Chris Beeson picks 50 innovations that have changed our safety, navigation, life on deck and more

50 innovations that changed sailing

SAFETY

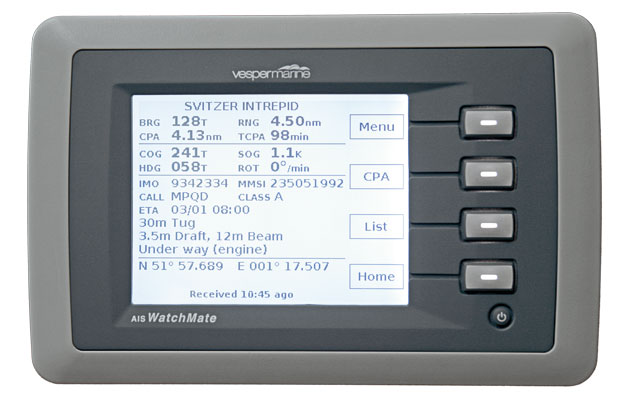

1. AIS

This is the biggest step in marine safety since President Clinton made GPS publicly available in 1996. An AIS receiver allows you to monitor shipping traffic over 300 tonnes, and a transceiver also broadcasts your position to other AIS-enabled traffic. They come as stand-alone screens, chartplotter overlays and in fixed VHF units. If you have a DSC VHF radio, you can contact a target using its MMSI number, ensuring they know about you. There are personal AIS beacons too, that activate if you fall overboard and trigger an MOB alert on the plotter of your boat and any AIS-enabled plotter in range. However, most sailors don’t use the transceiver’s silent button, which stops broadcasting your data, so screens can become cluttered.

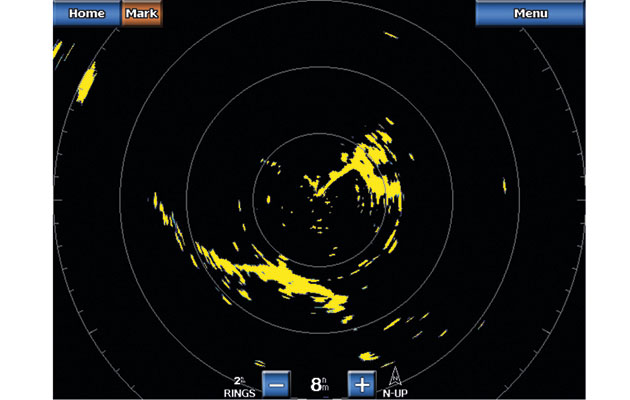

2. Radar

Radar has helped mariners avoid countless collisions and can also detect the weather and squalls. Its wartime technology fires out beams of X- and S-band microwaves and detects signals returned from unseen targets. Recently Navico unveiled Broadband radar technology, adapted from a system used by aircraft to detect their height when coming in to land. It needs no warm-up time, uses less power and there’s no ‘main bang’ of microwaves next to the receiver so you can detect objects well within 10 metres (30 feet), which is impressive, but it would need to be a seriously foggy day to be useful at that range.

3. Automatic lifejacket

The self-inflating lifejacket, even one with up to 275N of flotation, packs up small enough to wear without restriction. It’s durable, can be re-used by replacing the inflation canister, and will save your life if you fall overboard unconscious. Make sure you have a light, crotch straps and a sprayhood though.

4. RTE

A Radar Target Enhancer detects a radar ping and amplifies the return signal, ensuring you return a big, bright, unmissable echo. Both the main RTE manufacturers, SeaMe and EchoMax, now produce models that ensure returns in X- and S-band radar frequencies, the two used by shipping.

5. Tether

‘One hand for the ship’ is a great theory, but if you’ve been on deck in a storm for four hours, you’ll be exhausted. If a wave sweeps the deck, you could be swept over the side before you can grab anything. A good safety harness, with three self-locking, stainless steel hooks and one-handed operation, will keep you onboard. Inspect the stitching regularly.

6. Automatic liferaft

When heavy weather, sinking, capsize or fire aboard threaten to turn your yacht into a death trap, it’s reassuring to know that a transom-mounted automatic liferaft, with a hydrostatic release, buys you the time to try and save the ship without having to worry about hauling the liferaft out of its cockpit locker and tying on the painter.

