Mooring buoys

Wind with tide mooring

1. Line up the approach

Judging the tide is critical, and a transit will help with this. Slow your approach by heading up into the wind and current. Credit: Richard Langdon

The principles of this are pretty straightforward and although it’s in the Day Skipper syllabus, it can be a tricky manoeuvre on a boisterous day with a strong tide.

With wind and tide together, use a small jib and a large main.

The approach needs to be on a close reach.

With no tidal stream simply sail to where you think a close reach is, point the boat at the mooring, release the main.

If it flaps and you can pull it in and fill it, you are on track.

From there you can simply fill and spill to adjust speed to the buoy, exactly as you would for a Man Overboard under sail drill.

Of course, in the real world it’s rarely that straightforward.

2. Get the jib right

The jib is big enough to help tacking and assist the windflow over the back of the main but small enough to avoid belting the crew member on the foredeck who is ready with the boathook.

You do need the jib though, as you could end up in irons without it.

3. Start abeam in tide

In a strong tide the starting position could be abeam of the buoy.

The yacht will still be on a close reach but with the boat being set sideways by the tidal stream.

Judging how far upwind and uptide to start is pretty difficult and it’s a skilful helm and a nifty crew who can nail it first time.

4. An eye on the transit

Remember that when the yacht stops next to the buoy it still has speed through the water so keep watching the transit on the buoy as you approach to avoid being set downstream as you slow down.

Just before making contact turn into the wind and furl the headsail completely.

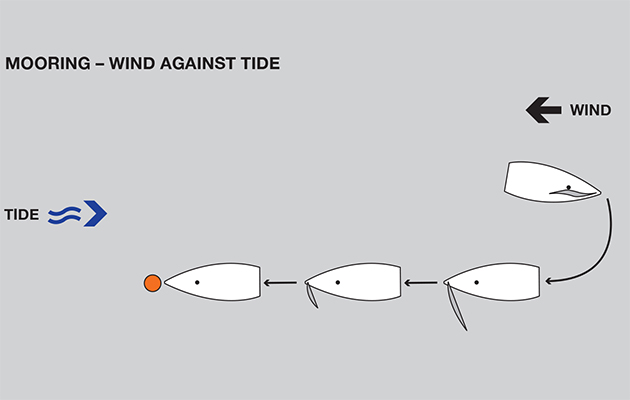

Wind against tide mooring

Approaching a mooring buoy with wind and tide opposed is a piece of cake compared with the wind and tide together, providing you know how to do it.

If you don’t and arrive with the main up it’s going to end messily.

1. Plenty of space

Give yourself a decent distance from which to approach the buoy.

It may be slow, but you’ll look good if you get the buoy on the first attempt.

Simply sail upwind of the mooring, drop the main and sail back against the tide spilling and filling the jib.

2. Slowing down

Depending on the relative strengths of the tide and wind, you may not need very much jib at all to make headway, so furl it away.

If you are still carrying too much way, sheer the boat to one side then the other to show alternate sides of the keel to the tidal stream, which will act as an effective brake.

3. Adding power

If the yacht stops too soon simply apply power with the jib and start moving again.

You can use the halyard or furling line as an accelerator, showing the breeze only as much canvas as you need to make progress and keep control.

4. Stopping with control

You will still be carrying some way through the water, but the boat should be stopped next to the buoy with the sails furled.

This will give you plenty of control as you’ll still have steerage.

The one thing you can’t do easily is to slam the brakes on at this point, except to sheer to either side.

Wind across the tide

What looked like wind-with-tide turned out to be wind-against, and we couldn’t stop as the main filled. Credit: Richard Langdon

Judging wind and tide in the real world is less neat than in the text books, and often you’ll have a combination of wind across tide.

How other boats are lying will give you a good idea though.

It’s important to avoid the main drawing as you arrive, so point the boat directly into the tide and release the main sheet: if it isn’t flapping go down tide of the buoy, drop the main and approach under jib alone.

If the main will flap as you approach the buoy use it in combination with a small jib.