We tend to consider paper charts the most reliable means of passage planning, but both electronic and paper options offer different useful features, as Bruce Jacobs explains

It’s blowing a good 30 knots and we are in a maze of rocks and small islands in a 60ft yacht moving at speed.

It’s a cold grey sky, the sea state is short and while the crew are calmly calling out the next rock or obstacle ahead, there is a palpable edge in the air.

We are all aware that we need to get this right or we could soon be just another symbol on a chart.

We are sailing deep in the Bohuslan archipelago off Sweden’s west coast.

Stunningly beautiful but like skiing at speed through trees, thousands of miniature islands form a maze of channels, some passable, some not.

Small stone cairns and painted towers mark the way, but can be hard to see until the last minute.

Add in multiple rocks above and below water and this is very challenging navigation.

We have arrived at a particularly tight spot just as the weather has worsened and our navigation has to be spot on.

A chart is only as accurate as the data upon which it relies. Are your paper and electronic charts up to date?

Things are getting gnarly and all we can see up ahead is white water and crashing seas as the waves are now burying the famously small Scandinavian navigational marks.

It’s time to bug out, rapidly, but with no obvious clear water, which way to turn?

Good navigation is primarily about preparation and that means proper passage planning.

It used to be that all planning and navigation had to be done from paper charts and woe betide a junior skipper if a salty old seadog saw you with an electronic chartplotter.

With technology changing so rapidly however, ignoring electronic navigation aids is no longer realistic.

The question now is not if, but how do we integrate them into our navigation?

There will always be the traditionalists who only use paper charts and others who never do more than move a cursor on a chartplotter and follow the red line.

My own view is that effective passage planning lies somewhere in between, and here I’ll show you why.

How accurate?

Our passage-making masterclasses are run in places such as Iceland, northern Norway and Spitsbergen, where a candidate onboard is as likely to see ‘Last surveyed 1860 – navigate with caution’ on a chart as they are to see a beautifully buoyed channels such as in the Solent.

Indeed the Norwegian Hydrographic Office is reported to have said there may be around 35,000 rocks missing from its charts.

So while the debate may still rage in some quarters as to whether paper or electronic charts are the best medium, one should in fact assume that neither are 100% accurate.

Our skippers use both in their navigation, but more than anything they are trained to get up on deck, assess the situation and have a constantly developing picture in their mind of where they are, what’s happening at any moment and to be planning ahead to understand what’s going to happen over the next hour.

If the situation alters and rapid changes are needed, it could be too late to be starting to plan from either paper or electronic charts.

Keeping charts updated

Accepting that charts can only ever be so accurate when they are printed, they can also rapidly become out of date.

New windfarms, jetties, alterations to a harbour entrance: there is constant change and the challenge is how to keep the charts up to date.

Once a year, we sail from the west coast of Scotland to the Faroes and then on up across the Arctic Circle to Iceland and northern Norway.

The ability to make notes on a paper chart comes in very handy and is something that digital charts have yet to match

Just this one passage requires close to 30 paper charts and it is simply not realistic to look up and make the corrections given by the UK, Danish, Icelandic and Norwegian maritime authorities.

Similarly, you may choose to use the paper charts on your rented yacht in the Greek Islands, but when were they last updated?

It is here that electronic charts come into their own.

Those loaded onto data cards (as for most chartplotters) can be fairly easily updated online or by sending them back to the cartographer.

Meanwhile, mobile sailing apps such as Navionics are even easier as they can be re-downloaded at will, ensuring the latest corrections are seen.

It is by far the most realistic way to have up-to-date charts on board and it would be almost foolhardy nowadays to ignore their benefits.

Planning and evaluation

When assessing a passage, it’s all about the big picture and being able to answer the most basic navigational question of all: is this a sensible passage?

Small-scale paper charts are ideal here as they allow the full picture to be seen in a way that an electronic chart can never do.

