How would you get back to safety if your rudder was carried away? Chris Beeson tests three jury steering techniques on the water

Jury Steering

Losing your rudder at sea can be a terrifying business. The trusty little ship in which you’ve invested love, time and money, and which has kept you safe and protected from the sea, is suddenly at its mercy. Unable to hold a course in any direction, she lurches blindly and ever deeper into danger. What happens next is down to you.

Will you, like the two-man crew of the Sadler 25 Star Fire II, in 2009, improvise a successful jury steering system and safely sail on another 1,700 miles to St Lucia? Or will you, like the crew of F2, a Hunter Legend 450, in 2002, be forced not only to abandon your yacht, but also to scuttle her, to prevent her being a danger to shipping?

In this situation, you’re probably aware that there are certain strategies designed to get you home, but how many have you tried? Which, if any, is best for your boat? We put to the test various methods recommended by the textbooks.

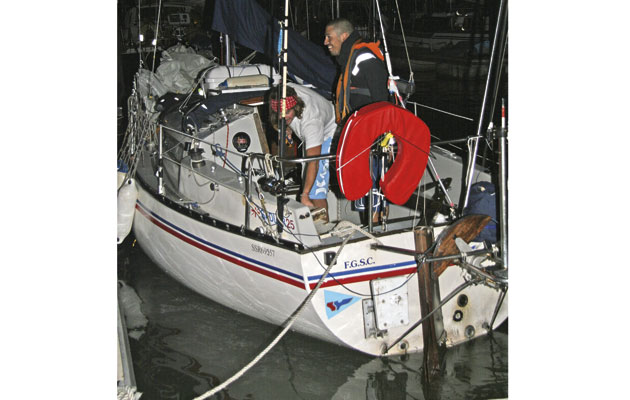

Simon Judge volunteered his Westerly GK29, Growling Kougar, which has a transom-hung rudder. Before setting off from her home in Cowes, Simon (left) and his crew Andy Buchanan, both police officers on the Isle of Wight, unshipped the rudder

The test

The jury steering methods we wanted to look at were:

- Sail only – trimming the sails and using crew weight to steer the boat by trimming the hull

- Jury rudder – fabricating a jury rudder from materials that would be found aboard most modern cruising yachts

- Drag steering – using a drogue, or a bucket, off the stern to steer

We decided that a successful system would be one that allowed the yacht to sail straight courses at 50° and 120° to the apparent wind. If successful on those points of sail, we would then find out how well the system performed at other, more challenging wind angles.

For our test, just west of Cowes in the Solent, we had a 10 to 12-knot north-northeasterly breeze and a slight sea state. These were relatively benign conditions and suited our purpose perfectly.

The kit

We brought along a spare spinnaker pole, loaned to us by The Rig Shop (www.rigshop.com), so that we didn’t risk damaging Growling Kougar’s pole during testing. We also brought a section of marine plywood, pre-drilled, so there was no need to remove any of the yacht’s panels, lockers or doors.

We brought 100m of nylon three-strand mooring warp, courtesy of English Braids (www.englishbraids.com), to use for lashings and bridles, and a yacht drogue by Para Anchor, supplied by Ocean Safety (www.oceansafety.com).

The bucket we used was the ship’s own, bought from a builders’ merchant.

Sail only

This is something most youngsters will have tried out on their dinghy courses, when the instructor whips off the rudder and leaves you to it, but does the theory still apply on yachts two, three or four times the size? To begin with, we thought not.

To balance the sailplan and keep the centre of effort directly above the centre of lateral resistance, Growling Kougar’s owner, Simon Judge, had bent on the No3 jib and tucked a reef into the main – we toyed with a second reef or bending on the No2 for better balance, but opted not to do so.

Our initial attempts at steering the boat using sail alone proved unsuccessful. It was possible to hold her on a straight track using sails alone but the slightest chop or any change in wind direction and strength would have her careering around the compass

We based our first attempt on the principle that trimming on the jib and easing the main would bring her head down, and easing the jib and trimming on the mainsheet would steer her to windward.

