How would you deal with a fire in the galley or the engine room? What’s the best way to prevent fires onboard? Chris Beeson and the Crash Test Boat Team find out

Crash Test Boat – Fire

Fire is without doubt the most deadly disaster we’ve re-created in the Crash Test Boat series. A capsize or knockdown is dangerous, but its effects can be mitigated. Dismasting is a drama that doesn’t always turn into a crisis. A hole in the hull, though a serious threat that could sink the boat, is an incident that might be managed with bilge pumps or any of the methods we tested. But when fire takes hold, smoke can be deadly and if the flames are beyond control, crew can be injured and the boat may be lost if her crew have to abandon her.

In 2010, RNLI lifeboats were launched in response to 120 fire incidents on boats in the UK and a total of 109 people were rescued. In 2009, there were 97 launches. The good news for yachtsmen is that in both years, only 28 of these incidents involved sailing yachts. Most call-outs were to motorboats, some with petrol engines. The RNLI’s lifeboat crews, as a rule, focus on rescuing people and do not fight the fires themselves, although they are trained to deal with fire and have a simulator at Poole that puts them through their paces in a realistic (and hot) scenario.

Every fire has three elements in common: heat, fuel and oxygen. If one of those elements is missing, a fire won’t start. If one of those elements is removed, any fire can be extinguished

Heat can be produced by a stove in the galley, an engine, a heater, a lamp, a candle, a cigarette, faulty electrical equipment, a short circuit, trapped or folded wiring. At sea it’s generally windier than in port, so oxygen is abundant and we encourage its circulation. What about fuel? Let’s look at your boat. The hull is most likely GRP, which is glassfibre mat infused with flammable resin, the interior is probably wooden and the furnishings foam and fabric.

Every cruising yacht is, in effect, a floating brazier, stuffed with fuel and shot through with ventilation holes. If a fire takes hold, few things will burn as well. Indeed, the fact that there aren’t more catastrophic fires is testament to the general good practice yachtsmen exercise. The Boat Safety Scheme (www.boatsafetyscheme.com) states that, on average, there are 89 fire-related accidents each year on privately owned boats and three fatalities. Further research indicates that many of these are petrol fires on motorboats, but negligence can be fatal.

The aim of this test, then, is to save the boat and crew. First, we’ll look at firefighting, exploring how to fight fires on board, then we’ll look at prevention.

The test

We wanted to start fires in the galley and engine room and extinguish them using the boat’s existing equipment, all of which was out-of-date and needed servicing. To gain an insight into the dangers involved, we decided not to use special fire-retardant clothing, gloves or eye protection. Like every other yachtsman in this situation, I was wearing nothing more protective than oilskins, which are flammable.

Having completed a merchant seaman’s firefighting course in the 1980s, I was well aware of the dangers – not just flames and the rate of spread, but the effects of toxic smoke on visibility and respiration. Our consultants on the test were professional firefighters from the International Fire Training Centre at Warsash Maritime Academy: Martin Lodge, Andy Baynham and Barry Marsh, in full firefighting gear, with breathing apparatus. An emergency fire hose was rigged down the pontoon with an engine-driven pump siphoning seawater.

The Crash Test Boat had one fire blanket and four fire extinguishers: a 1kg foam extinguisher dated 2005 and kept in the galley, and three 2kg powder extinguishers, all dated 2006, one in each of the cabins. We decided to use those for the galley fires. None was suitable for the engine room fire because none had a hose that could be pushed through the firefighting hole in the companionway steps. In fact, the yacht, built in 1982, had no hole pre-drilled through the steps, so we drilled one. Ocean Safety supplied us with some recently out-of-date 2kg powder extinguishers, one of which had a hose attached, and a brand-new 4kg powder extinguisher, also with a hose.

We made two safety modifications to the Crash Test Boat. Osmotech drilled a 5cm (2in) hole in the companionway for an extinguisher hose and a 7.5cm (3in) hole in the bottom of the liferaft locker, above the engine, for a fire hose. The diesel tank was emptied and filled with water to prevent the build-up of vapour. Both fuel filters were removed and the engine oil was drawn off. The engine bay was cleaned and dried. Batteries were removed.

Sea-Fire Europe, which specialises in fire suppression technology, installed its automatic FM200 system for the engine room test. They tested a section of the engine bay’s soundproofing and found it fire-retardant.