Not only does one have a much greater surface area to see at any one time, it is easier for various people to gather round and see the chart and there is a simple physical interaction that undoubtedly helps draw out the key information.

A chartplotter may instantly tell you the distance between two points but it is often only in using one’s Portland plotter and dividers that the hazards en route or the warning text is noticed.

For a skipper needing to build the big picture in their head, while an electronic chart is perfectly useable, we are firm believers that a large paper chart with its breadth of information is hard to beat at this stage.

Detailed route planning

Once you get into the detail, there are pros and cons to both paper and electronic charts.

Electronic vector charts always have the very real danger that hazards such as rocks or overhead cables are not shown until the correct level of zoom is selected.

There are so many incidents of yachts foundering due to this inherent weakness that it cannot be ignored (see below for examples from the Cork Clipper and Vestas Wind incidents).

Safe planning on electronic charts necessitates zooming in to great detail and then scrolling right along one’s route, checking for hazards.

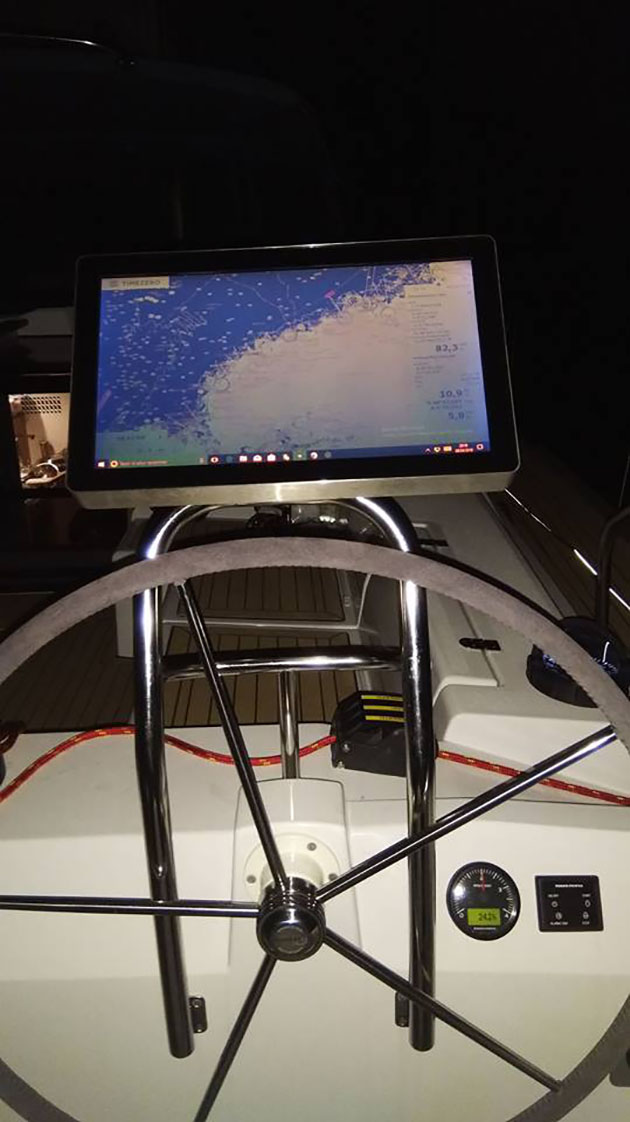

Though much passage planning is still done at the chart table, having a cockpit screen allows easy access on deck

It’s time-consuming and not that practical in coastal waters, especially if there’s a long distance to go.

Paper charts are of course ideal for this, as one can quickly identify the key hazards.

We also like to mark out no-go areas with a pencil to aid our navigation, especially if unexpected changes are needed en-route: something which can’t be done on electronic leisure charts.

The flip side is a much more practical one: is the correct paper chart at the required scale on board?

If so (and it is reasonably up to date) then have worn creases, sharp dividers, pencils, erasers and cups of tea taken their toll?

