Breaking waves and lurking rocks have earned some British tide races a fearsome reputation. Dag Pike explains how to navigate them

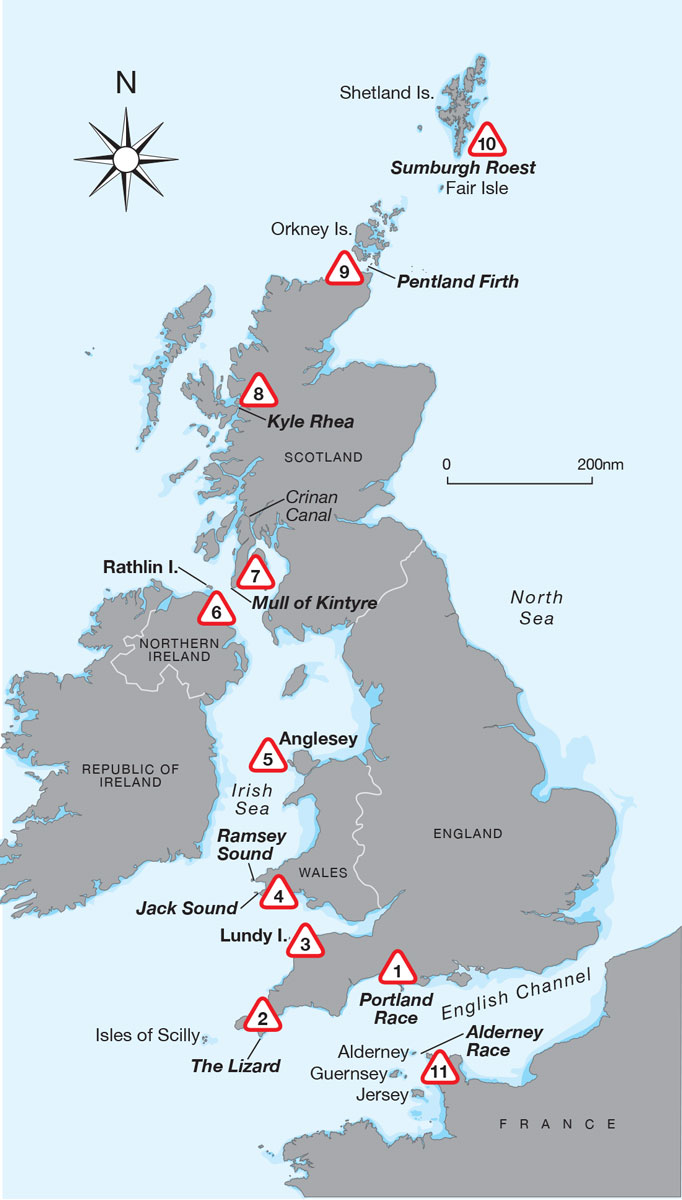

The UK’s 11 fiercest tide races

The British Isles lies in one of the most turbulent maritime regions in the world, writes Dag Pike.

Not only are our shores battered by the depressions that roll in with frequent monotony during the winter months, but every 12 hours the tide turns and billions of litres of water move in and out from our shores.

This huge water flow fills and empties the English Channel, pours up into the Irish Sea and on up and down the West Coast of Scotland and up north it finds a way around the islands to enter the North Sea.

Get your timing wrong through a tide race and it can be an uncomfortable or even dangerous experience. Credit: Graham Snook

The tidal streams generated by this flow can be fearsome, running up to 10 knots in places and when the land gets in the way, impeding the flow of the tide, tide races can generate wild seas that can prove a significant hazard for sailing yachts, with short steep waves, where you can barely recover from one wave before the next one hits you.

In benign conditions this need hardly trouble you.

Where the seabed rises suddenly, tidal flows are concentrated around headlands or through narrows and if the tide and wind are opposed, then swell with a long wavelength in open water will slow down and concertina up, making the waves build in height, with much steeper faces, crests that are much more likely to break and with the ability to swallow boats whole.

You don’t want to get it wrong.