Galley fire

Using paraffin as fuel, we started two different galley fires: one in a pan to simulate a fat fire and another using paraffin-soaked toast ignited on a stove-top toaster. We learned a lot from both tests.

Pan fire

Using an extinguisher on this type of fire risks blasting the burning oil all over the galley, spreading the fire and making it more difficult to tackle. Fire blankets are designed specifically to deal with pan fires but they need to be used correctly.

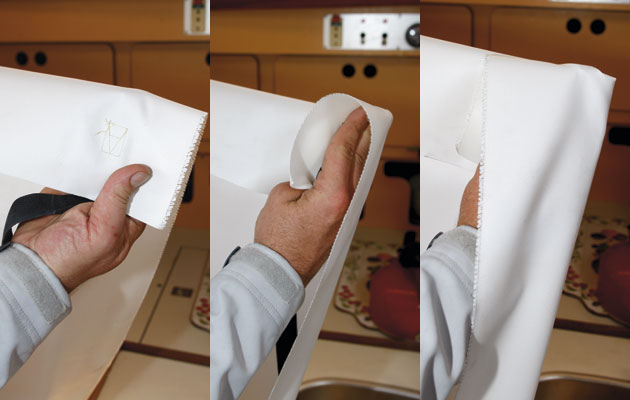

The correct method is to grasp the corners of one edge between thumb and fingers, palms up. Then raise your hands so the blanket touches the backs of your hands and turn your palms away so that the blanket wraps around your hands, protecting them.

Next, making sure you keep the blanket between yourself and the fire. Lay the blanket over the pan, moving from inboard to out. This method doesn’t cool the fire at all, so it’s important to leave the blanket in place for at least 10 minutes, which allows the fire to lose heat. If you don’t want to unpack your fire blanket to practice your technique, use a tea towel.

I was slightly concerned that the edge of the stove was higher than the pan, which meant the blanket would not necessarily prevent oxygen getting to the fire. In the event, I gingerly tucked it in and the flames, visible through the blanket, died out after a couple of seconds.

Toast fire

We used a stove-top toaster and toast soaked in paraffin to start this fire. The plan was

to use a foam extinguisher, then relight the fire and use a powder extinguisher.

Foam extinguisher

Firefighter Martin Lodge told me you should always shake and test an extinguisher before using it in anger. Give it a quick blast to make sure it works. I grabbed the boat’s foam extinguisher, pulled out the safety pin, pressed the trigger and a dribble of brownish water issued forth. This showed the importance of testing an extinguisher and the need to keep all your safety equipment serviced, in-date and ready for use. Safety kit that doesn’t work is worse than useless – it’s dangerous. Had I attempted to fight a fire with this extinguisher, not only would I have endangered myself needlessly, I would also have lost seconds that could be decisive in the battle to get the fire under control.

Martin handed me his foam extinguisher and the paraffin-soaked toast was lit. There was an arc of foam but it wasn’t hosing out with the force I’d expected. I kept waiting for the pressure to build and establish a jet of foam but it never did, that’s not how foam extinguishers work. Inside the canister, firing the trigger releases a foaming agent that mixes with water to form the foam. The foam then forms a layer on the fire denying it oxygen. This breaks the triangle and extinguishes the blaze. Martin also pointed out that I was standing too close to the fire.

Although the pressure of the foam jet was anti-climactic, it was strong enough to knock one of the slices down the back of the stove, where it continued to burn.

After extinguishing the fire on top, I sprayed foam below the stove and the fire was out, but it was an object lesson in how easily fires can spread if fought clumsily.

Powder extinguisher

The powder extinguisher, used on the second toast fire, was far more impressive. It jetted out in a white mist which obscured vision and coated everything with white dust.

It was possible to see the burning toast for a couple of seconds but then a huge cloud enveloped the saloon and I was hosing blindly.

Powder is non-toxic but it gets into the eyes and crunches between the teeth in an unpleasant way so, once the fire was extinguished Martin ushered me into the cockpit. He pointed out that, if you’re absolutely certain a fire has been extinguished, hold the extinguisher upside down and fire it – the gas escapes but not the powder.

Engine fire

We had planned two engine room fires. The first was to be extinguished by Sea-Fire Europe’s FG100M automatic system, which uses the Halon replacement gas FM200. The second fire was to be fought with a 4kg powder extinguisher with a hose aimed through the hole we cut into the companionway steps.