We soon realised the importance of trim – using weight to heel the boat one way or another so that the hull’s waterline profile was changed to suit our purpose. Weight to leeward brings the head up, weight to windward brings it down and weight along the centreline keeps her steady

We spent 30 seconds pirouetting from beat to reach to run and back before those childhood lessons came flooding back and we started moving our weight about to trim the boat, to alter her waterline profile to improve directional control. This involved moving weight to leeward to luff up (as you would to ‘roll-tack’ a dinghy in light airs), moving weight to windward to bear away and keeping her on an even keel to maintain a course.

We managed to hold steady courses, though not always the ones we planned. On a heavier cruising yacht, it’s unlikely that an average couple would be able to trim the boat to windward and leeward. Unless you have a very directionally stable long-keeler, this method, while fairly effective, is a non-starter

After five minutes we felt quite well tuned in and we were maintaining courses – not always ones of our choice – but the level of concentration needed to keep her on track would soon become exhausting, so it’s not a choice for long distances in a fin-keeler. A few larger waves would also have made the task more difficult, knocking the boat off course. It’s also worth adding that, on any course below 120° apparent wind angle, the jib is overpowered, and eventually shadowed completely, by the main, so it won’t work downwind.

Jury rudder

This method takes the most obvious approach of replacing the rudder in some temporary way. Generally, this means turning a spinnaker pole into a huge oar by tying a flat panel to the outboard end and using this ersatz oar as a sweep to steer the yacht.

We used mooring line to fasten the board to the pole, but you could use any cordage. We have used hose clips in a previous test. If you don’t have a large enough board, smaller ones can be fastened together. To attach the board, we used a lace lashing on a pre-drilled board, and heavily frapped to make sure the board wouldn’t work loose.

A jury rudder is the most obvious way of dealing with a lost rudder, and it felt like the natural solution. The principles were very familiar and moving the sweep was less arduous than I’d imagined

The pole was attached to the yacht in five ways. First, a safety line, attached to one of the bases of the split backstay, made sure we didn’t lose our contraption over the side. A second pair of lines, each fastened at one end to one of the split backstay tangs, was clove-hitched tightly around the pole, both tied in opposite directions to limit the chance of the pole rotating in its lashings, and then secured on the backstay base opposite. We also rigged a fender to prevent the pole chafing on the transom but this did work loose, so needs more thought. In real life, you’ll have no qualms about using anything from towels to bunk cushions to protect the yacht and the system.

We used opposing clove hitches and a Spanish windlass, as shown, to tighten the lashings. The Spanish windlass is a useful way of tightening your control lines, but be wary. The Royal Navy banned its use after injuries suffered when a windlass unwound

Then we used a winch handle to create a Spanish windlass to tighten these lines on the starboard side. The second pair of lines, from the midships blocks aft to the board, were intended to prevent the board from lifting clear of the water. The working ends were lashed to the pole and run under the board’s leading edge, which tended to turn the pole, but two holes with stopper knots either side would have improved that.

It was surprising how little of the board needed to be immersed to maintain steerage. Changes of direction needed a bit more muscle, but there’s no doubt I overestimated the size of the board required to steer our test yacht. Something half the size would have been just as effective

This method proved remarkably effective. We could sail upwind at 40° apparent wind angle, right down to 150°, and hold our heading easily. It was surprising how little effort was required. To maintain direction, very little of the board needed to be in the water. This significantly reduced the load on the oar and reduced its drag, allowing speeds upwind of 4 knots.

We had so much control that we even threw in a few tacks. This method is fast, effective and there’s plenty of scope to improve it as a steering system

When changing direction, the helmsman, in ‘gondolier’ style, was required to dig the board in and exert a fair amount of force. This and the Spanish windlass gradually unwinding itself caused the pole to turn in its lashings, making steering more difficult.

Two tweaks: (left) Tying the pole to the wheel and using the autopilot could aid steering, and (right) moving the pole with a block and tackle

As well as reducing the size of the board, we identified several tweaks to the system, improving efficiency and reducing chafe in the rig. It was obvious where improvements were needed, but making it work tested our ingenuity!