7. Sea anchor

This is a device that can save your life. You’re in storm conditions and, despite your best efforts to claw offshore, making serious leeway. You’re 15 miles from a lee shore but it’s too deep to anchor. Rig the sea anchor and your boat will ride out the storm with the very minimum of drift. Even in mid-ocean, you can deploy the sea anchor, set your AIS alarm and can slip down below for a few hours’ respite. It can ‘stop’ the storm for you. Be sure to rig the trip line properly.

8. VHF radio

Marine VHF radio was invented by Marconi in 1896. Before this, a ship in distress was on its own unless it was within sight of land or another ship. Marconi understood the many advantages of ship-to-shore communications – indeed the British and American companies he founded refused to communicate with non-Marconi ships – but it was the Titanic tragedy in 1912 that made VHF essential on large ships.

9. GMDSS

Using satellite and terrestrial communications, the Global Maritime Distress and Safety System (GMDSS) has transformed safety. Sailors get forecasts by NavTex, hail traffic and raise alarm using DSC VHF, or trigger an EPIRB or PLB to alert rescue services via their GPS satellite position.

10. Gas alarm

If LPG leaks, your boat could explode. If Carbon Monoxide leaks, from your engine exhaust or a generator, you could be asphyxiated. If a fire starts while you’re asleep, you could die of smoke inhalation without waking. You can avoid all three of these lethal scenarios by fitting, maintaining and testing alarms.

NAVIGATION

11. GPS system

Navigation used to be a near-mystical practice, using currents, seasonal winds and wave patterns. The Minoans of Crete navigated by stars. Celestial navigation is mentioned in Homer’s Odyssey. It was the 18th century before ships’ clocks became accurate enough to measure longitude. Using a sextant and calculating latitude with reduction tables is not a simple skill to learn – assuming the planet or star you’re shooting is visible. Since the Second World War, when Decca and Loran were pioneered, accurate position fixing became easier but still unreliable. Both were effectively made redundant by the US military’s constellation of GPS (Global Positioning System) satellites. The project began with 24 satellites in 1973 and became operational in 1994, enabling anyone to read their latitude and longitude with an accuracy that would have made earlier navigators gasp.

12. Charts

Accurate marine cartography emerged in the 18th century, most notably via Capt James Cook. Where once there were fanciful outlines of continents and ‘Here be serpents’ warnings, Cook and his peers brought accurate surveys and soundings. Indeed many of the charts he drew of areas around New Zealand and Australia could still be used today.

13. Chartplotter

The chartplotter was another leap in popularising sail cruising. It uses GPS to place a continually updated position on an electronic chart, enabling the yachtsman to avoid charted hazards. Now you can create routes, pre-plan your voyage, and even overlay radar, weather and AIS data. Just don’t forget to use your eyes too.

14. Almanac

The first almanac, published in the UK in 1767, gave navigators the positions of the major celestial bodies at any given time, enabling them to fix their position. The nautical almanac we know and love, which gives us tidal and port data, was first compiled by Capt O M Watts and published by Harold Brunton-Reed (hence Reed’s Nautical almanac) in 1932.

15. Hand-bearing compass

Often seen perched in the palm of pilotage enthusiasts, the hand-bearing compass gives you accurate bearings on sea and land marks, enabling you to establish your relative position and safely negotiate your way without having to crouch next to the ship’s compass.

16. Binoculars

‘Bins’ have been around almost as long as the telescope and always offered the advantage of 3D vision. However, in the 17th century optics weren’t good enough to present identical images to both eyes. Also, using the standard Galilean series of lenses, they would need to be the same length as a telescope to match their magnification. It was in 1854, when Ignazio Porro invented his eponymous prisms, that the bins we know today took shape.

17. Pilot book

As the name suggests, pilot books contained the local knowledge pilots needed to guide vessels safely through narrows, channels and rocks. The authors of early pilot books, written for big ships, had no particular interest in sharing their research with leisure yachtsmen, so it was left to obsessive creek-crawling yachtsmen to provide in-depth information about stretches of coast in books like Frank Cowper’s Sailing Tours published in 1892, and K Adlard Coles’ 1939 publication, Sailing on the South Coast.

