James Stevens stands by as Nikki Abbott tackles her first night pilotage as skipper

How to plan and execute night pilotage

James Stevens, author of the Yachtmaster Handbook, spent 10 of his 23 years at the RYA as Training Manager and Yachtmaster Chief Examiner

When I started skippering, one of the hardest skills to master was pilotage. It became easier with practice but then came the time to tackle pilotage at night.

My first night entry was Plymouth. It looks pretty easy on the chart: a huge bay with a couple of rivers flowing into it and plenty of navigation marks. In the dark, the plethora of flashing lights made navigation really confusing. The city of Plymouth and the fun fair on the Hoe were bathed in dazzling light whereas objects that might have been helpfully illuminated, such as the breakwater across the entrance, were inconsiderately pitch black.

Occasionally harbours are easier to enter at night than in the day. Langstone, which is rarely visited by most yachtsmen, has a large expanse of water with channels that can be difficult to pick out by day. At night the absence of background light makes finding the marks much easier, but such places are rare. Most harbours are populated to some degree and require good planning and pilotage skills to enter successfully after dark.

Night pilotage problems

From a yacht, the identification of buoy lights is difficult because they are at the same height as the navigator’s eye when standing in the cockpit. They become lost amid the background scatter of lights and one can easily miss a mark and cut a corner, which risks a grounding.

It is also difficult to judge distance at night. For the beginner, lights on the shoreline look much closer than they are. It’s a difficult skill to learn. Even experienced navigators struggle to judge distance off at night.

Stay on deck

As always with pilotage, the right place to be is on deck, not least to avoid uncharted objects such as other craft, mooring buoys and fishing pot markers. Most pilotage errors occur at night rather than in the day so a thorough pilotage plan is essential. Even with a navigation station filled with electronic aids it is still possible to become disorientated while trying to reconcile the view on deck with that on the chart. You need a pilotage plan.

The most important principle is this: if you know the position of the yacht and you are armed with a chart (electronic or paper) and a compass, you know the range and bearing to the next mark. This means that when you reach a known position, such as a navigation buoy, you know where to head to find the next one. Simple, except that a surprising number of navigators waste time scanning the lights ahead with no plan to find the one they want.

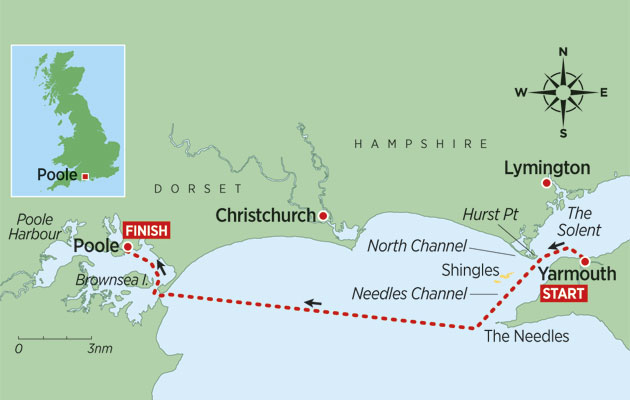

To understand what it feels like to skipper a yacht in a complex harbour at night for the first time, Yachting Monthly asked Nikki Abbott, a Day Skipper, to take a 34ft yacht from Yarmouth to Poole on 14 April 2015.

Nikki Abbott

‘When I agreed to sail with James for this night passage, I immediately became extremely nervous,’ said Nikki Abbott, 20. ‘Whilst I have sailed many times in the past, this would be my first time skippering at night and being in complete control of the boat, crew and pilotage.’

Nikki lives in Surrey and works for a recruitment company. She first sailed at 16 as crew with the Rona Sailing Project and became inspired by how much the experience taught and helped her. Since then she has sailed nearly 5,000 miles as a volunteer with the Rona Sailing Project and other sail training charities. She enjoys working with young people and adults, teaching them the basics of sailing and developing their life skills such as teamwork, understanding and tolerance. She has taken an RYA Day Skipper practical course and is now progressing through the RYA training scheme with financial assistance from Trinity House and the Association of Sail Training Organisations.

Night vision

Peering through the dark is much more effective if your eyes have adjusted to night vision. This takes 15 minutes in dim light and one flash of a torch sends you back to minute one. Wearers of photochromic specs with lenses that darken in bright light should note that the enquiry into the loss of the yacht Ouzo discovered that they can reduce night vision by 20 per cent. Merchant Navy personnel are forbidden to wear them on a bridge at night.

Extra checks and kit for night sailing

Before we left Yarmouth, our pre-slip checks revealed a dud port nav light bulb, which we replaced. Good job we checked!

