After witnessing the wonders of the Gambier Islands’ flourishing reefs, two sailors go coral gardening with an inspiring group of conservationists

Floris is on the lookout at the bow, as we are sailing in uncharted waters. Some of the coral heads rise almost to the surface but, thanks to the high sun and clear water, Floris can easily see them. We keep them at a safe distance, and sail on until we find a patch of sandy bottom to anchor near the edge of the ring of coral reefs that encircle the Gambier archipelago in French Polynesia.

The water in the lagoon is flat, crystal clear and azure blue. Trees and bushes grow on several small islands. Puaumu, the picturesque island in front of us, is one of them.

‘This whole island is made of coral!’ Ivar observes when we go ashore. In the distance, large ocean rollers pound violently on the reef that rises steeply from the fathomless depths of the Pacific Ocean. Upon closer inspection of the beach we notice that some pieces of broken coral are quite large.

Bora Bora makes an amazing backdrop for a selfie for Floris (left) and Ivar. Photo: Floris van Hees and Ivar Smits

A vital ocean lifeforce

‘Fragments of the coral’s skeleton,’ Ivar analyses. The smallest pieces have become sand. Its snow-white colour is the reason why the water around the island looks bright blue. In combination with the island’s dark green palm leaves, it makes for a picture-perfect scene. In the coming weeks we will learn that coral is not only beautiful, but first and foremost of huge significance for marine life and coastal protection.

‘Our’ coral island is home to countless coconut palms. They have taken root and carry many coconuts despite the barren and salty coral soil. Over time, these pioneers have left a layer of fertile biomass on top of the coral, which has enabled other types of plants to grow.

The flora, in turn, attracts animal life, such as the bright red hermit crabs that feast on the contents of fallen coconuts. They carry spiral shells on their backs and can easily climb trees. In the treetops nest numerous terns, which we are careful not to disturb. Their droppings, or guano, also fertilises the island.

Floris and Ivar’s yacht Lucipara 2. Crushed fragments of white coral give the water a brilliant-blue hue. Photo: Floris van Hees and Ivar Smits

Underwater, the coral is alive, literally. We find it in all kinds of colours and shapes, from bonsai to bulb, from cauliflower to tree branch. The seabed close to shore is covered in it. The coral is a marine animal that protects itself with a skeleton of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). To make the skeleton, it removes carbon from the atmosphere in the form of CO2. While corals are slow to grow, over millions of years they have formed gigantic reefs. Rock-hard and razor-sharp, they are the fear of many sailors.

Equipped with snorkels we explore the underwater world. Fish of all colours and sizes, including reef sharks, swim around large blocks of coral. We are impressed by the enormous biodiversity that has developed on and around the coral. Yet when we want to take a closer look, the smaller fish quickly hide between openings in the coral and observe us from their shelter.

Article continues below…

It really illustrates how important the coral reefs are for these fish, both as a nursery and as a shelter. We are therefore not surprised to learn that coral reefs occupy less than 1% of the ocean floor, but are home to more than 25% of marine life.

Still with our heads submerged, we hear a soft, grinding sound. It comes from blue-green parrotfish that gnaw on the coral reef. With sturdy beaks resembling those of parrots, they have a special role in the maintenance of the reef. They eat algae, which mainly grow on dead coral, thereby limiting algae growth and removing dead coral.

Their appetite keeps the reefs in good condition. Over the course of a year, they defecate many kilos of fine, white coral sand. Washed up on shore, coconut palms and other plants make good use of the sand to take root, and underwater it provides a habitat for many types of crabs and shrimps. Parrotfish are therefore real team players, with an important role to maintain the health of the entire ecosystem.

Healthy coral is a nursery for many fish species and has a protective skeleton of calcium carbonate. Photo: Floris van Hees and Ivar Smits

A dangerous archipelago

Soon after leaving Gambier we enter an area in the Pacific known as the Tuamotus, which means ‘many islands’ in Polynesian. It is also referred to as the ‘Dangerous Archipelago’. The islands here are historically notorious among seafarers, because there are so many of them and they’re hardly elevated above sea level. It makes them difficult to spot from a distance. Waves violently break on their shores as if to warn: stay away! To avoid ship-wrecking on the coral, seafarers used to give the Tuamotus a wide berth.

‘The Polynesian and European explorers would have killed to get their hands on our digital sea charts,’ Ivar jokes. ‘They allow us to navigate these atolls safely and easily find narrow gaps in the coral ring known as “passes”. This way we can enter the atolls and explore a few of them from the relative calm of their lagoons.’

The Tahanea atoll comes highly recommended. Our pilot books and sailors who went before us cite it as a highlight of the Tuamotus. It has multiple navigable passes, is uninhabited, and its underwater biodiversity is unparalleled. How right they are.

We watch our anchor set on the sandy bottom and instantly spot as many as nine curious sharks. Colourful triggerfish flock to our boat to nibble

at the seaweed on our hull. The palm tree-lined white beaches right in front of us make for picture-perfect postcard views.

The coral garden in Mo’orea. Photo: Ryan Borne; Ben Thouward / Coral Gardeners

The impact of tourism

The next day we hitch a dinghy ride to reach one of the smaller passes. Fresh ocean water flows into the lagoon here, which means there is a lot of food, and thus many fish gather here. Although the waves are considerable and the current quite strong, we feel safe in the pass with the dinghy floating close by. ‘Look, down there!’ Floris shouts enthusiastically, being the first to have jumped in.

Majestic manta rays are feeding on plankton like big vacuum cleaners. With their wingspan of close to three metres, they effortlessly float through the water below us, as if in flight. It makes the black-tip reef sharks next to them look tiny.