Drag steering

We were using a drogue as our drag device, tied to a long line, again nylon three-strand. As most yachts won’t carry a drogue, we also tested the ship’s bucket, too. We didn’t have a swivel but we would have included one to prevent the drag device twisting the three-strand line.

Using the bridle

As soon as the bridle pulled up, we had directional stability and a sense of calm descended. Though slow, this method buys you plenty of thinking time

The long line and bridle arm were rigged through midships blocks so we could turn the yacht on her keel.

Using midships blocks means the drogue is turning the yacht about its centre of lateral resistance – the keel. A pole would increase the turning moment

The drogue’s instructions specified 80m (260ft) of line with an extra 15m (50ft) for the bridle, rolling hitched as far down the line as possible. We followed those instructions as far as our resources would allow, with around 150ft of long line and 30ft of bridle.

With the drogue, the effect was remarkable and instant. She would hold any heading, showing great directional stability, and give you plenty of time to balance the sails. Suddenly, for the first time, we had complete control.

In directional terms, the drogue is the best option, but speed upwind was reduced to 1.5 knots at best and even fetching at 50°, we never managed more than 2 knots. This may affect its suitability for longer distances but it’s certainly the most relaxing of the three methods tried.

This stout builder’s bucket proved an adequate substitute for the drogue, in the very short term at least

When we replaced the drogue with a bucket, I was expecting the handle to bend and the bucket to be lost almost instantly. I nearly suggested bracing its mouth open with a wooden batten to prevent its collapse. In the event, it worked well and was retrieved intact. It was some bucket! Sadly, it had no markings so we can’t tell you the brand, but it was a builder’s bucket rather than one bought in a chandler’s.

Making a hole in the bucket, to promote some flow, would reduce the amount of drag. That said, with the bucket intact we were already making 3.5 knots at 50° to the apparent wind – good progress and on a steady heading.

Using the pole

Next, we tried using the spinnaker pole strapped to strong points in the cockpit – secondary winches in this instance – with the long line and bridle arm running through each end.

We tested the pole even though we had perfect control without it. It made little performance difference but reduced chafe

Mounted in this way, the pole had several advantages: it increased the drag device’s performance by creating extra leverage; reduced chafing; and kept the control lines safely out of the cockpit. The only downside was that the secondary winches were no longer available for use.

The drogue manufacturer recommends an 80m tow with the bridle 15m off the stern. We got as close to that as the Solent’s depth and popularity allowed

The primary benefit over the clove hitch is that the rolling hitch grips the line in one direction. The knot above won’t slide to the right

What we learned

Sail and boat trim

Sail and boat trim was the quickest, actually reducing drag, but holding course was very demanding and rarely sustainable

If you have a long keel, or to a lesser extent a long fin, the sail and boat trim method might prove successful in the longer run. If you can get her going in the right direction, it is certainly the quickest method. But if there is a sea running, she’ll be knocked off her heading every 30 seconds and need retrimming. For this reason, it doesn’t seem to be a practical solution to the problem even for long-keelers, and it’s certainly not for fin-keelers unless you find yourself on a plate glass sea with a steady breeze.

Pole and board

The jury rudder method offered a decent combination of speed and control, and also had the most options for customisation

The pole-and-board jury rudder method has the advantage of being intuitively the right answer. In practice, it’s very effective without reducing boat speed too severely. This method is also the easiest to refine and customise to your yacht’s needs and could, given time and thought, become a system almost as easy to manage as the original steering system itself. Like all the systems, it is best used in conjunction with sail and boat trim.

Drag steering

Deploying the drogue switched off the crisis instantly, returning control and calm. It is very slow but for an easy life, it’s the best choice

The drag steering method was far and away the most relaxing, requiring very little input from the crew other than hauling the drogue or bucket from side to side to change direction. The downside was the speed, which rarely exceeded 1.5 knots using the drogue, in 10-12 knots of wind. For longer passages, the time taken to reach safety could cause other problems, such as running out of food and water.

