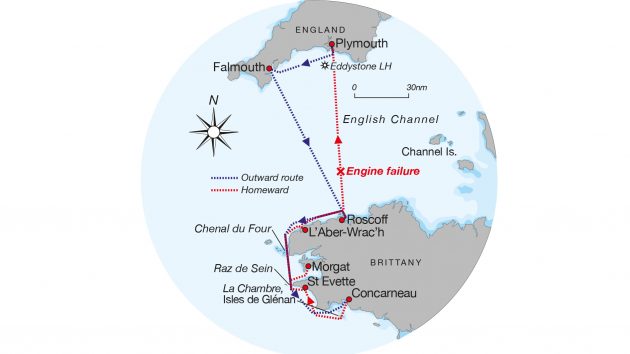

We’ve been sailing our 34ft yacht, Hummingbird for 8 years. We generally only sail as a couple and limit ourselves to day passages, with the Channel crossing being one of the longest we’ve undertaken. We started our cruise heading west from Plymouth to Falmouth, and then we crossed the Channel to Roscoff, in order to clear customs at a French Port of Entry.

We then headed west along the Brittany coast round Finisterre, passing through the Chenal du Four and Raz de Sein, with our southernmost point being Concarneau. From there we headed a few miles offshore to the Isles de Glénan, which we had been assured were an idyllic, almost Caribbean, archipelago.

Victor at the helm of Hummingbird. In calm conditions, they were only making 2-3 knots at times. Photo: Amanda Tettmar

First problem

We arrived in the Isles de Glénan, to blue skies, sunshine and clear blue waters. We picked up a mooring buoy and settled down for a relaxing day of swimming, paddle boarding and reading.

Our peace was rudely interrupted when an out-of-control 40ft motor cruiser reversed at speed into our stern, hitting our Hydrovane shaft with his bathing platform. They went on to bounce off another yacht, and only just managed to drop anchor and stop, within inches of hitting a third, before finally silencing their engine.

We initially thought we’d escaped unscathed, but closer inspection revealed a 30cm horizontal full-thickness crack about 10cm above the waterline. This continued to ooze water, despite us applying a plastic padding temporary repair to the inside. We decided to cut short our cruise and planned a direct route back to Plymouth via day hops and a few days later found ourselves back in Roscoff to check out of customs.

Having sailed for a few days we had established that there was no major ingress, but the oozing was worse on a port tack, when the starboard quarter submerged or in rougher seas, so we planned to motor back across the Channel on a very calm day.

The forecast was a Force 2-3 northeasterly wind, with a flat sea, but building over the next few days to Force 5 or 6 and moving into the north west. Because of the crack in the stern, we notified Falmouth Coastguard of our plans and were due to check in with them again, when we arrived safely in Plymouth.

Crossing the channel

We duly checked out of French customs (only a few hundred yards from Roscoff Marina) and set off at 1100 for an expected 18-hour, 90-mile crossing. As part of our upgrades, we had installed AIS, which we always rely on heavily to get through the busy shipping lanes.

Knowing the closest point of approach and when that will be, and seeing the vectors, helps us to weave between the huge ships moving through the English Channel. There are no traffic separation zones at this point, but the container vessels tend to stay within lanes along the southern Channel in this area.

Five hours and 25 miles away from Roscoff, the engine suddenly made a huge noise and the whole boat started vibrating violently. This was a new experience! We put the engine in neutral, reverse, and tried a variety of other ideas but always after a few seconds in gear the problem returned.

Only six Frances 34s were built. As pilothouse versions of the Victoria 34, they were powerful and comfortable cruising boats

We have secondary engine controls in the pilot house and also tried them, initially thinking it had solved the problem, but within a few minutes the noise and vibrating returned. By now it was cold, raining and gloomy. It was due to get dark at around 1900, and we were now approaching the shipping lanes.

Victor suggested going over the side to have a look at the propeller, but I felt this was too risky given that we were in the middle of the English Channel, it was imminently getting dark and was cold and drizzling!