Automatic

The automatic system, installed under the companionway, has a temperature-sensing head that fires at 70°C

The first fire was set using paraffin in a metal pot under the engine. The automatic extinguishing system triggers when the temperature inside the engine room reaches 70°C, before electrical insulation wire or piping starts to burn. As backup, the automatic system had an external manual trigger so that it could be fired should the temperature not reach the required level for automatic firing.

Once the fire was set and the engine bay closed, there was a notable change in the smell and amount of smoke. After about 30 seconds, Martin, who had previously expressed concerns about the Crash Boat’s 30-year-old engine soundproofing (the accumulation of inflammable oil deposits on its foam surface, as well as the security of its attachment), instructed Sea-Fire’s representative, Malcolm McIlveen, to trigger the system manually.

Once triggered, the FM200 should be left in its enclosed space for 10 minutes to continue its cooling effect. However, a minute later the fire was clearly still alight so Martin took steps to fight the fire directly, using carbon dioxide and the foam fire hose – first through the hole above the engine, then by removing the companionway steps.

It took three firefighters about 10 minutes to extinguish and filled the saloon with choking black smoke

‘The paraffin fire was rapidly put out by the FM200,’ said Sea-Fire’s business development manager, Richard Duckworth. ‘However, due to the general poor state of the engine room – not surprising, considering what the boat had been through – the soundproofing collapsed over the engine and its flammable underside ignited. This, combined with the sudden inrush of oxygen when the steps were opened, could well have led to the fire taking hold again. At this stage, the concentration of FM200 would have been too low to extinguish the fire.’

Manual method

Understandably, Martin was reluctant to start a second engine room fire, concerned as he was that the first could possibly re-ignite, so our second ‘firefight,’ a powder extinguisher through a hole, was a bit one-sided.

The effects of smoke

The fire damage looks quite light, but the smoke was deadly. Charring was clear, and she would have been lost if the deckhead caught fire

To demonstrate how quickly a fire can take hold and how much smoke is generated, Martin and his team set a paraffin fire in a small frying pan on the galley stove. Needless to say, the Crash Test Boat’s galley isn’t used. There are no tea towels on the stove rail, no dish cloths, no handy kitchen roll, no matches, olive oil or tin foil – none of the flammable materials one might expect to find in the average galley.

The fire burned for 2 minutes and 40 seconds before Martin and his team decided the deckhead was in danger of catching fire, creating a blaze that could destroy the boat. In that time, the curtains above the stove caught fire and there was heavy charring to the wood veneer inside the coachroof.

In the event of a fire, you should close all hatches to limit the oxygen reaching the fire. We needed ventilation to clear smoke so that we could film and photograph the test. With all the hatches closed, visibility would have been zero with a cloud of thick, black, acrid smoke and oxygen levels would have been very low. Without breathing apparatus, the firefighters would undoubtedly have been overcome.

In many ways, smoke is the most dangerous element in a fire. How do you fight a fire if you can neither see nor breathe? All you can do is get off the boat, alert emergency services and wait for the inevitable.

What we learned

We started this test hoping to learn how to fight fires, how to prevent them getting hold or out of control – or starting at all. It would be easy for you to read the lessons we learned and file it under ‘I’ll get around to it’, but be under no illusion: without Martin and his firefighting team, we would have lost the Crash Test Boat. Indeed, Martin warned us that if the fire did get out of control, the best option would be to sink the boat rather than risk the fire spreading to the pontoon.

Firefighting

Send a Mayday

Fire seriously endangers boat and crew, so have no qualms at all about sending a Mayday. It can always be cancelled once the fire is dealt with.

Forget the mess

Powder makes a mess but fire makes a bigger one. You can’t see anything once powder has been discharged and it’s unpleasant, but it’s non-toxic and can be cleaned up. Fire and smoke will kill you, powder won’t.

Curiosity kills

A fire blanket or powder will kill a fire by removing oxygen. It doesn’t remove fuel or heat, so always wait for at least 10 minutes after the fire is extinguished before inspecting the scene. Reintroducing oxygen could restart the fire, as it seems to have done during our test.

Think it through

Position firefighting equipment where it’s accessible. Don’t put a fire blanket above the stove or even in the galley, and always have a fire extinguisher mounted in a cockpit locker. Engine or galley fires could prevent you from going below.