After the test, the general feeling was that, if the rudder carried away, deploying the drogue would allow you to regain control and consider the options available to you, buying you vital time. Once you have perfected your pole-and-board method, take in the drogue and you’ll be sailing three times as fast.

Adapting equipment

In times of crisis, everything on board needs two uses. What would make the best jury rudder? A cabin door, locker door, under-bunk panel or sole section? How about a dinghy oar? Would the teak grate in the cockpit work? If there’s no spinnaker pole, would a boathook and broomstick tied together suffice? Could we use the main boom? If the bucket is broken, what can we use as a drogue – a storm sail? A long bight of warp? What about the spinnaker snuffer?

Once you’ve improvised your solution, wait for a quiet summer day, tie off the tiller and try it out. Make sure you’ve got plenty of anti-chafe material – cushions, fenders and old blankets – to make sure you don’t cause any damage. It will pay to have had a rehearsal.

Rudder loss incidents

2009: Auliana II

Auliana II lost her rudder less than 24 hours after the start of the Atlantic Rally for Cruisers in Las Palmas, Gran Canaria. The crew of the German one-off 53-footer did not report any collision, so there is no explanation of why the loss occurred. After trying and failing to make steerage back to Gran Canaria, skipper Christian Potthoff-Sewing, from Bielefeld, took a tow. However, deck cleats kept pulling out and a tow could not be secured on the deck-stepped mast, so Auliana II was cast off and the crew abandoned her. The yacht was salvaged 11 days later after being located using her GPS tracker. A jury rudder was fitted and the yacht safely made Tenerife.

2009: Star Fire II

This Sadler 25, sailed by Alan Harris and Tom Borsay, was a third of the way into her Atlantic crossing – not with the ARC – when she struck debris and lost her rudder.

Star Fire II had intact cheeks, pintles, gudgeons and a tiller to work with, and used spare shelving to make rudder blades

Under the generous escort of Ray Lawry’s Najad 361 Silver Bear, an ARC yacht, and using some old wooden shelves Alan’s father had insisted they take along, the crew made several jury rudders and completed the last 1,700 miles of the crossing.

2006: Zouk

Despite five days spent trying out various jury steering systems, Zouk was abandoned and scuttled in mid-Atlantic

This Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 43, owned by a French sailing school, was on delivery to Antigua with seven on board. The skipper, Caroline Nicol, reported hearing a crack and then watching the rudder float out from below the transom. For the next five days, the crew tried to improvise steerage to complete the last 650 miles of the voyage, but failed.

A distress call brought the assistance of the tall ship Tenancious, but even this system made by her engineers, failed to save Zouk

After a distress call, Tenacious, the Jubilee Sailing Trust’s 177ft Tall Ship, stood by and assisted, eventually taking Zouk in tow. Despite using their anchor and chain as a drogue, Zouk’s shearing motion chafed through the tow lines and eventually her owner gave the order to abandon ship and scuttle the yacht.

2001: Heya

Heya used two steering guys on a spinnaker pole clipped onto a bathing platform. This simple method took the crew 325 miles to their destination with very few problems

This Swiss yacht lost steerage in strong winds and heavy seas during the 2001 ARC. The crew improvised a rudder by clipping one end of her spinnaker pole to her bathing platform and steering with guys attached to the pole. In this way, they completed the final 325 miles to St Lucia without assistance. However, they did need to reduce sail early or heave-to in stronger winds, suggesting that a larger steering blade would have been more effective.

Emergency steering systems

Self-steering specialists Scanmar and Windpilot both make emergency rudders that deploy on transom fittings to restore complete control.

Scanmar

Scanmar’s SOS Rudder stows in a bag until you need it, then attaches to fittings pre-installed on the transom. The result is a stainless steel rudder, stock and tiller that will see you home

Windpilot

Windpilot’s SOS Rudder Pacific Emergency is for boats already fitted with Pacific self-steering. The SOS Rudder Solo Emergency has its own dedicated transom fittings