Building your own bespoke weather forecast is the best way to get reliable weather updates so you can make better decisions at sea. Toby Heppell finds out how the experts do it

A weather forecast can be flawed.

Weather forecasts online, on an app or from the Met Office via VHF radio, are all subjective.

Inshore waters or shipping forecasts are limited by brevity, large areas and a high degree of caution – they often forecast stronger winds than you may experience.

Mobile apps lean towards forecasts for specific locations and so don’t give you the big picture.

Some are created for specific purposes such as surfing or farming and have a level of interpretation.

Without access to the algorithms behind them, however, it’s almost impossible to work out what the built-in bias may be.

Often these forecasts are accurate, but sometimes they will be wrong.

Skills to build you own weather forecast

If you’re using someone else’s weather forecast, you won’t know the reasons why it was inaccurate.

Expert navigators and meteorologists build their own weather forecast so they are in control of the subjective elements or variables.

Learning to do this means you can judge if a forecast is accurate or reliable, and make your own informed weather forecasts for the precise route and time you plan to sail.

GRIBS are a useful and cost-effective tool for personal weather forecasting

If you get it wrong, you can learn from your mistakes and make better informed decisions about when to put to sea and what conditions to expect.

To do this, you’ll need to be able to access and read GRIB files (Gridded Information in Binary).

GRIB files have been around for years, but are always getting more accurate.

Read them, and get an idea of the broad weather picture.

You will need to interrogate high-resolution GRIB files for problem spots using your understanding of local weather effects.

You then have to compare this overall picture to other sources of forecast to judge your assessment. This is a skill that takes time to hone.

But develop your skills over time and you will be able to make expert-level judgments about the weather, and know how to judge which weather forecast you can trust or not.

About GRIBs

GRIB files are output direct from Numerical Weather Prediction programmes and can provide a very useful and cost effective tool for personal weather forecasting.

Most of us use GRIB data to some degree, as it is from these computer-generated models most forecasts make their predictions to a greater or lesser degree.

Remember GRIB data is purely objective – something to consider when building your weather forecast

It is worth noting at the outset that GRIB data is purely objective as the information arrives to you without any human assessment, quality control nor guarantee that it is even correct – computer and communications systems can and do fail from time to time.

For short-term use it is essential to view them in the context of GMDSS forecasts that benefit from expert assessment of the computer predictions.

You can easily argue that a GRIB file does not provide a forecast, as there is no interpolation of the data provided.

A wise sailor will always take in as much information as possible before choosing to put to sea.

Planning ahead to get the most accurate weather forecast

But by getting into the habit of downloading and reading GRIB files you can be better equipped to understand the stability of a weather forecast and how conditions are likely to change.

‘I think the main benefit to me of GRIB data is the ability to plan ahead,’ says Frank Singleton, forecaster and author of the Reeds Weather Handbook.

‘That is best done by looking at the overall pattern being shown by the files, rather than the wind at points.

‘Looking at that overall pattern via GRIB files is the best way you can understand how the weather might change over fairly small distances – and by that I mean 30-40km rather than 4-5km.

Building your own forecast will inform your precise route and time you plan to sail

‘I take one model, usually GFS, and look for consistency from one day to the next. To my mind, that is the most useful way for a sailor to decide whether you can plan ahead or not.’

This is a point echoed, to some extent by author of the Mariner’s Weather Handbook, Steve Dashew.

‘It is absolutely a useful thing to be looking at weather a long way out and see what it is doing. Today we are lucky that we can sit at home with our computers and look at systems as they roll across the world. It’s worth noting that this is all quite fun to do, too.

‘It’s good for your forecasting to get into the habit of watching the GRIB files as they change to give you an idea of what the wind is doing on a large scale. It is worth stating, though, that what you see on your barometer and out of your window are the key things when it comes down to weather on a boat.’

‘GRIB files essentially offer the same information as the synoptic charts, so in many ways when you are using low resolution GRIB file, you use it in the same way that you are using a synoptic chart,’ adds weather forecast guru, Chris Tibbs.

‘The GRIB files are rather easier to look at than synoptic charts, I am adamant that people should be using GRIB files. We have moved on from the days of measuring isobar distance and then guessing at what the winds would be, simply because GRIBs do that for us and it is so much easier to see it and understand it in GRIB format.’