How to tackle fearsome tidal races

Of course the simple answer is to avoid tide races altogether but around our uneven coast, this can be wildly impractical with detours of many miles and hours, or long delays to await better conditions.

Many tide races have earned a fearsome reputation, and not without reason, but once you know and understand them there can often be a way through, either at particular times and states of the tide, in certain conditions, through channels of calmer water, or by enduring a bit of uncomfortable sailing.

You can usually find the areas where tide races occur by reading the pilot guides or they can be marked on the charts so you can prepare for them but a word of caution here.

Don’t follow their guidance blindly.

Firstly, think very carefully about going through a tide race at night.

It can be hard to assess the conditions ahead and often the best route may be close under a headland inshore where you need good visibility to steer a safe course past rocks and lobster pots.

I remember coming up Channel once in the late afternoon in deteriorating weather and thinking about shelter in Portland Harbour.

With an experienced skipper we just made it through the inside passage before it got dark but it was a close run thing.

Secondly, remember that it is not only the sea conditions that can be challenging in a tide race.

The flow of the water increases because the space for the water becomes restricted and the same applies to the wind so you will usually find stronger winds around the headlands and narrow channels where tide races occur.

Then there is the question of selecting the right tide to go through.

Ideally you want to go through a race with a favourable tide so that you speed through, but if the wind is against the tide then you will get much steeper waves and more of them will break and behave unpredictably.

Following winds and tides would be ideal, but if you’re going against the wind, then going through at slack water may be preferable.

In some races, this switch in tidal direction can be quite short lived, maybe an hour at most.

The position of the disturbed water can also change as the tide progresses, so it is no simple calculation.

Remember that while tides are predictable the wind is not, so any carefully made calculations will need reassessing for the actual conditions on the day.

All charts credited to Maxine Heath

You then need to prepare your boat and your crew for what lies ahead.

It may be a calm day but you are about to enter an area of rougher water, so the boat should be set up accordingly.

Having the engine on and ready for action is no bad idea should you need it in a hurry, or to give you an extra shove clear of the worst of the tide.

It may be prudent to put a reef in, in anticipation of the wind increase around a headland, and everything should be battened down and secured for sea just in case.

For the crew it should be lifejackets and lifelines on and restrictions on coming up on deck or heading down below in case one of those unruly waves dumps itself on board.

Tide races can be a test of seamanship, requiring good judgement about how and when to tackle them.

Often the alternative might be many miles added to the distance you have to sail, so it can be easy for your judgement to be biased towards taking the risk.

There can be many factors involved, including the strength of the tides, whether they are springs or neaps, the time of the tides, the wind conditions and forecast, the extent of the tide race area and finally the ability of your yacht and crew to cope with adverse conditions.

TAMING THE BEASTS

I have been through many of the tide races around the British Isles and there is no doubt that an engine gives you a lot of confidence, helps reduce the time you are exposed, and can get you out of difficulties when close in to the shore where the margins for error are small.

Ultimately, with proper planning, a bit of daring, and a seamanlike sense of when to hold back , it’s possible to tame these fearsome tide races, and even use them to your advantage.

1. PORTLAND BILL

You’ll need to aim for seven miles clearance in strong winds to clear the overfallls

Portland Race is one of the most feared areas of tide race around Britain, but it is negotiable.

The area has all the ingredients for disturbed water: a headland that juts several miles out into powerful tidal streams of the Channel, converging tidal streams and a shallow ridge that extends out 1.5 miles from the headland.

Add in a westerly gale and you have turmoil, and this becomes the perfect area into which I used to take new lifeboat designs to test them.

The Portland Race is talked about with reverence amongst seamen and there have been many ships and boats lost there over the years.

OUTER PASSAGE

One of the problems with Portland is that you have to go many miles out to sea to avoid the Race and on a passage to or from the Solent it adds many miles to the journey.

On passage up or down Channel, leave at least three miles offing in good weather, and up to seven miles clearance in strong winds to clear the overfalls, which move significantly throughout each tide.