18. PC navigation

There is an ever-increasing number of pros to PC navigation as more and more companies release PC-based software and hardware. Using a laptop ‘future-proofs’ your navigation set-up because it can be updated so easily, they’re much cheaper and you can store pictures, watch films, play music, get forecasts and send email too. The only downside of a cheap laptop is durability in the corrosive, damp sea air, so go for a marinised one with a solid state hard drive.

19. Navionics app

Any yachtsman with an iPhone or iPad is almost certain to have the Navionics chart app installed, turning the humble smartphone into a small chartplotter. It’s very useful for planning and recording voyages but don’t be tempted to rely on it. As well as the short battery life and vulnerability to water, the iPhone’s GPS is assisted, ie it triangulates your position using mobile signals. Without that, or a GPS plug-in, it can take a while to locate you.

20. Tablets

Hand-in-hand with the Navionics app is the iPad. And once you’ve finished navigating you can read books, newspapers, magazines like Yachting Monthly, watch movies, listen to music wherever you are. Plenty of companies are now releasing cases that protect your snazzy tablet while still enabling it to be used, and mounting systems that allow them to be used on deck.

DECKGEAR

21. Self-steering

Most of us sail shorthanded so the idea that you can leave the helm to trim a sail, grab a jacket, mix a G&T, nip to the heads or just enjoy the day, is truly a blessing. Like many marine innovations, it has developed from yacht racing, in this case the peculiarly British sport of solo yacht racing. In the run-up to the inaugural OSTAR transatlantic race in 1960, Cockleshell Hero Lt Cdr Herbert George ‘Blondie’ Hasler pioneered a device that, via a system of pulleys and servos, enabled his Folkboat, Jester, to sail a wind angle without constant helming, making him the father of self-steering. Now we have tiller pilots and integrated autopilots too.

22. Winches

Technically speaking your yacht (unless it’s a superyacht) hasn’t got as many winches as you think. They’re all capstans. Winches store cable on the drum (like your furling gear), capstans don’t. However, for an easy life, let’s accept the misnomer and press on. Before the advent of the winch, yachts needed much larger crews, who relied on a block-and-tackle to haul gaff spars aloft, or sheet in ballooning headsails. Sailplans were different: the gaff and cutter rig evolved to split up the canvas into smaller sails that were more easily handled. After the winch came the more efficient Bermudian sloop rig, with two much bigger sails. When the self- tailing winch was invented, a crewman could concentrate on grinding without another crewmember ‘tailing’. Then came electric winches – still frowned upon in some circles but undeniably empowering for shorthanded crews on big yachts, trim-in/ease-out winches and recently four-speed winches from Pontos.

23. Electric windlass

Weighing anchor manually can keep you keep fit, but I’ve also seen people suffer back injuries, mangled hands and get covered in evil-smelling mud. Sometimes, they just give up the ghost and drop the lot in a huff. With an electric windlass, you can drop and weigh anchor at the push of a button – even from the wheel – and this makes us more likely to anchor, which is a singular pleasure.

24. Dyneema

Stretchy cordage has its place – anchor rode for instance – but it’s a menace when it comes to running rigging. That’s where Dyneema is such a boon. It’s a tradename for cordage made from ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene. It’s so light that it floats, it has a yield strength nearly five times that of steel and it barely stretches at all, so your halyards stay as tight as you want them to be.

25. Spade anchor

In the mid 1990s France’s Alain Poiraud tired of having his new anchor design turned down by manufacturers so he set up a factory in Tunisia and made it himself. The Spade’s sharp triangular fluke is concave for better holding power and it has a buoyancy chamber in the crown, which loads half the anchor’s weight onto the tip. Add to that end plates to stop it digging in on its edge, and you have a game-changer.

26. Sprayhood

At some stage, a yachtsman said, ‘I love sailing, but does it have to be so wet and windy?’ The sprayhood transforms the cockpit into something of a sanctuary, sheltered from the elements. There’s evidence of similar devices being placed over hatches on Nelson’s ships, where they were known as ‘collapsible scuttles’. Paul Lees from Crusader Sails remembers sewing one in the 1960s but it was in the 1970s that they really caught on – around the time sail cruising started to become really popular. Coincidence?