Check the nav lights work – we had to replace a bulb

If you have lifebelt lights – check they’re in working order

You need a powerful torch for identifying buoys, lobster pot floats and illuminating sails to help prevent any collisions

Nikki wore a red headtorch to keep her night vision while reading pilotage notes on deck

Keep a couple of small torches for searching in lockers. I use clockwork ones

Fit a red-filtered chart table light, and ideally one over the galley

Dim the plotter and instrument screens

Check your main compass and instrument lights are working

A hand bearing compass with built-in light, usually fluorescent, is essential for identifying marks

You’ll need a pair of binoculars, preferably with built-in compass light to make sure you’re looking along the right bearing

Make sure your lifejackets have a built-in light, crotchstraps, a sprayhood, and tethers you can clip to a jackstay

Have some pre-prepared snacks in the cockpit

Keep everything tidy below so you don’t need to turn on the cabin lights to find out what you’ve just tripped over

Entering Poole at night

Entering the huge expanse of Poole Harbour is tricky enough by day. At night it’s a real pilotage challenge

At the narrow entrance to Poole Harbour, two outer channels and three inner channels converge – add to that the bright lights of Poole, a chain ferry and a cross-Channel ferry terminal and that’s a lot of lights!

There are two channels to the harbour entrance: the main Swash Channel, well marked with pairs of buoys, and the smaller, shallower East Looe Channel that runs north of Hook Sands and creeps along the beach past some of the most expensive real estate in the world. Arriving from the east, the East Looe Channel is the quicker option and avoids a couple of miles of ebb in the Swash but it is harder to pick out at night, and requires a tidal height calculation.

Once inside the harbour there is a chain ferry to negotiate and, at certain states of the tide, a ferocious stream. There is no shortage of buoys where the channel splits at the harbour entrance and you have to be well prepared to pick the right one.

After the starboard turn near the entrance, the channel then curves to port as it heads up to the docks and Poole Quay.

Confusingly there are two lit channels up the harbour, the one closest to the shore used to be the shipping channel but this is now for smaller craft. It is still well marked but confusing the two and trying to cross over almost always results in grounding on the mud.

A low-lying, heavily-populated shoreline makes it very difficult to identify, or even see, buoyage at night

Poole Harbour’s north shoreline is heavily populated and very bright at night. There are frequent ship movements and hundreds of leisure craft, most on moorings but some moving. There is a boat channel just outside the port-hand markers of the Middle Ship Channel, and that will keep you out of harm’s way. As you near the brightly-lit docks it is easy to lose the channel.

Planning the pilotage

GPS makes a big difference. If you know where you are, you know the range and bearing of the first mark, and your pilotage plan does the rest

When approaching any harbour you need to have a good idea of what to look for and where to look for it. Fortunately GPS has taken the sweat out of finding the yacht’s position so it is easy to know where to look for the first mark (you do, of course need to know its light character). Binoculars with a built-in compass are useful here. From the first mark, the pilotage plan will tell you the range, bearing and light character of the next.

You should know the height of tide, the clearance if required and the direction and strength of the tidal stream. The pilot book will warn of hazards such as the chain ferry and how to identify when it is under way. The more you pre-plan the more time you can spend on deck. Conversely, poor navigators wear out the companionway steps trying to relate reality to the chart.

In a complex harbour such as Poole there are going to be times when finding the next mark is not as easy as it looks on the chart. Slow down and keep an eye on the echosounder to stay in the deeper water of the channel.

Challenges like entering Poole at night happen at the end of a passage, with skipper and crew tired after a day or more at sea. It is the time you have to concentrate most, but there is a great sense of achievement when you are safely alongside.

First time skipper’s thoughts

The plan was to sail on Tuesday 14 April, leaving Yarmouth on the Isle of Wight in early evening and arriving at Poole Quay Boat Haven at night, so I spent the previous few days checking tidal times, heights and streams, and preparing my passage plan. I’d also been checking forecasts for the last week.

When I met with James in Yarmouth, he was happy to help but I felt nervous that he would spot a hundred errors in my passage plan! That slightly nauseous feeling only increased when I stepped aboard his beautiful Hallberg-Rassy 34 Tamora, and realised I was taking charge of his pride and joy.

Checking the plan

We relaxed with a few cups of tea and discussed my plan, focusing on the Poole pilotage. I’d already drawn up a rough sketch to have on deck with me, which noted the key marks and each buoy’s light characteristics. I knew that, unlike daytime navigation, it wasn’t going to be easy to spot the next mark and join the dots through the harbour. To help identify the next mark, I added in a few key headings so it would be very clear very quickly if I’d turned us at the wrong mark. I also made a mental note of which marks were important for deciding when to change course.

We discussed other potential issues, such as encountering large shipping in the harbour’s Middle Ship Channel, and the safest place to move out of the way, in this case the Boat Channel.

To enter to Poole Harbour, we could use either the East Looe Channel or the Swash Channel. I decided, given we were approaching from the East in a small vessel, the East Looe Channel would be the better as it also had the advantage of avoiding shipping in the Swash.