The inside passage offers an appealing alternative but not one to take lightly.

Eddies form southwards down each side of the Bill, so aim inland of the tip to make the inside passage

INNER PASSAGE

This narrow inside passage can remain passable even when there is turmoil further outside.

It offers a relatively calm route because the tidal flow up and down either side of the Bill bypasses this inshore area and the flow is weak around the tip of the Bill.

Even so you need to plan a passage using this inside passage with care because there is always the risk of getting pushed out into the main body of the race.

The inside passage itself is only about 300m wide, which means you need to pass uncomfortably close to the rocks off the tip of the Bill but there is adequate water quite close in.

If you are heading westbound then the best time for a passage is from -1 to +2 HW Dover, just as the tide turns in your favour, and obviously neap tides are preferable.

Head for a point about 1/3 in from the tip of the Bill as the south flowing tide will carry you south but beware that there is a drying rock about 100m from the shore.

You certainly need to have your engine running. because you may lose the wind under the land if under sail only.

From there you hug the shore line about 150m away and once you have rounded the Bill head up the west side a little way before you bear away across Lyme Bay.

Leave it any later and a back eddy forms on the west side of the Bill that will push you southwards, back towards the race.

Continues below…

Plan your mini sailing adventure – tips for short trips

Dag Pike considers how to get the best out of a summer cruise when time is limited

Heavy weather sailing: preparing for extreme conditions

Alastair Buchan and other expert ocean cruisers explain how best to prepare when you’ve been ‘caught out’ and end up…

‘I was rescued at sea 13 times, but this was the worst experience by far’

Veteran power and sailing yachtsman Dag Pike reflects on his multiple experiences of being saved offshore

TIMING

Coming from the west the timing is +5 to -5 HW Dover and you follow much the same route hugging the shore around the Bill and partially up the east side before bearing away.

These timings are the ideal when the tidal stream is weak but the inside passage is passable at other times in fine weather, but you need extra care to avoid being set south into the Race.

As for the weather, I would hesitate to head round in anything much over Force 4 and you need to avoid wind- against-tide seas with their steep waves.

CONSIDERATIONS

The inside passage is definitely one where you need the engine running so you can maintain full steerage.

It can be an exciting ride being so close inshore and seeing the fearsome breaking waves outside you.

The local fishermen don’t help, laying their lobster pots in the inside channel and you need to keep a sharp lookout because a rope round the propeller is the last thing you want in these challenging waters.

For many South Coast yachtsmen negotiating the inside passage at Portland is literally like a rite of passage and it will certainly give you Brownie points in the yacht club afterwards.

I have done the passage many times, mainly in motor boats and even in race boats running at 80 knots and I have to say the faster you go the better, and all you get are a few bumps along the way.

Under sail the inside passage needs much more consideration and is not to be undertaken lightly.

2. THE LIZARD

Rocks extend half a mile off the headland, so there is no inside passage. Credit: Peter Barritt / Alamy Stock Photo

The Lizard is a challenging headland with above-water rocks offshore for a quarter of a mile and then underwater rocks for the same distance again so there is no chance of an inside passage.

The tide race starts more or less where the rocks stop in fresh winds and moves to the east on the flood and west on the ebb and extends up to five miles offshore on a bad day.

Heading round the Lizard you have to learn to live with the turbulence unless you want to deviate well to the south.

3. LUNDY

LUNDY: Overfalls exist even in moderate winds and on both tides. Credit: Paul White Aerial views / Alamy

Several areas of shallow banks create extensive overfalls

Put an island in the middle of the strong tides of the Bristol Channel and add in a couple of patches of shallow water and you have the perfect recipe for tide races.

They exist both to the north and the south of the island, extending about a mile from each end of the island with further overfalls over the North West Bank and the Stanley Bank, with those on the latter extending more than four miles to the north east.

Tides here run at over four knots on springs so the overfalls will be there even in moderate winds and on both tides.