27. Roller reefing

The splendidly-named Maj Robert Fiennes Wykeham-Martin is believed to have invented the first sail furler in the 1890s. The model he invented, fashioned from bronze, is still available and outwardly it’s remarkably similar to those on sale today. The materials may have changed and there have been a few refinements but the good Major’s invention is clearly difficult to improve.

28. Clutches

Exactly when the pinrail morphed into the cleat is unclear but, while both are undeniably effective, it takes a while to secure ropes to either and releasing the load can be an all-or-nothing affair. Camcleats, which have been around since the late 19th century, secured lines in an instant but had limited loads. Later came levered cam wheels, known as spin locks, but the modern clutch, used with a winch, offers the best possible combination of load bearing and ease of release.

29. Super siphon pump

Anyone who knows more than they would care to about the taste of diesel will recognise this item as a saviour in siphon form. One end of the hose has a ball bearing and a spring. Lower that end into the diesel and jiggle it vertically. On the downstroke, the ball bearing opens the valve, filling it with diesel, then closes on the upstroke. After a few jiggles the siphon effect takes over. Genius.

30. Inflatable tender

The first small inflatable craft were inflated animal skins and there are records of their use in Assyria as far back as 880BC. Wellington tested inflatable bridges in 1839 and in 1845 Lt Peter Halkett designed rubberised canvas boats for use in Arctic exploration. They were used by downed pilots throughout WWII but the first iconic inflatable tenders were the Avon Redcrest and Redstart in 1959.

SYSTEMS

31. Automatic bilge pump

In the days before electricity onboard, when boats were wooden, you needed to swab out the bilge after every sail. If you sprung a particularly serious leak, the first you used to know about it was a leeward locker brimful of briney. Once batteries appeared onboard, it became possible to power pumps. Add to that a float switch to turn it on and off and you have a tireless, ever-vigilant, low maintenance, undemanding and obedient crew member patrolling the bilge.

32. Fresh water system

I like a pint, I’d never deny it. I don’t want six with every meal though. I daresay Nelson’s crew didn’t either but, as there was no fresh water onboard – or indeed anywhere except rivers and lakes – beer it had to be. A pressurised fresh water system means cups of tea, taps that work, showers even. It’s hugely civilising and a big step towards the home-from-home that modern cruisers desire.

33. Plastic through-hull

Surely no one now needs reminding of the appalling inadequacy of some seacocks, the ridiculousness of commissioning new boats in which the RCD stipulates they need no more than a five-year lifespan, and the difficulty of identifying exactly what type of alloy your seacocks are made from. Plastic seacocks like the Marelon or TruDesign ranges are corrosion-free and fire-resistant, which makes them pretty much perfect for underwater through-hulls.

34. Folding/feathering prop

If you’re sailing at 5 knots with a three-blade fixed prop locked off, you should be doing 6 knots. On a 30-mile voyage, that adds an hour to your passage time. There’s evidence to suggest that freewheeling will half that loss but it’s still significant. Folding and feathering props massively reduce the drag by slipstreaming. They’re not cheap and their performance isn’t always reliable, particularly steaming into steep seas, but in most sailing conditions you would be gliding along much quicker.

35. Diesel engine

The diesel engine is safer, more economical, longer lasting and produces no electromagnetic interference

By 1898 Rudolf Diesel’s engine technology was in use onboard marine craft and we’ve never looked back. Its advantages over other forms of propulsion, petrol say, are many. First, diesel can be burned using a wick system but it won’t explode. Nor does a diesel engine need spark plugs or coils, which can create electromagnetic interference. Once running it needs no electricity. Diesels last longer too, and emit less heat and carbon monoxide. As battery technology and price needs to evolve a while longer before electric propulsion becomes viable on a large scale, the diesel looks set to stay.

36. Stove

After a chilly day at the helm, few things warm the cockles like a cup of tea or a hot meal. That’s why stoves have always been popular on boats. I’ve experienced a few flare-ups with paraffin-burning Primus stoves – operator error I’m sure, but I’m no Red Adair so I’m not a big fan. A professionally-installed, well-maintained and safely used gas system brings the convenience of the kitchen to the galley. If you sail a pocket cruiser, save some space and go for a meths burner.