Who hasn’t found the chart they need missing, or pulled out the right chart only to find it a mess, with key details missing from where countless erasers have done their work?

Such are the safety benefits of not missing a hazard that our expedition skippers ultimately do their planning on paper charts wherever possible but then transfer the plan to the electronic charting system for a double check and for the execution phase, thereby getting the best of both worlds.

Programmes

Recently a number of new passage-planning apps and programmes have launched.

These purport to do your passage planning for you and determine ‘the best time to go’, although the primary output seems to be calculating a course to steer based on the tidal information.

This highlights perfectly the growing clash between the seductive claims of technology and fundamental seamanship.

A big bonus to many modern chartplotters is the ability to include live information such as AIS, radar and tidal data

A passage plan involves so much more than tidal calculations: it involves detailed research from pilot guides into suitability of ports in various weather conditions, back up anchorages, sea state based on tide and historical wind, emergency contact details and more.

Course to steer (CTS), much beloved of RYA theory courses, is barely used in truth as the wind, current, tacks, traffic and timings are always different to the plan and unless one is sailing a considerable distance directly across the tidal streams, a CTS is almost impossible to calculate accurately.

One might choose to aim 20 degrees to starboard to counter a tidal stream, but that would be as detailed as most ever made it.

Electronic passage planning programmes and their claims to do their work for you should be treated with extreme caution and never used in isolation of one’s own planning and assessment of a voyage.

Execution

It is in the execution of the passage that electronic charts come into their own.

Especially if the planning has been done on paper charts and transferred, the navigator can be sure that the route is safe to follow.

We’ve all been brought up with the ‘never bring charts on to deck’ mantra although there are some fantastic perspex holders we use that protect the chart from the elements, and that can be marked on with a wax pencil.

However most yachts these days have a chartplotter in the cockpit and this gives a real-time picture of where the yacht is in relation to the route.

If the yacht has AIS, this picture can also be overlaid with real-time information on commercial (and leisure) traffic including Closest Point of Approach (CPA) and Time to Closest Point of

Approach (TCPA).

Add to that the ability to overlay real-time tide and weather information and there is really no choice to be made.

The argument used to be made that a failure in the GPS system would expose the sailor using electronic charts, but when did the GPS network last fail and in the balance of probabilities of everything that can go wrong at sea, should this be the primary concern?

Beyond chartplotters

Increasingly, even chartplotters are being replaced or supplemented by tablets and phones.

Superb charting apps such as Navionics can be quickly downloaded giving detailed, accurate and up to date charts for very low cost.

With most phones and tablets now having inbuilt GPS, they are quickly becoming a must-have solution to navigation and pilotage.

Increasingly navigation can be done on a standalone tablet or smartphone

Their mobile data also allows real-time weather and tidal information to be downloaded and this combined with position, radar and AIS is an absolute winning combination.

When travelling to more off-the-beaten- track locations, our skippers often also use Google Earth to get a feel for how attractive an anchorage may be or what, if any, facilities and sights a harbour may have.

Not only does this setup give by far the greatest range of information it is also the cheapest.

Apps such as Raymarine’s Raycontrol allow the mirror image of one’s MFD to be seen on a tablet or phone, so even if there is not an MFD in the cockpit, all the essential info can be on hand.

There is simply no going back to paper only.

Looking forward

We are, however, spoilt in the UK with the superb quality of our paper charts.

They are designed to be used without GPS and show key information on land that can be used to take bearings, heights and distances.

In our experience, this is simply not the case with the leisure charts in most other countries.

Land-based information is often negligible and this makes the use of GPS for navigation all but compulsory.

Paper charts are probably not essential anymore, but they are incredibly useful and to our mind a significant safety factor.

A proper MFD on deck is more easily readable than a tablet at night, particularly during the day in bright sunshine

However, with Wi-Fi enabled navigational equipment becoming ever more ubiquitous, battery life increasing rapidly and nearly every electronic device now having in-built GPS, navigation is inevitably moving full speed into the digital age.