4. JACK SOUND, RAMSEY SOUND & WILD GOOSE

The aptly named Bitches – a ridge of rocks off Ramsey Island. Credit: Ken Edwards / Alamy Stock Photo

Pembrokeshire sticks out into the Irish Sea and forms a major headland if you are heading north or south in the Western Approaches.

Off the headlands there is a series of islands and the whole area is subject to powerful tides running up to five knots generating a series of tide races that create a challenge to the cruising yachtsman, especially in fresh winds.

The islands run out to the Smalls some 15 miles offshore and span north and south for 10 miles with shallow banks even further north.

All of these interrupt the flow of the tides and this is what generates the various tide races in the area.

Add in a westerly gale coming in from the Atlantic and this is really wild country for sailors.

INNER PASSAGE

It is too far to round all the headlands in one slack tide, so pick where you want the tide under you

The shortest passage around the headlands is via Jack Sound and Ramsey Sound, which are narrow gaps between the inshore islands.

While these are a viable route for yachts, they have their fair share of shallows, rocks and very strong tides. In both sounds it is advisable to make the passage with a favourable tide but this can bring its own problems.

In Jack Sound, the southerly of the two, the clear passage is little more than a cable wide and you need to identify the two rocks that mark the edge of the channel.

These are barely awash at high water and with a potential six-knot tide behind you making it hard to stop, it can be an anxious time until you see the clear way through, particularly when there are breaking waves all the way across the channel.

DON’T BE DISHEARTENED

It sounds worse than it is but as long as you concentrate and keep to the centre all becomes clear in good time and you pop through like a cork out of a bottle.

Obviously slack water is a good time to make the passage but there are not many places where you can wait comfortably for the tide to ease.

Ramsey Sound to the north has a bit more space with the narrowest part at the aptly named Bitches being two cables wide.

The Bitches is a ridge of rocks running out into the channel from Ramsey Island and on strong tides you can see the water running downhill between the rocks.

North of the Bitches is the isolated Horse Rock that is just awash so your course here needs to be biased to the west.

Once clear of the dangers, the tide eases and the isolated rocks are all visible.

OUTSIDE ROUTE

So the passage through Jack and Ramsey Sounds is viable, but if you are concerned then there is a clearer passage to the west of Skomer and Skokholm Islands in the south and the South Bishop lighthouse to the north, but here you can encounter the Wild Goose Race.

Tides still run strongly offshore and there are patches of tide races even three miles offshore so you need to keep an eye on the sea conditions when the tides are running at up to four knots in these waters.

From the South Bishop to the North Bishop the tides can run up to five knots on springs.

Heading north, even when you think you are clear there is the Bais bank with just 8m of water over it at low water, which is enough to create a race around its southern end and to the east.

If you are heading round into Fishguard there is another race of Strumble Head and this is where we did a lot of drogue trials on lifeboats because it was a reliable area of big breaking waves in westerly gales.

In the south there can be patches of tide races right out to the Smalls, some 15 miles offshore, so this whole area is prone to tide races and in a yacht you will not be able to negotiate all of it within one slack water.

I prefer to pass this area with the tide behind me so that I get through quickly, but that does mean you need to concentrate and this is certainly an area for daytime navigation only, prone as it is to lobster pots.

5. ANGLESEY

The Holyhead race extends 1.5m from South Stack lighthouse. Credit: Hartmut Albert / Alamy

With two set of races, no inside passage and a nearby TSS, slack water and daylight is recommended

The northwest corner of Anglesey is notorious for its tide races with the Holyhead race extending about 1.5 miles to seaward of the South Stack lighthouse and a major tide race extending about 2.5 miles north from the Skerries.

Tides here can run at five knots and at the South Stack there is little prospect of any moderation close inshore so a slack-water passage would be a good choice.

There is a passage inside the Skerries with the shoal areas well marked and, with deep water very close inshore, you can find an inside passage.

This is a challenging area for yachts and a daylight passage is recommended.

6. RATHLIN ISLAND

Strong tides and busy shipping channels make Rathlin a tricky prospect. Credit: Nature Picture Library / Alamy

A race extends right across the sound, and all the way out to the traffic separation scheme

The strong tides running in and out of the Irish Sea create some nasty seas around Rathlin Island both inside in Ratlin Sound and outside where the main shipping channels come within 2 miles of the East Lighthouse.