With no engine power, we now had to decide whether to continue across the Channel under sail, or to sail back to Roscoff to get help. By now the wind had dropped to Force 1 to 2 still in the northeast, and it was almost dark.

The crack in the hull is just visible below the Hyrdrovane bracket, after being hit by a motor cruiser. Photo: Amanda Tettmar

Making a decision

In the end, no-one went in the sea to check the propeller. We were concerned about returning to the notoriously rocky and tidal, north Brittany coast with minimal control due to lack of wind and no engine, and in the dark. So, we set sails, and sailed where the wind would let us, in a generally northerly direction.

Sometimes we were barely moving as the wind died away completely at times during the night. We kept the engine happily running in neutral to power the instruments and especially to broadcast our position details on AIS.

The offending polypropylene rubble sack was eventually removed from the propeller. Photo: Amanda Tettmar

We kept a close watch on the radio and were prepared to call any shipping that was coming too close. We chose not to radio Falmouth coastguard as they were already aware of us because of the crack and we did have the sails as a means of propulsion.

We stuck to our normal two-hour watch system during the dark, drinking lots of cups of tea, and hot soup and having a hot meal to keep us feeling positive! At times we felt like a sitting duck with no manoeuvrability in the dark, surrounded by the lights of all these 400ft-plus freighters.

Dawn found us beyond the busiest shipping lanes, with the wind picking up, and a beautiful sunny day. The coastline of Devon was just appearing on the horizon. Dolphins came to play for half an hour. Our spirits lifted, the wind shifted slightly, we set our beautiful blue and green multipurpose genoa – a relic from Hummingbird’s past – and steered directly for Plymouth, but we were still only making 2-3 knots at times.

The coast of Devon finally appears under the bow, in sunny, calm conditions that belied the nerve-wracking night just spent at sea. Photo: Amanda Tettmar

Eventually, when we reached the Eddystone lighthouse, we picked up mobile phone signal and contacted our marina, who offered to tow us the final mile into our berth. However, we were still several hours away. When we made it into Plymouth Sound it was with great relief that we saw Speedy from the Mayflower Marina as we rounded Drakes Island.

Mike drew alongside with the words, ‘What’s that great white thing round your prop?’ He towed us into our berth, and then, with a deft flick of the boathook, retrieved the remains of a white polypropylene builder’s rubble bag from our prop.

It was nearly 32 hours since we’d left Roscoff but we’d made it in time for dinner. You expect to handle challenges at sea, but we were unlucky to have two tricky incidents to handle in one cruise!

Hummingbird is now on hard standing awaiting repairs, which will hopefully be done in time for next season.

Lessons learned

Diagnosing the problem – We now know what it sounds and feels like when the prop is seriously fouled. To be fair, we had thought the sensation to be a bit similar to that of seaweed fouling when we first run the engine at the beginning of the season. If we are unfortunate enough to have the same issue in future, we won’t need to spend hours figuring out the problem!

Going over the side – Should one of us have gone over the side mid-Channel? We still go round and round debating this. We were both safe and warm on board and were in no immediate danger whilst we were sailing, albeit very slowly. Maybe if we were younger, or there had been more people on board, we may have decided differently. If we had understood that the prop was definitely fouled, we could have chosen to investigate from the water once in sight of England and out of the shipping lanes, or in calm weather could have launched the dinghy, from which to wield a boat hook

Get a rope cutter – Our propeller is a three-blade Featherstream propeller in a skeg- hung rudder system. We had tried to fit a rope cutter in the past, but unfortunately, there is no room on our propeller shaft for one. In reality, we doubt any cutter could have got through the polypropylene bag.

AIS preparation – We could probably have programmed the AIS to broadcast that we had no engine manoeuvrability, and would consider doing so in future. To do this, we’d need to delve into the instruction manual as it’s not something most people do regularly.

Use negative incidents to build sailing resilience – We handled a much longer passage than usual and survived, so we now feel more confident in contemplating longer planned passages in future.

Enjoyed reading this?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

-

-

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

-

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.