The question of whether there will become a time that paper charts are no longer necessary is a difficult one to answer.

On the one hand, it does seem inevitable that at some point in the future there will be sufficient technology and failsafes for that to be the case, but I do not think we are quite there yet.

It is true, however, that there are some circumstances already where seamanlike passage planning and navigation can be done entirely digitally but most of us would still consider a paper chart a sensible backup.

I would argue that this is also true of the reverse.

There are some (and increasingly more) situations where doing everything exclusively on paper is less sensible than using digital tools at your disposal, and keeping a track of your intended route on a digital chartplotter is a sensible plan even if you are planning on using predominantly paper charts.

A final note

Bruce Jacobs is the co-founder of Rubicon 3 Adventure Sailing, specialists in high latitude and off-the-beaten-track sailing expeditions.

Remember: what neither your electronic chart nor paper chart can do is ensure you navigate safely.

A good navigator needs to be on deck, looking at the coastline, monitoring other shipping and keeping a sharp eye on weather, visibility, tide and timings.

Ultimately it is only this sharp observation that allows one to be in tune enough with one’s surroundings to maximise safe navigation.

Back on our passage making masterclass on the Bohuslan coast, our candidates had anticipated this as a pinch point and had pre-planned an escape route.

They had already visually located the island to head for and were able immediately to turn toward it, knowing that the chaotic and fairly scary-looking water had nothing unexpected lurking underneath.

In less than an hour they were safely anchored in the lee of the island, enjoying a well-deserved cup of tea.

That was simply down to good preparation and that can be done on both paper or electronic charts.

Cork Clipper and Vestas Volvo Ocean Race incidents

Volvo 65 Vestas Wind grounded on the Cargados Carajps Shoals

Two significant incidents in recent news have shown the difficulties presented by purely using electronic charts for passage planning and both were the product of the same error.

On 9 November 2014 the 65ft Team Vestas Wind, a competitor in the round-the-world Volvo Ocean Race, was 10 days out from Cape Town heading north towards Abu Dhabi.

She was on a three-sail reach in a true wind of 14-16 knots, 10° aft of the port beam.

Boatspeed was averaging 16 knots with bursts of 21 knots.

Shortly after 1900 she emerged from a rain squall. It was dark, the half moon high in the sky astern was intermittently masked by cloud.

Suddenly there was a sharp crack, a daggerboard had broken.

Rocks were sighted to starboard and immediately an attempt was made to furl the code zero and No. 3 genoa to depower the boat.

The bulb keel, which was canted to port, caught on a rock pinnacle and she swung sharply to port, eventually onto a southeasterly heading, hard aground.

Missing the shallows at the wrong zoom level was certainly a costly mistake

All nine people on board escaped serious injury but she was very badly damaged, high and not quite dry on the Cargados Carajos Shoals, a hazard of which disastrously the skipper, navigator and the rest of the crew had been totally unaware.

The skipper and navigator had discussed the shoals but this was probably based on the zoomed-out chart, from which they deduced that the shallowest water was a seamount over which there might be some change in sea state but which was in no sense a navigational hazard.

The C-Map chart shows only that a larger scale chart is available within the rectangle around the shoal.

Had they consulted the Admiralty small-scale paper chart they carried, or zoomed the C-Map chart in to the same scale, there would have been little chance of missing the significance of the hazard.

In 2010 during the Clipper Around the World Race, the 68ft Cork Clipper grounded on a remote island in Indonesia and was subsequently lost.

A post-race inquiry revealed that the digital chart being used on board Cork Clipper, although up to date, lacked the warnings found on the paper charts for the region.

These warnings indicated that directly transferring latitude-longitude positions derived from GPS to the charts might result in significant error because the chart was not consistent with the WGS84 datum.

Because the digital chart was inconsistent with a GPS-based latitude and longitude, the boat’s electronically plotted position showed the boat safely clear of any obstructions.