The tide race extends out to these shipping lanes to the north of Rathlin and in the Sound it extends virtually right across.

Combined with tides running at up to 6 knots this is definitely a fine weather and favourable tide area, although once round Lack-Na-Traw, heading west, you should find calmer waters inshore – at least to Ballycastle.

7. MULL OF KINTYRE

Mull’s counter tide might

come in handy to avoid a wind-against-tide scenario. Credit: Mark Fishwick

The Mull of Kintyre forms the east side of the North Channel where the tidal flow into the Irish Sea is squeezed into an 11-mile-wide gap with Rathlin on the other side.

Six miles of this gap is taken up by the traffic separation scheme for the big ships, so that only leaves a two-mile-wide gap when you want to round the Mull.

Most of this gap can be taken up by the tide race that exists off the Mull when the tides run strongly, so when you are southboundyoudonot have a lot of choice but to go through the race.

Northbound you can venture into the shipping lanes if necessary.

TIDES

Heading south, going offshore to avoid the race isn’t an option thanks to the TSS

The tidal stream round the Mull runs at up to five knots on springs and if the wind is against the tide then the race gets quite agitated. It extends to about 1.5 miles offshore and is located mainly to the area south of the lighthouse.

You can get strange tidal flows around the Mull with a contrary tide running up or down the coast close inshore, which is precisely the opposite to the main flow out in the shipping channels.

This counter tide could give you some options and could allow you to avoid a wind- against-tide situation depending on where you plot your course, close inshore or out towards the main shipping channels.

It would be nice to think that there might be a calmer stretch of water close inshore on this headland but I have never found one.

There are some rocks running to about 1 cable just off the tip of the headland but otherwise you can creep close inshore, though you might then pick up fickle winds when they are affected by the high land.

The Mull of Kintyre looks such a straightforward headland to sail round on the chart but for a safe passage in fresh winds it does need a bit of planning.

Of course there is always the option of the Crinan Canal to bypass this race.

8. KYLE RHEA

Narrow channel can be as challenging as rounding an exposed headland. Credit: Aleksandr Faustov / Alamy

Tidal stream, waves and wind are all concentrated into a small area, making it rough at times

Heading north up the Sound of Sleat the land closes in to the narrow confines of Kyle Rhea where the tides run strongly and in any wind from the SW the waves build.

The main tide race here is at the Southern end of Kyle Rhea, particularly on the south-going tide, but heading through the Kyle you not only find very short, steep waves but also strong eddies.

The tides run up to seven knots through here and there can be strong squalls so this is definitely a place where you need the engine on for a safe passage.

9. PENTLAND FIRTH

Conditions in various part of the Firth can be enough to fully submerge a yacht.

Pentland Firth, the passage that lies between the north coast of Scotland and the Orkney Islands, has tidal streams that are amongst the fastest in the world, running at up to 16 knots.

The Firth is the southernmost link between the Atlantic to the west and the North Sea and the tides are generated by the Atlantic trying to fill up and empty the North Sea on every tide.

It presents a challenge for small craft and big ships alike but for the serious cruising yachtsman it is a vital link when heading round Britain.

MULTIPLE RACES

Distances are relatively small, so you should be able to transit the Firth within the hour around slack water

There are a variety of tidal races in the Firth, many of which occur at different states of the tide.

The Merry Men of Mey forms off St John’s point at the western entrance to the Firth on the west-going stream and grows in extent as the strength of the tide increases to reach right across the Firth to Tor Ness in Orkney.

The worst part is over a 24m patch 2.5 miles north of St Johns and this is wild country for any small craft.

I have been through this race in a lifeboat in a westerly gale when the whole boat was submerged at one time so this is not a tide race to take lightly.

The amazing thing is that the Merry Men forms a sort of ‘breakwater’ and it can be relatively calm in the waters to the east of it.