37. Antifoul

Antifoul was pioneered by copper-bottomed Royal Navy ingenuity, giving us the edge in speed and manoeuvrability at Trafalgar and elsewhere. Since then we’ve slapped on toxic potions involving lime, arsenic, mercury, DDT and, until recently, TBT to keep our hulls smooth, all thankfully now banned. Now we’re back to copper – though maybe not for much longer. Antifouling is a perennial bugbear. First, there’s the dilemma of which works best, then there’s the season-opening rite of refreshing it, an annual ritual of penance. However, without it, we would spend several weekends a season drying out and chiselling off all manner of fearsome-looking beasties, or dragging the hanging gardens of Babylon under our hulls.

38. Electrical systems

There are few pleasures that can’t be improved by the warm flickering glow of a hurricane lamp but there’s an awful lot of sooty pfaffing around involved in filling and lighting them. Flicking a switch is far more convenient. You can start your engine without giving yourself a hernia, run your electronics, recharge your phone and camera, which makes a compelling argument for onboard electrics.

39. Lithium batteries

There’s nothing wrong with lead-acid batteries – until you look at the alternative. Lithium Ion batteries, like the ones in your mobile phone or camera, have about 3.5 times the power density of lead acid batteries, so you can store the same capacity and save two-thirds of the weight. You can also discharge them to around 10 per cent capacity, whereas you’re advised not to go below 50 per cent charge with lead-acid. They charge four times as fast, hold charge better and last nearly three times longer. The downside? Overcharging can be hazardous, so get a smart battery with built-in defences, and the price.

40. Push-button berthing

Squeezing into a tight berth is a nerve-wracking event. One slight miscalculation and you could cause thousands of pounds of physical damage, as well as shattering the trust and faith, carefully nurtured over the years, that your puppy-eyed crew has in you. In seconds your pulpit and your reputation could be bent beyond recognition. Add to this an audience of drooling rubberneckers, willing you to fail, and you have temple-pummeling stress. The Dock n Go system, pioneered by Jeanneau engineers, features a rotating saildrive that works in tandem with a bow thruster, both controlled from the helm using a joystick. You can crab sideways into the tightest berth alongside, spin the boat on her keel to back her down onto a finger pontoon and anything in between. Precision control. Others have followed the lead but all have had issues so it’s fair to say we’re not there yet (bow and stern thrusters aside). If we can crack it, mooring will lose its terror and become Zen-like and error-free (and marina bars will lose the free cabaret).

HISTORICAL

41. Sextant

These days noonsite is better known as a website but it was the day’s biggest event for sailors of yesteryear

The stars have been used for navigation since 2000BC. Polaris’ constant position above the North Pole was known by Arabian sailors who used the fingers of an outstretched arm to judge its altitude. Around 1,000 years ago navigation cemented its relationship with the stars with the quadrant, which measured altitude using a plumb line, and the astrolabe. Both instruments remained popular and evolved but it was the advent of accurate optics, enabling the use of prisms, that brought the night sky into the navigator’s realm. In 1731, London’s John Hadley and Philadelphia’s Thomas Godfrey simultaneously invented the octant, and by 1759, an auspicious year for navigation, John Bird had refined it to produce the first sextant. Less than 10 years later, Her Majesty’s Nautical Almanac Office published the first almanac with all the celestial information required to calculate latitude accurately.

42. Echosounder

We’ve always had the leadline, armed with tallow to pick up traces of the seabed, but it’s not much use in waters deeper than 25 fathoms (150ft/46m) and it’s unreliable underway. The echosounder was pioneered by Britain’s Lewis Richardson, who filed the first patent in 1912, a month after the Titanic sank, and it was used in anti-submarine action in the First World War. The first ad we can find in Yachting Monthly is the Fairway in January 1959. Now we even have forward-looking sonar.

43. Polyester sails

Sails used to be made of linen, cotton or hemp derivatives. These kept shape poorly and needed regular recutting. They absorbed water, became very heavy, and UV left them rotten in fairly short order. Thank heavens, then, for polyethylene terephthalate, aka polyester, or DuPont’s Dacron, which first appeared in sailmakers’ lofts in the early 1950s. Once UV-resistant resins had been perfected, the cloth was ready to make a cruiser’s life much easier.