Weather forecast models

There are many weather prediction programmes running across the globe, to which most sailors can get varying degrees of access.

The best know is the American NOAAA Global Forecast System (GFS).

Alternatives are the CMC GEM (Canadian Global Environmental Model), the US Navy NAVGEM, the French ARPEGE and the German (DWD) ICON.

Choosing one model will help you make comparisons making it easier to plan your sailing

There are many others, of course, but these are generally either unable to be accessed easily or are not provided for free.

These various programmes all provide slightly different forecast models, and big forecasting bodies like the UK’s Met Office may use an amalgam of any number of these models to create their forecast.

However, for most, choosing one model and sticking to it offers the easiest solution over trying to make comparisons.

‘Typically the models tend to converge in terms of prediction at something like 3-4 days out,’ says Singleton.

‘But even in the short term where they might diverge there is not that much to be gained from comparing them.

Determining reliability

‘For a sailor looking at a GRIB file, you are trying to determine the reliability of the weather to come, not the reliability of the prediction model being used.

‘I am always looking for consistency of the prediction from one day to the next to decide how accurate and so believable it is.’

Of course if you are going to be downloading GRIB files then you are naturally going to be faced with a choice over which model to select, so is there any significant difference between one another?

‘As far as I am concerned there is very little difference between them,’ says Singleton. ‘I tend to use GFS as it is the easiest one to find.’

Localised storms and squalls are not served well by GRIB files, which look at the conditions as a whole, so will need local interpretation

The American GFS model has been upgraded in recent months, to bring it slightly more up to date, where some considered it a little behind some of the European models.

In reality, however, these modelling updates are occurring pretty continuously on all the systems and will have very little discernible affect on the output for the casual user, as Singleton explains:

‘If you were doing some very sophisticated modelling then you might see a difference when models are updated but day-to-day weather is so unpredictable, for a wind forecast you are not going to see any difference.’

Where there is a slight difference between models is in the time of their release, however. Almost all of the models provide a new file every six hours.

‘The German model runs every three hours, so in theory that will often be the most recent forecast but in terms of weather I am not sure that higher frequency makes any significant difference,’ Singleton concludes.

Limitations of a GRIB file for weather forecasting

The principal drawback with a GRIB file is that the global files only provide data on a grid of roughly 10km. As such, they are not all that useful in terms of specificity.

You can, however, download high-resolution files (often for a subscription fee) that reduce the grid to 1.4km. These are better for providing more accurate information for a specific area.

The downside to this, of course, is the significantly larger number of files you will need to download for any given passage.

The distances involved in the global scale data also lead to a common misconception surrounding the GRIB forecasting, that they have a tendency to under-read the wind, but this is not the case.

The Strait of Dover is a well known wind acceleration zone

‘With global models and with a grid length of 10km, if you are calculating on a grid of that size then the calculation on that grid is smoothed somewhat,’ explains Singleton.

‘Although the forecasts are probably pretty good at predicting the mean or average windspeed they do not do well on the extremes. So if I am crossing the channel and the model says a Force 4-5 then I am pretty sure that at some point on that passage I’ll probably get a wind speed of Force 6 and/or 3. So there will always be quite large variation in that – as we know the weather varies tremendously.’

Similarly, because of this smoothing effect GRIBs do not do well with local weather effects.

A global GRIB file may well tell you that the wind will be a Force 4-5 across the Channel, but in a southwesterly, you would expect that windspeed to increase as it accelerates through the Dover straight but be more accurate in the West Country.

As such, a Force 4-5 might well mean Force 6-7 for a Dover crossing, where Force 3-6 is the more likely when going from Dartmouth to the Channel Islands.

In addition to this struggle with land-based effects they are not all that good at reacting to specific weather anomalies.

‘Tropical storms are not very well modelled by GRIB weather files,’ say Dashew. ‘You can often see them start to form in terms of the overall wind picture and direction as it begins to build but as they are pretty quick to form, a very stable picture can become unstable much more quickly than the six-hour GRIB models can cope with very well.’