THE SWELKIE

Then there is the Swelkie off the northern end of the island of Stroma.

This island narrows the Firth and the tide race can extend almost right across to the island of Swona and will move east or west depending on the tide and can be particularly violent on springs.

South of Stroma is the Duncansby Race also known as the Boars of Duncansby which reaches across to Duncansby Head on the mainland.

Again this race will move around depending on which way the tide is flowing and it can be particularly violent in stronger winds but there can be a brief lull at the turn of the tide allowing a relatively safe passage.

The Liddel Eddy forms between South Ronaldsay and Muckle Skerry in the east- going stream.

In addition to these more open sea tide races, eddies and even whirlpools are reported around the ends of the various islands in the Firth particularly around the Pentland Skerries to the east so this whole area can be something of a maelstrom particularly during spring tides and in gale force winds.

TIMING

Timing is everything in making a passage through the Firth and obviously around slack water is best.

If you are hugging the land and going through the Inner Sound south of Stroma which is the shortest route then the distance is about six miles which it should be possible to cover in an hour with the engine running.

It could take another hour to get to Dunnet head to get fully clear of the tide races and I have had a great sense of relief when rounding Duncansby Head and getting clear of the race when heading east through the Firth.

Pentland Firth has an evil reputation but it is viable when the wind is no more that Force 4 and preferably on neap tides.

If you take the inshore passage which is the shortest then you will be largely clear of the shipping but the main channel is the one that has the lights marking it so at night this would be the preferred way to go.

10. SUMBURGH ROEST

SUMBURGH ROEST: At six miles wide, one of the most extensive races. Credit: tony mills / Alamy Stock Photo

Heading north, keep east, or if heading west, use the inside passage to avoid the race

The wide channel between Shetland and Fair Isle funnels the water that pours in and out from the Atlantic into the North Sea and this tide race to the south of Sumburgh Head, the southern tip of Shetland, extends some six miles south and runs up to six knots making it one of the most extensive tides races around the British Isles.

The race lies mainly to the west of the headland so coming up from the south it can be avoided by keeping east and if you are cruising around the islands there is an inshore passage around the headland.

11. ALDERNEY RACE

Seen from Cap de la Hague, Alderney Race is visible even in light winds. Credit: Mauritius images GmbH / Alamy

Although not strictly in the UK, the Alderney Race is a right of passage for most British sailors at some point in their lives.

When the flood tide runs east in the English Channel it sweeps through the Channel Islands and then comes up against the French coast that runs north up to Cap de la Hague.

Here the large flow of water is channelled between the Cap and the island of Alderney so it speeds up reaching speeds of close to 10 knots at times, creating the Alderney race.

No wonder this race has a fearsome reputation with the race even being visible in light winds.

When the wind is from the north on the flood tide the breaking seas extend virtually all the way across the seven miles between the land masses.

On the ebb, the tidal flow is reduced and the race is less fearsome but it can still be challenging in southwesterly winds.

ROUTE

The race is worse on the French side, though don’t get caught out by rocks on the west side

The worst of the race is on the French side and it is possible to find a more comfortable passage by keeping to the Alderney side although here you have the Race Rock and the Inner Race Rock 1.3 miles off the coast with 10 metres over them but still capable of generating some localised breaking seas.

This is the preferred route particularly in daylight, passing between the two rocks and with GPS it should be possible to find a safe route and avoid the worst of the race.

This is certainly the best option to avoid the strongest part of the tidal stream on the flood tide but it may not be so advantageous on the ebb when the best route could be tucked in under the French coast.

I have come through the Alderney Race on a small ship in a north westerly gale on the flood tide and it was like a maelstrom, with the foredeck of the ship seemingly underwater the whole time.

Under sail, even in moderate winds it could be challenging and this is certainly a place to have the motor on to help you through, or to avoid altogether in strong wind-over-tide conditions.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

DAG PIKE has spent 65 years at sea on yachts and motor boats, and has made several transatlantic record attempts.

Enjoyed reading the UK’s 11 fiercest tide races

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.