Is there enough water?

It was vital to check the depth as the East Looe Channel is 1m at chart datum, and Tamora has a draught of 1.9m. I was confident that we would have enough water at all states of tide – it would be fairly close at low water (LW Poole was 1m at 0147 on Wednesday 15 April) but we should be alongside by then.

The forecast was for very light winds, so we could be a little more adventurous, but I made the decision that past a certain time we would use the Swash Channel instead. We had plenty of time to reach Poole before LW however, so it wasn’t a big concern.

Threading The Needles

Another key part of the passage plan was negotiating the Needles Channel, crucially timing it so that the tide was not against us as it can be extremely powerful. I used the Almanac to locate Portsmouth HW times and used a tidal stream atlas to ascertain that the earliest time to arrive at Hurst Castle was HW-1, which for us was 1954 BST. As Yarmouth is so close to Hurst, I planned to slip the lines around 1930.

Early forecasts said that fog patches were possible so we prepared a plan for low visibility. For instance, my plan was to sail through the Needles Channel but if the fog was thick at Hurst, I would switch to the North Channel to avoid shipping.

How Nikki planned her passage

The nightsail

After dinner, my thoughts turned to the daunting task of organising Tamora’s departure. I have over 5,000 miles in my logbook, but less than 50 as skipper, so I have very little boat-handling experience. Fortunately, the wind was light, the tide negligible, and James’ expert opinion was on hand. After a gentle stern spring off – a surprisingly relaxed departure for me – we were on our way.

Despite calm conditions, there was surf crashing ominously on the Shingles Bank north of Needles Channel

Having piloted Tamora out of Yarmouth, we motored West towards Hurst and the setting sun. We reached Hurst at 2000 and, before I knew it, I was navigating through the Needles Channel. Despite the breathless conditions, the Shingles Bank was horribly conspicuous with a large swell and breaking waves: intimidating, but easy to avoid!

There was a little mist around so I kept track of our progress and used binoculars to spot the next buoy as the Channel narrows at its western end. I had to be sure that we weren’t off track. Once out of the Channel we headed for Poole and it was a relief to begin the straightforward part of the passage. I had calculated for two hours of fair tide on this 11-mile leg and plotted a course to steer, accounting for it. We all had cups of tea and I kept a careful watch for any hazards such as traffic or lobster pots, which is not so easy in the dark.

Beginning the approach

Nikki checks Tamora’s position and adjusts course 10° to port, towards the entrance to the East Looe Channel

As we closed on Poole, I ducked below to check our GPS position and see if our course needed changing. As it turned out, I had slightly overestimated the effect of the tide and we altered course about 10° to port.

Tamora closes land with the chain ferry behind the port shroud to confirm that this is definitely Poole Harbour

Soon we spotted the lights of the chain ferry at the entrance to Poole Harbour, which was a relief since it meant I hadn’t taken us to the wrong harbour! It also meant that the real challenge was beginning. The sun had set at about 2000; it was now around 2115 and totally dark – the Almanac said the moon wouldn’t rise until 0300.

The first challenge was locating the red and green markers at the entrance to the East Looe Channel, which was harder than expected. I knew that I was looking for one green flash every five seconds, but the second green buoy flashed every three, and it was tricky to distinguish the two, and to judge distance. I knew the bearing to the gate and we were on the correct course, but because I couldn’t tell which green to aim for, we passed it without noticing! Even worse, we left it to port so we were outside the Channel. Luckily we were near High Water (2142 BST) and there was enough water under the keel.

It gave me a huge shock. After feeling confident that I’d spotted my buoy, I’d fixated on the green marker and ignored the red. I felt determined not to miss any more. The next gate was far clearer and I knew the course we needed afterwards.

Reeds Nautical Almanac says the chain ferry shows a flashing white strobe forward when engines are engaged

The fixed lights leading towards the ferry were also easy to find. Initially the ferry’s lights helped as they slightly lit up the area, but car headlights and other white lights on the shore were very confusing as my next important markers were a couple of cardinals.

A confusion of lights

Once past the ferry, I had a moment of panic. There were so many lights around me, as several channels in the harbour meet at that point in an indistinguishable mass of green and red flashing lights. I soon regained my confidence as the cardinals I was looking for, east cardinal Brownsea and the west cardinal off North Haven Point, were different to other channel markers and easily identified. As we turned the corner, I used the distinctive very quick flashing red light of port-hand marker 16 to ensure I knew where I was and that our course was good.

Reds, greens and whites everywhere! Fortunately the white light is the west cardinal off North Haven Point

My next challenge quickly became apparent. There is more than one channel in Poole Harbour, hence several sets of lateral markers flashing against the lights of the shore. Car headlights make an excellent impression of a white flashing light as they pass behind an obstruction and reappear.