The human factor in building a weather forecast

Whilst a lack of interpretation is one of the drawbacks to using GRIB files to build a weather forecast, it can also be seen as one of its positives.

‘Forecasts are inherently political,’ says Dashew. ‘They are the result of people perhaps getting it wrong at some point so some pressures to interpret them in a different or more conservative way very often. These pressures change all the time so they are often subject to outside factors.’

Singleton says he understands how pressures on forecasters can lead to this opinion being formed: ‘In my days at the Met Office when the Shipping Forecast used to work under me, they always said they try to tell it like it is and they do not try to make it sound worse.’

Over forecasting

‘A forecaster in the UK must issue a gale warning if the wind might reach Force 8 for that area, anywhere in the sea area.

‘That might only be a part of the sea area, but on the shipping forecast, there is not the time (and in the inshore waters forecast the space) to define that level of specificity, so they might say ‘round headlands’ or give as much detail as they can that way, but it will still be a little unclear.

‘That can provide an impression of over-forecasting.

The Shipping Forecast covers a whole sea area so you may need to factor in local interpretation when building your own bespoke weather forecast

‘Also, the forecaster can only cancel a gale warning if they are sure there is no chance of there being one in that sea area.

‘So if you put that together this naturally leads to an appearance of over-forecasting,’ adds Dashew.

Though it might still be broad-stroke, a personal interpretation of the GRIB data allows you to see if this gale is likely to be making its way in one direction or another.

The differences in forecast and GRIBs are not only political, as Singleton touches on.

A specific weather forecast for a specific purpose

Many forecasts are designed for specific purpose.

The Shipping Forecast, as noted above, necessarily needs to be both brief and geared towards safety in terms of top-end reading.

As such, it is prone to predicting the possibility of a gale where there might, in fact, be none as a result of erring on the side of caution and not having the time or space to provide a truly in-depth picture.

Elsewhere other forecast tools take in GRIB information and run it through a proprietary model to achieve a goal.

Singleton points to some forecasts which are often used, which make very coastal specific forecasts.

These can be very accurate for picking up sea breeze and other factors as they are variables added on top of the GRIB information received.

Learning to distinguish between forecasting models

This is useful close to shore but if you are making a long passage and are 10 miles offshore, their prediction will be taking into account effects that will have little bearing on your forecasting.

Without knowledge of how different forecasting models prioritise certain factors, it can be hard to know whether the information provided is going to be accurate for you.

GRIB files simply lay out the prediction with nothing added and nothing taken away, which allows you to be in control of what factors you should consider on top of this standard information.

Continues below…

Heavy weather sailing: preparing for extreme conditions

Alastair Buchan and other expert ocean cruisers explain how best to prepare when you’ve been ‘caught out’ and end up…

How to avoid collisions in fog

Not many of us would happily set sail in fog but sometimes it is unavoidable, and knowing how to avoid…

Weird weather – is cold wind heavier than warm wind?

For a given wind speed, do you heel more in winter than in summer? Yachting Monthly asked Crusader Sails' Paul…

As they are essentially apolitical then GRIB files, driven purely by data, can allow for some decent analysis to allow you to form an opinion.

‘One thing that is really good about GFS is that you can now access information on the accuracy of the data as compared with the real-world information,’ says Dashew.

‘So you are able to look at the historical GRIB information for an area and match that up with how accurate the forecast was.’

Again, this purely data-driven approach that all the models take, without any human interaction makes for a much more transparent forecasting tool.

Using a weather forecast model to your advantage

‘Let’s say I’m planning a Channel crossing from Dartmouth, then I would start to look at GRIBs from around five days out,’ says Chris Tibbs.

‘At that stage, as I am at my computer at home with broadband – so no issues with bandwidth – I will take a look at a file of the whole Atlantic.

‘Broadly what I am looking at is the way that systems are forming and direction of travel out in the mid-Altantic.

Tide and wind acceleration must be considered when planning a passage past Start Point

‘One thing that lots of readers will do – I tend to use Predict Wind’s Offshore App – is to animate files and I think that is a really useful tool so you can see how the fronts and systems are shaping up and how they are developing over time.

‘Once I have a good idea of what broadly is coming my way, I would be looking to get some high-resolution files for specific sections.