One hand for the ship

Ideally, choose an extinguisher that can be used one-handed. At sea, you will need one

hand to steady yourself while firefighting.

Keep your distance

Stand well back from a fire: 2m (6ft) at least, and fight from as low a position as you can. Standing too close means the pressure from a fire extinguisher could spread the fire as well as exposing you to flame, smoke and powder. Fighting from a lower position should keep you out of the worst of the smoke and clear of any fireballs, like the one we saw when extinguishing the last galley fire.

Worse than useless

Don’t let this happen to you. Keep firefighting kit serviced because when you need it, you really need it

Keep all extinguishers regularly serviced. You may never use them but if you need to, they must be charged and in working order. If I’d had to fight a fire with the feeble dribble produced by the Crash Test Boat’s foam extinguisher, I would have lost the battle and put myself in considerable danger.

Prevention

Put it out

Never leave any flame or very hot item unattended – stoves, candles, soldering irons.

Get alarmed

Fit smoke, gas and carbon monoxide (CO) alarms and test them regularly. For the engine room fire we were hoping to test the Flame Spotter, an alarm system that alerts you to the presence of flames over 25mm high in two or three seconds. It ‘spotted’ a cigarette lighter flame in a preliminary test and the UK’s lifeboats have had them fitted for a decade. However, after nearly losing our Crash Test Boat in the first engine fire, we took Martin’s advice and abandoned a second test.

Maintenance

Maintain fuel, engine, electrical and gas systems regularly and thoroughly, and regularly inspect soundproofing for cleanliness and secure attachment. Make sure your engine bay is sealed and that the soundproofing is flame-retardant and securely attached. Make sure there are no wires running over the top of the engine.

Automatic extinguishing

Seriously consider an automatic system in the engine bay. If you decide not to, make sure there’s a firefighting hole with a cover you can remove and replace in the companionway and a powder extinguisher with a hose nearby. Opening the engine bay feeds a fire with oxygen and will make it worse, but you can investigate smoke using the firefighting hole as an inspection hatch.

How accessible is your fuel shut-off?

Make sure you can cut off fuel and gas supplies from the cockpit. Going down below might not be an option. We discovered that the Crash Boat doesn’t have a fuel shut-off switch at all. Had we not taken the advised precautions, the engine fire could have shattered the primary fuel filter’s glass bowl and left a tank’s worth of diesel streaming into the engine bay, literally adding fuel to the fire.

Which extinguisher do I need?

There are six types of fire extinguisher available for marine use, but different fires call for different extinguishers.

Water extinguishes fires by neutralising heat. It can only be used on Class A fires, so it probably doesn’t justify a place on board. A bucket over the side would work just as well and it’s cheaper.

Powder is the most multipurpose extinguisher. It coats the fuel, denying it oxygen, but it doesn’t cool the blaze so reignition is a possibility if the fire is disturbed.

A fire blanket works by preventing oxygen getting to the blaze, so extinguishing the fire. It’s important that the blanket covers the pan completely, to prevent oxygen reaching the fire.

Foam, or AFFF (aqueous film-forming foam), is water mixed with a foaming agent. The foam spreads over the fire and denies it oxygen, thus extinguishing it, but it doesn’t cool the blaze.

Carbon dioxide extinguishers work by preventing oxygen getting to the blaze, but take care not to blast the fire from too close, which could spread the flames. Used in a confined space, suffocation or unconsciousness is a risk.

Halon, in the green canister, is a CFC and now banned. It has been replaced by FM200, in the red canister

The use of Halon 1211 extinguishers (the green extinguisher) was banned in the UK in 1993, followed by Halon 1301 in 1999. All Halon extinguishers were required to be decommissioned by 2003. FM200 (in the red canister) is a Halon replacement, suitable for confined spaces such as engine rooms. It doesn’t displace oxygen. It’s also used as the propellant in asthma inhalers. FM200 chemically reduces heat. There are hand-held FM200 extinguishers in the USA, but it’s not coded for portable use in the UK.

What size do I need?

Powder extinguishers are measured in kilograms, reflecting the weight of the powder, and foam extinguishers are measured in litres of stored pressure volume. A 2kg powder extinguisher (around £30) will give you about 7 seconds of firefighting, which is a reasonably long time for anything but an engine fire. Prices for 2 lit foam extinguishers start at around £20.

Other tests in the Crash Test Boat series