Anchored at Tahanea. Photo: Floris van Hees and Ivar Smits

We soon get used to seeing healthy coral and a beautiful, diverse underwater world. In Gambier and the Tuamotus we regularly imagined ourselves in a sea aquarium. We are therefore quite shocked when, a few weeks later, we snorkel at our anchorage in Mo’orea, a fairly touristy island near Tahiti.

The coral is in bad shape; it is brown and overgrown with aquatic plants. Unfortunately, we read that the coral quality here corresponds to a broader trend. About half of the coral worldwide has died since the 1950s. Warmer and more acidic seawater as a result of climate breakdown is to blame, in combination with overfishing and pollution.

That’s tragic because coral reefs are incredibly important, not only for the biodiversity in the oceans, but also for people. Millions of people depend directly and indirectly on fishing for their livelihoods and food. Tourists flock to tropical beaches to dive in the beautiful underwater world. Coral reefs also protect the coast from storms. The annual total contribution of coral reefs to the economy is estimated to be over 30 billion US dollars.

Floris (left) and Ivar snorkelling in Gambier. Photo: Floris van Hees and Ivar Smits

Fortunately, there are people in Mo’orea who give ailing coral reefs a helping hand. We meet Taiano Teiho of the NGO called Coral Gardeners. He explains what drives him and his colleagues and what they try to achieve. ‘We are a group of 15 young islanders who love the ocean.

A few years ago, we decided to do something about the decline of the coral reefs on our island. To tackle the root causes, we run campaigns to raise awareness about the threats to coral reefs, such as in schools and via our social media channels. We also implement a concrete, practical solution locally: the transplanting of coral.’

How does that work, we ask Taiano curiously. ‘We collect pieces of healthy coral and bring them to a designated area: our coral garden. There we let the coral pieces grow until they are big enough. Then we transplant them to reefs that are in bad shape. It’s a lot of effort, but it works! In three years, we have already performed more than 14,000 transplants that have made the reefs visibly healthier.’

Conservation work is helping to re-grow precious coral. Photo: Floris van Hees and Ivar Smits

The next day we take a closer look at their nursery. A few metres below the surface, on a shoal within Mo’orea’s lagoon, the Coral Gardeners have installed large stations on which they re-grow hundreds of small pieces of coral. It’s a delightful sight amid the barren seabed. You can support their work by adopting a piece of coral via their website – we intend to do the same! Visit https://coralgardeners.org to find out more about their work.

Ecosystem restoration is possible

We get a lot of positive energy from the young islanders of Coral Gardeners. With beautiful images and a smart social media strategy, they have gathered many thousands of followers and received sizeable contributions. In this way, they not only increase awareness about the importance of coral and what’s threatening it, but they also work on an actual solution to help these vital yet vulnerable ecosystems recover.

In Gambier we witnessed that it is not too late for the coral reefs. Everyone can play a role in combating climate breakdown, reducing pollution and – via the Coral Gardeners – increasing biodiversity by restoring coral reefs. What role do you choose to play?

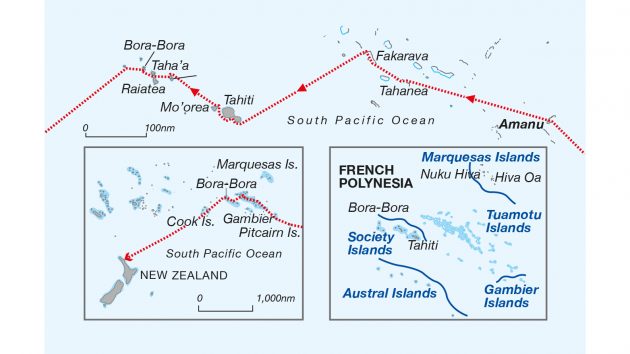

Cruising in French Polynesia

Five archipelagos make up French Polynesia: the Marquesas, Tuamotus, Gambier, Austral Islands, and Society Islands. Spread out over an area as large as the EU, they provide fantastic cruising opportunities.

The country is part of France but has extensive independence, such as its own currency. On most islands, there are few facilities for sailors, aside from the Society Islands, which are the main charter hub.

A peculiarity about this area are the rings of coral that surround entire archipelagos (Gambier) or individual islands (Society Islands). In some archipelagos they are absent (Austral Island, Marquesas) or all that is left of sunken volcanic islands, resulting in atolls (Tuamotus). While some rings of coral are impassable, others have a few openings through which boats can carefully enter.

Fenders serve as floats to lift the anchor chain and protect coral heads. Photo: Floris van Hees and Ivar Smits

Anchors and Coral don’t mix

The clear water encountered in many places is convenient for anchoring. You can see your anchor on the bottom in water depths of up to 15m, but be wary of coral heads! Light blue water suggests the bottom is sandy and good for anchoring. Still, it is often difficult to find a large enough spot to turn a complete circle around your anchor. When the wind direction changes, your chain can get stuck behind a coral head and damage it. The solution is to attach fenders to the chain after you have set the anchor, keeping the chain clear of the bottom.

Anchoring Limitations

Pearl farms have made anchoring in some bays impossible and can be hazardous within lagoons. On Tahiti, anchoring is only allowed in a few places. In Mo’orea clearly defined zones allow for short (48 hours) or longer (6-day) stays. Anchoring in Bora-Bora is near impossible. For up-to-date information, visit http://voiliers.asso.pf.

Cruising Guides

Noonsite and apps like Navily and NoForeignLand provide helpful details on anchorages and amenities on land. Various cruisers have contributed to ‘compendiums’ for the different archipelagos. They can be downloaded from https://svsoggypaws.com/files/#pacific.

Enjoyed reading this?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

-

-

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

-

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.