‘It’s a three-step approach, effectively. You have the coastal waters on the English side first.

‘So I would look at things like Start Point in high resolution and be looking at what sort of acceleration you will be getting there and considering the tide and whether that will add to any wind acceleration.

‘It might be worth looking at something like Wind Guru or some other coast-specific forecast to see if that is predicting any sort of thermal enhancement.

‘Then the further offshore you get, the more GRIB files’ accuracy increases as they are not dealing with the land effects, so I’d be focusing on them and what I expect to come in based on what has been developing in the Atlantic.

‘Finally for the other side of the Channel I would once again be looking at high-resolution files again comparing them with a coastal waters forecast or similar for that side to see if they are matching what the GRIBSs suggest and what I expect.’

How to read a GRIB file to get the best weather forecast

Colour is added by software to give an easy visual guide to wind strength. Blue is light wind, through green and yellow to strong wind areas in red

While looking at a GRIB file may seem intimidating at first, deciphering one is actually very simple.

Knowing how to use wind patterns to your advantage or find a suitable weather window is a different story.

By familiarising yourself with how to read GRIB data, you can better prepare yourself for future passage making and sailing in general.

Wind barbs

Wind barbs indicate both the wind speed and wind direction.

The barb line represents wind direction by pointing like an arrow in the direction the wind is blowing in.

The tails extending from the barb are an indication of wind speed; each half bar represents 5 knots of wind.

Therefore, in this GRIB file, the strongest wind is NW at 40 knots and the lightest winds are the variable direction barbs of 5 knots.

A triangle barb would indicate 50 knots.

A singular dot or circle within a dot represents calm conditions. Interpreting GRIB data is simple, yet the information can be extremely valuable.

Chris Tibbs on local wind effects

All the time we are getting access to higher and higher resolution GRIB files.

So GFS now offers ¼ degree resolution [one weather point every 15 miles] for the global model.

A decade ago that sort of accuracy would have cost a lot of money and was not really attainable for the ordinary sailor, but now it is free, or often on a very affordable subscription for the highest resolution.

That said, we are always going to have local differences that are simply not picked up by GRIB files at the moment.

That often depends on what the local effects are, some are dealt with quite well, others less so.

Fronts

If you have a fairly active front, it is pretty safe to assume the front will give you a more abrupt change in the wind direction than that being shown on a GRIB file.

Most sailors will have experienced the very sudden change in windspeed and direction you get as that front arrives.

The GRIB files, however, will usually smooth that out over a number of hours.

The prediction it gives for the front coming over and the subsequent change will be accurate, but it will not show how sudden that change will be.

Sea breeze

Sea breeze is an area where you have to make a judgment about the complexity of the situation.

The sea breeze in the Solent is different to a few miles down the coast in Brighton, for example.

The Solent sea breeze is famously complicated, coming separately from either side of the Isle of Wight, and that complexity is unlikely to be picked up, so you do need to use your own skill and judgement to determine what you think is going to happen.

Forecasting accurate sea breeze in the Solent is tricky due to it being a relatively small strip of water between two pieces of land

Much of the problem comes down to what the GRIB models see as the land or sea mass.

The Solent models struggle with the relatively small piece of water between two pieces of land.

The models tend to smooth out the differences across that area, so you can see the sort of scale where land mass can have an effect without the models picking it up.

Storm cells

Something else that GRIBs really do not pick up are things like thunderstorms, or smaller clouds, as they are too small for the scale within the model.

It will pickup a cold front, which you might assume would bring the possibility of showers on that front, but it won’t pick up wind effect of things to do with clouds and showers.

Rainfall

If you’re using GRIBs to get your forecast, and you see a very active front due to arrive, it is a good idea to then turn to an inshore waters forecast or the Met Office (or similar) to see what the rainfall prediction is.

That rainfall prediction can be quite accurate in short-term forecasting and will provide a better idea of the time that front is likely to hit and so the time you are looking for the wind to change abruptly, as it will arrive with the rain cloud.

Headlands

Depending on how big a headland is, GRIBs will struggle here too. It is easy to check this ahead of time.

If you look at the GRIBs files historically, you will be able to see whether there is any bend being predicted round a headland.

