Pontoons

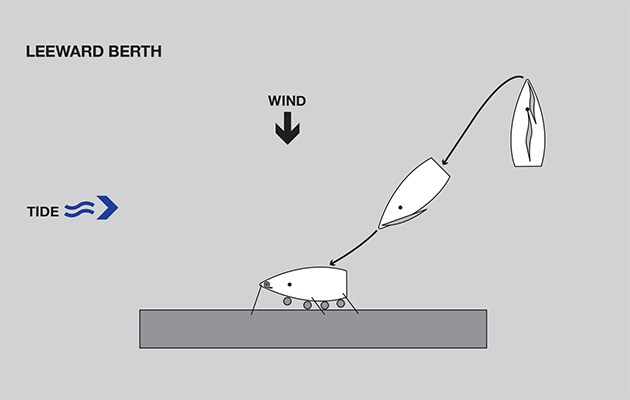

Leeward berth

Sailing to a pontoon gives you more options for fixing your engine, but it takes a confident sailor to sail into a marina and a relaxed marina manager or harbourmaster.

If you are lucky a phone call to the marina will result in a launch being sent out to tow you to a berth, but in the real world you arrive about five minutes after the launch driver has gone off duty.

Tide is king, so approach into it.

Preparation is also key, especially if you are short handed.

Use as many fenders as possible down the topsides.

Use three warps, bow, stern and crucially one from a central cleat or strong point.

A hammerhead is the obvious choice of pontoon, preferably the berth on the end so if you are approaching too fast there is nothing to hit in front.

With no bail-out option, sailing into a finger pontoon isn’t recommended!

1. Drop the main

Having sailed upwind with plenty of space, drop the main before lining up for the approach

If the wind is blowing on to the pontoon (a leeward berth) even only slightly, it pays to drop the main upwind in clear water.

If you don’t, even if the final approach is on a close reach, the boom overhanging the pontoon will be a hazard to any unwitting yachtsmen standing there looking the other way.

There used to be a harbourmaster’s shed on a pontoon at Warsash on the Hamble whose windows were regularly broken by the booms of yachts sailing alongside.

Alternatively the slack mainsheet can wrap around an electrical and water services bollard and extract it like a tooth – that’s also an expensive repair.

2. Control your speed

If the wind is aft of the beam as you approach into the tide, happiness is a furling jib which can be rolled up or unrolled to slow down and speed up.

Sometimes even a flapping jib gives too much windage to stop against the tidal stream and it might be necessary to ease the halyard and drop the jib and sail almost under bare poles.

3. Slow but spritely

Remember that if you are sailing slowly under jib alone on a reach, when you sheet in to speed up, the bow will be pushed to leeward before you accelerate forward, so avoid getting downwind of your destination under jib alone.

It’s hard to come to a precise stop in exactly the right position, so the crew need to step ashore quickly.

4. Surge the lines

Take a turn on a cleat and surge the warp on a shore cleat to brake the yacht.

The midships and stern line are best for this.

Surging the bowline simply brings the bow in with a thump against the pontoon.

We’ve all seen seemingly helpful people on marina pontoon take bow lines and do this.

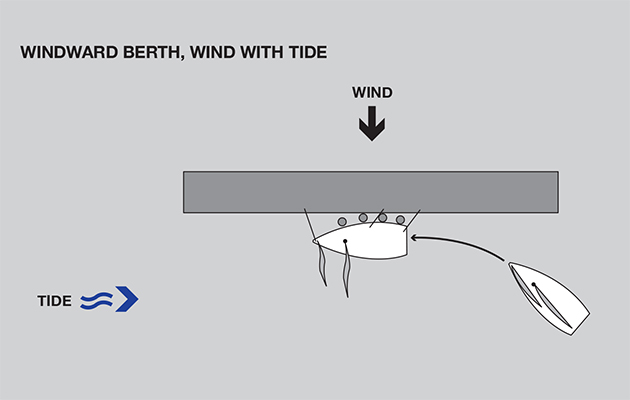

Windward berth

If the wind is blowing off the pontoon –a windward berth – the manoeuvre is harder because you need to keep speed and steerage until the last minute.

You have to approach from an angle to make progress against the wind rather than parallel with the pontoon like a train going down a platform.

1. Close reach

If the wind is forward of the beam, keep the main up, but reduce the size of the jib as you don’t need boat speed, just manoeuvrability.

Approach on a close reach spilling and filling the sails.

How far aft your spreaders are swept, and whether you have a fully battened main, will determine the precise angle at which you can depower.

2. Fine control

On the final approach, sheeting the main in and out through the blocks is too slow if you want to speed up or slow down quickly.

Pull lots of slack through the blocks, and grab the falls in one hand if it’s near the helm.

It lets you add or dump small amounts of power very quickly.

3. Crew position

Make sure you have your fenders low enough. Coming in with any speed will make them swing up and pop out above the pontoon. Make sure you’ve got plenty along the full length of the boat. Credit: Richard Langdon

When you get close you can wind up the jib and ease the main.

The first part of the boat to touch the pontoon will be by the shrouds.

Position the crew there to jump ashore. They need to take a turn fast.

If you’re shorthanded, the midships line will stop the boat and hold you steady, but with more crew the stern line is a better brake.

4. Ready with the bow line

On board it helps everyone if the main halyard is released as soon as a warp is round the cleat – no danger then of the main filling with half the crew ashore and half on board.

The bow will pay off quickly, so you’ll need to be able to reach the bow line from the pontoon once the other lines are secure.

Bring it aft to the shrouds for ease

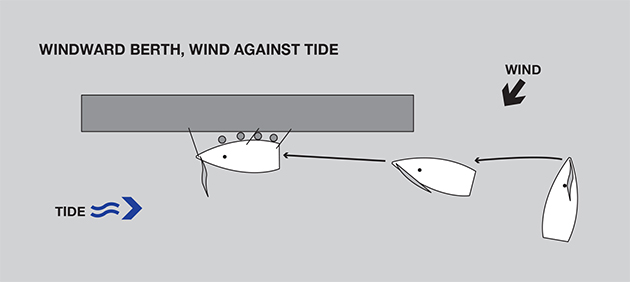

5. Windward berth, wind against tide

If the wind is aft of the beam as you’re sailing against the tide, you need to treat it as a wind against tide approach.

Drop the main as high upwind as you can and come alongside under jib making sure you don’t lose ground to leeward.

In this case you do need to approach parallel to the pontoon.