The back-scatter of the ferry terminal’s lights does nothing to make the picture any clearer for a small-boat navigator

With my passage plan, I knew the heading to the next mark but I hadn’t noted the distances between marks so I didn’t know when to expect it. I coped with this but it made for tenser pilotage as I was constantly scanning the area around me, unsure exactly where to look.

Trust your plan

I told myself to keep calm and trust my sketched plan. Sure enough, I was able to identify each pair and made sure I was definitely where I thought I was. Making the turn to the east was a big moment as a classic error is to cut the corner. However I knew I was looking for the east cardinal Aunt Betty and I wouldn’t turn until I had spotted the distinctive white light flashing three.

After that corner I was on the home straight! I still had the problem of not knowing the distances between marks so I was furiously scanning the area and counting the timings of various lights. Before I knew it, we had spotted the final south cardinal, Stakes, which was my cue to turn north towards the marina.

Tamora gets snugged down in Poole Quay Boat Haven at the end of a first – and successful – night passage

After successfully meeting my main challenge, I now faced another: bringing James’s pride and joy alongside without a scratch. It was a fairly steep angle into the berth but of course James was on hand to offer advice and despite my concerns, it was a nicely controlled manoeuvre.

Again, I was lucky with the lack of wind and tide. It was a wonderful moment to have a glass of wine and relax at last!

The debrief

Despite lacking boat-handling experience – and having the owner aboard – Nikki’s departure was perfect

Nikki has logged several thousand miles but her only experience of skippering is her Day Skipper practical course and a week with friends in a small bilge-keeler. Taking charge was a big step for her and she was clearly anxious. Still, she gave it her best shot and it all went (almost) according to plan.

She has passed the RYA Coastal Skipper/Yachtmaster theory course, and I couldn’t fault her course to steer and tidal calculations. She also understood the light characteristics, Colregs and other theory so there was no need to refer to any textbooks.

Nikki monitors progress down the Needles Channel, with west cardinal Bridge and the Needles light almost in line

After leaving Yarmouth and arriving at Hurst as intended, at slack water, she planned to pass down the Needles Channel at dusk. She avoided the North Channel because she thought it was harder, although it would have been a shorter route.

The wind was a light SSE that faded to nothing when she entered Poole, with good visibility but the chance of fog. Most of the passage was therefore under power – easy for navigation, but with the risk of wrapping the prop with a lobster pot. We kept a good lookout.

Approaching East Looe Channel, Nikki focused on light character but forgot to use bearing to find the mark she wanted

Ambitiously, she decided to enter Poole by the East Looe Channel – much quicker than plugging the ebb up the Swash Channel, but not easy at night. It’s shallow and Tamora, with 1.9m draught, would be close to grounding at LW, and the weakly lit buoys can get lost in the shore lights and the brighter navigation lights of the main channel.

Finding the East Looe Channel is critical to avoid grounding on the notorious Hook Sands. Nikki shaped a sensible course from Poole Bay but relied on identifying the light character rather than the range and bearing of the light from the yacht’s position. With two consecutive greens, one flashing five seconds, the next three, it’s easy to confuse them and we aimed for the inner one, missing the first. Fortunately although the tide was ebbing, our early start meant there was enough water and once in the Channel Tamora’s progress was well controlled.

Nikki chose to motor down the middle of the Ship Channel, but buoy-hopping in the Boat Channel would have been easier

Nikki chose to navigate down the centre of the Middle Ship Channel – fine on the night because there was no shipping, but it would have been easier to pilot buoy-to-buoy in the Boat Channel. She identified each buoy by its light character and with her pre-planned courses she confidently brought us in. She had a small problem identifying the last buoy against the bright dock lights, and once again it would have been easier to find it from the previous buoy. She was always in safe water and because her course was accurate we found the buoy and headed for the Poole Quay Boat Haven.

Overall, her pilotage was well above Day Skipper level and her careful planning paid off. I have seen many skippers enter Poole at night and struggle in the confusion of lights. Nikki was calm, I felt confident she was in control and, apart from one slip, she knew where we should be and what course we should be on.

As ever with an rookie skipper, her boat handling needs practice, but it didn’t help having the owner on board. Next stop for Nikki: the Coastal Skipper practical course.

Thanks to Adlard Coles Nautical for granting permission to reprint sections of Reeds Nautical Almanac 2015

For all the latest from the sailing world, follow our social media channels Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Have you thought about taking out a subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine?

Subscriptions are available in both print and digital editions through our official online shop Magazines Direct and all postage and delivery costs are included.

- Yachting Monthly is packed with all the information you need to help you get the most from your time on the water.

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our expert skippers and sailors

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment will ensure you buy the best whatever your budget

- If you are looking to cruise away with friends Yachting Monthly will give you plenty of ideas of where to sail and anchor