All headlands will have some acceleration effect and some wind bend effect, so if the GRIB file never picks this up, irrespective of true wind direction then you know it is something to look out for.

Tidal acceleration

Finally, clearly tide will not be factored into any of this and can cause a significant increase in apparent wind.

Again, round a headland where the tide is accelerating, the combined effect can be up to 15 knots wind speed increase.

If the headland is too small to be picked up by the GRIB files and you are going to have the tide underneath you, that is going to account for a significant discrepancy.

Getting hold of GRIB files to build your weather forecast

Ultimately, GRIB files are created by a wide variety of bodies throughout the world, including governments and research centres.

The information is provided essentially in the form of code, so you do need some sort of programme with which to open the file and turn the code into the graphical GRIB format.

Predict Wind is popular with sailors building their own weather forecast

Many of these are publicly available for free, but others are not or require some form of payment.

The UK’s own GRIB files, for example, cannot be accessed for free.

Given that all the different models model the weather globally then this is of little concern.

Although there are forecasting differences between them it is almost impossible to say that any one model provides greater accuracy than any other specific model.

A choice of models

There are many options for sailors to use and for many, which particular option they plump for to build their own weather forecast, will likely be a matter of personal preference.

However, given GRIB data is largely provided free, there are few situations where it makes sense to pay per download.

Predict Wind

Predict Wind will likely be familiar to most sailors for their forecasting software.

Should you wish to go further afield, however, you can download Predict Wind Offshore and add GRIB files.

The application works well and seamlessly with most satellite and SSB comms tools, by simply downloading the data file, which can be opened in the application.

Predict Wind’s weather app is very user-friendly and the same is true of the Offshore app.

It’s easy and straight forward to download GRIB files and store them for later use.

One key drawback, however, is that it only allows access to the GFS and ECMWF files.

These are, admittedly, two of the most popular but it would be nice if there were a wider range of options out there.

For more information, visit: predictwind.com

XyGRIB

XyGRIB is an open-source piece of software, which you download to your computer, and provides a simple-to-understand way of downloading GRIB information.

It’s a great viewer for high-resolution data and includes a number of useful features.

These include the ability to change the way in which the maps are displayed and your own bespoke colouring for varying wind strengths etc.

XyGRIB provides access to a wide range of weather models including GFS, GEM, NAVGEM, ARPEGE, and ICON.

For more information, visit: opengribs.org

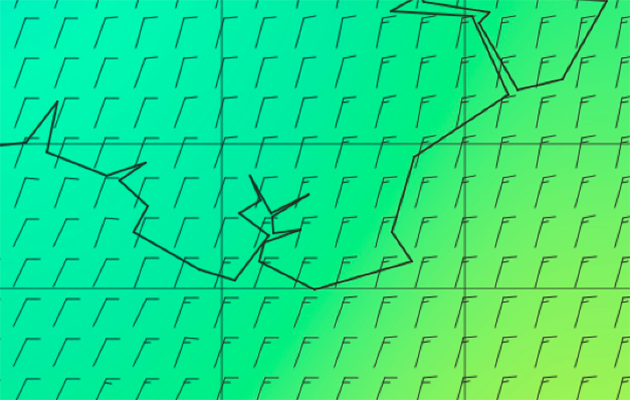

Using GRIBs to plan an English Channel crossing

1. Above we see a low pressure system developing out in the Atlantic (the dark blue west of N Spain) with the building SW wind denoted by the tongue of yellow across Brittany.

A high is forming further to the south west.

2. Two days later this system has arrived in the West Country so we know if we are setting off at the end of the weekend into the early part of the week we can expect building wind with it backing to the south.

3. Our higher-definition file is showing little wind deflection round Start Point but we would expect to see some around the headland with this direction.

It also shows no increase in wind speed, which we would also expect.

Seeing this it will be worth building into your forecast that there will be acceleration here that is not being reflected in the file.

4. Here the increased wind is shown around the Start Point area, but the GRIB is still not showing any significant deflection or increase in speed.

Looking at further days either side, we are able to see that there is rarely any appreciable land effect included in the file, but knowing that the headland is definitely big enough to increase wind speed, we need to consider this effect coupled with the increased wind arriving in the early part of the week.

Enjoyed reading this?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.