In this abridged story from his book The £200 Millionaire, Weston Martyr describes the meeting of a sailing bank clerk and a drug smuggler in Smith Versus Lichtensteiger

Smith stood five foot five in his boots, weighed nearly 10 stone in his winter clothes and an overcoat, and he had a flat chest and a round stomach. Smith was a clerk in a small branch bank in East Anglia; he was not an athlete but he had fought for a year in France without ever seeing his enemy when a piece of shrapnel reduced his fighting efficiency by abolishing the biceps of one arm.

For 49 weeks he laboured faithfully at his desk. But every year in April Smith suddenly came to life. For he was a yachtsman and he owned a tiny yacht which he called Kate and loved with a great love. The spring evenings he spent fitting out, painting and fussing over his boat. Thereafter, as early as possible every Saturday afternoon, he set sail and cruised alone returning again as late as possible on Sunday night. And every summer when his holidays came round he would sail away from East Anglia to voyage afar.

The year Smith encountered Lichtensteiger he had sailed as far east as Flushing and was on his way back when a spell of bad weather drove him into Ostend. Lichtensteiger was also detained at Ostend; but not by the weather. He had come from Alexandria with a rubber tube stuffed full of morphine wound round his waist. A Customs official at Dover (who had suspicions but no proof) had debarred him as an ‘undesirable alien’ from entering the United Kingdom.

Lichtensteiger was a Swiss who stood 6ft 1in in his socks, weighed 14 stone stripped and he had a round chest and a flat stomach. He was as strong as a gorilla and had never done an honest day’s work in his life.

Smith was due back at his bank again in three days but could not hope to sail single-handed against strong headwinds. Lichtensteiger, having spotted ‘an Englishman, a fool’, soon entered into conversation with Smith who admitted he was running late for a return to Harwich and would welcome help from an extra hand.

“It’s illegal. I’m sorry, but I can’t risk it. If I got caught they might put us in prison!”

At sea, Lichtensteiger said he wanted to be landed on a lonely stretch of beach, thereby avoiding Customs clearance.

Smith answered: ‘It’s illegal. I might get into trouble over it, and I can’t afford to get into trouble. If they heard in the bank I’d lose my job. I’d be ruined. I’m sorry, but I can’t risk it. Why, if I got caught they might put us in prison!’

But Smith did not get any further. Lichtensteiger interrupted him. He drove his heel with all his might into Smith’s stomach and Smith doubled up with a grunt and dropped on the cockpit floor. Lichtensteiger then kicked him in the back and the mouth, spat in his face and stamped on him.

Smith vomited. When he could speak he said, ‘Don’t kick me again. I’ll do it. I’ll do what you want.’

And approaching the coast at night, Lichtensteiger said: ‘What’s that light in front there?’

‘Lighthouse,’ said Smith. ‘That’s the South Foreland light. I’m steering for it. The lights of Deal will show up to the right of it presently and then we’ll pick out a dark patch of coast and I’ll steer in for it.’

Sounding over the side with the lead-line, he ran Kate into the wind, lowered the jib and let go his anchor with a rattle and a splash.

‘Cut out that flaming racket,’ hissed Lichtensteiger. ‘Trying to give the show away are you, or what? You watch your step, damn you.’

‘You watch yours,’ said Smith, drawing the dinghy alongside. ‘Get in carefully or you’ll upset.’

‘You get in first,’ replied Lichtensteiger. ‘Take hold of my two bags and then I’ll get in after. And you want to take pains we don’t upset. If we do, there’ll be a nasty accident – to your neck! I guess I can wring it for you as quick under water as I can here. You watch out now and go slow. You haven’t done with me yet, don’t you kid yourself.’

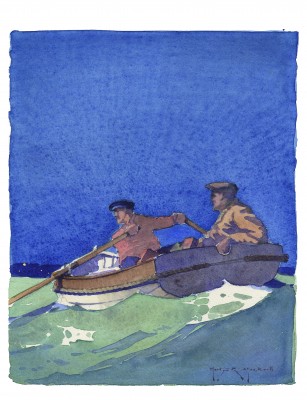

Smith rowed the dinghy towards the shore. Presently the boat grounded on the sand and Lichtensteiger jumped out. He looked around him for a while and listened intently; but except for the sound of the little waves breaking and the distant lights of the town, there was nothing to be heard or seen.

‘All right,’ said Lichtensteiger. Smith said nothing. He pushed off from the beach and rowed away silently into the darkness. Lichtensteiger laughed. He turned and walked inland with a suitcase in each hand. He felt the sand under his feet give way to shingle, the shingle to turf and the turf to a hard road surface. Lichtensteiger laughed again. It amused him to think that getting himself unnoticed into England should prove, after all, to be so ridiculously easy.

He turned to the left and walked rapidly for half a mile before he came to a fork in the road and a signpost. It was too dark for him to see; but he stacked his suitcases against the post and climbing on them struck a match. He read: ‘Calais – 11⁄2’.

– Exert from the book, The £200 Millionaire by Weston Martyr