44. Chronometer

Ruling the waves was tricky for Britannia in the 18th Century. Clocks were inaccurate at sea, and so were the resulting longitude calculations. Parliament posted a prize of £20,000 (over £2m today) for a clock that would solve the problem. Yorkshire clock maker John Harrison finally cracked it in 1759 with his legendary H4 chronometer. The government never gave him the entire prize but Harrison died a rich man, aged 83. Capt James Cook used a copy of the H4, which cost 30 per cent of the ship’s build cost, on his second and third voyages in the South Pacific and praised the accuracy of the watch.

45. Stainless steel rigging

Stainless steel rigging was introduced in the late 1950s and, though we take it for granted or even grumble about rust at the terminals, it was a huge step forward. Before that, rigging was galvanised steel and every season it needed to be coated with a mixture of linseed oil and varnish to protect it from corrosion. In the 19th century standing rigging was generally hemp rope, which needed regular applications of a glutinous mixture of pine, or Stockholm, tar and varnish to prevent it from becoming rotten. And you thought antifouling was a pain…

46. Aluminium mast

For centuries boatbuilders have hacked down straight, true trees and used them as masts. However, the strongest mast is a single tree so height was limited, they were heavy, with large cross sections and they rot. Unsurprisingly it was the racing fraternity that found a better idea, Harold Stirling Vanderbilt in this case, whose J-Class yacht Enterprise won the America’s Cup in 1930 with the first aluminium mast, which was a full ton lighter than the wooden spar on Sir Thomas Lipton’s Shamrock V. Needless to say, Enterprise romped home in every race, and the nascent cruising fraternity had an endless supply of masts.

47. Gore-Tex

We all appreciate the advances in technical clothing – most have come within living memory. For Cape Horners, foul weather gear meant leather boots and a linseed oil-soaked canvas coat. Since then we’ve been through rubberised garments that helped you sweat prodigiously, leaky cuffs and necks, to the point where clothing can genuinely keep you dry and comfortable. To quote Butch Dalrymple-Smith, who sailed on Sayula II, the first Whitbread Race winner in 1973-74, ‘I’m very jealous of the foul weather gear they have today. All ours kept out was the fish.’

48. Barometer

In the mid-17th century, the Grand Duke of Tuscany was struggling to lift water 12m with a suction pump. The limit was 10m. In 1643, Italian mathematician Evangelista Torricelli wanted to know why so he filled a 1m-long glass tube with mercury, 14 times denser than water, and inverted it in a dish. The mercury dropped by 24cm, then held. He had created the first sustained vacuum, dubbed a Torricellian vacuum, and, unwittingly, the first barometer. It wasn’t much use to the Grand Duke but it enabled scientists to link variations in the level of mercury with weather. After 200 years of mercury accidents, it was Frenchman Lucien Vidie who invented the aneroid barometer in 1843, rendering the barometer cheaper and more portable.

49. Marina berths

The swinging mooring fraternity may view berth-holders as cosseted fops, but for convenience, the marina is unbeatable, and it has helped cruising’s rise in popularity. Britain’s first marina was the 265-berth Birdham Pool near Chichester, West Sussex, which was developed in the 1930s. The pool itself is an old tidal mill pool and the mill is still there, next to the lock. The world’s largest marina is reputed to be Marina del Rey in Los Angeles, just south of Venice Beach, with some 6,000 berths.

50. GRP

YM’s Dick Durham argues that marine plywood was a greater invention than GRP, because it gave birth to the DIY home-build, enabling people to build their own yacht with simple plans. It’s a fair assertion but I believe GRP was a bigger innovation. Invented, as so many things were, by the Brits, it was used during WWII – ironically, instead of moulded plywood – to make aircraft radomes. It was lighter and quicker to fabricate. In the 1950s it made its way into yacht hulls and 60 years later, it’s still there. It’s cheap, strong, relatively light, easy to repair and lends itself readily to mass production. However, its primary virtue, longevity, is also its biggest problem. How do you recycle a plastic boat?

For all the latest from the sailing world, follow our social media channels Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Have you thought about taking out a subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine?

Subscriptions are available in both print and digital editions through our official online shop Magazines Direct and all postage and delivery costs are included.

- Yachting Monthly is packed with all the information you need to help you get the most from your time on the water.

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our expert skippers and sailors

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment will ensure you buy the best whatever your budget

- If you are looking to cruise away with friends Yachting Monthly will give you plenty of ideas of where to sail and anchor